Gaping Ghyll Hole (Part 1)

By Edward Calvert

Very little mention appears to have been made of this “gruesome chasm,” as it has been aptly termed, previous to the early part of this century. One may reasonably suppose that the earliest residents of the neighbourhood knew of it, and possibly that the dwellers in the Victoria and other caves of the district looked upon it with superstitious awe. Then again, the Romans can hardly have failed to notice it, there being distinct evidence of their residence on the neighbouring summit of Ingleborough; and being of a practical turn of mind it may have afforded them a convenient receptacle for prisoners and others who, for political or social reasons, were thought better out of the way. Indeed, it seems not unreasonable to suppose that at even later periods in the country’s history it may have been used as an oubliettes .

What rather surprises one is the meagre legendary history of such a place; it is distinctly the sort of gulf to be guarded by fiery dragons-more fierce too than Scheuchzer’s – and grim enough looking to fit it for the mouth of an “Inferno.” The Rhenish legendaries would have revelled in its possession; and now, after heavy rains, the torrent roaring down, a “thunder of infinite ululations ” reverberating in the immense cavern far below, and the fine spray rising smoke-like from the orifice, it may well strike even the matter-of-fact Englishman with a feeling of awe.

In recent times, on more than one occasion, attempts have been made to measure the depth of Gaping Ghyll Hole, but for the most part the results were vague; in fact, some were actually misleading. On one occasion an enormous length of string was run down without apparently finding any bottom, but this futile attempt to ascertain the depth only confirmed the idea in the natives’ minds that it was in truth a bottomless abyss.

It was not till 1872 that any accurate information was Obtained, when Mr. John Birkbeck, of Settle, made known the depth to be about 360 feet. He then followed this investigation by an attempt to reach the bottom.

As far as can be gathered he saw that the stream, Fell Beck, which flows into the chasm, would prove a source of great inconvenience and danger, and therefore constructed a trench more than a thousand yards long to divert the water along the side of the ravine and over into the adjacent valley. He then descended to what is now known as the ledge, which really forms a bottom to, and is almost directly below, the mouth of the well-known hole, and about 190 feet from the surface. Mr. Birkbeck probably concluded there would be some difficulty in descending below this ledge, as he returned to the surface without having gone lower. This expedition appears to have left the pot-hole still surrounded with a halo of mystery, and there is no record of any other attempt being made up to the year 1895.

During the early part of January ‘in that year I nearly made an involuntary descent of the hole while crossing Ingleborough with a friend in rough weather. The wind had driven quantities of snow across the funnel-shaped opening and almost completely corniced it over, reducing what is usually an opening of some 40 feet across at the top to a hole barely 6 feet in diameter. I am happy to say the cornice did not break through, so we still live to tell the tale. About a year previous to this I had conceived an inclination to investigate the chasm, and having so nearly succeeded without any formulated scheme, my enthusiasm was stimulated, and I proceeded to make my plans and enlist the co-operation of several friends. As is usual in an expedition of this character and magnitude, much time was absorbed in discussion, and owing to the difficulty in settling on a date which would be convenient to every member of the party, the expedition was repeatedly postponed. Alas! fatal procrastination. One morning in August, 1895, the Yorkshire papers announced in large letters that M. E-A. Martel, of Paris, then over on a cave-exploring tour in England and Ireland, had fixed his ladders and descended. We learnt subsequently that M. Martel had been for some time in communication with Mr. J. A. Farrer, of Ingleborough, with a view to attempting the descent, and who had instructed his agent to have the Birkbeck trench repaired ; this practically meant re-cutting it in many places, the still existing indications, however, saving the trouble of .resurveying. M. Martel then arrived at Clapham with his ropes and ladders, and, after allowing the stream to drain for two days, proceeded, with the assistance generously accorded him by Mr. Farrer, to cart his apparatus up to the scene of operations.

The actual details of this historic descent are so well known to all interested in cave exploration that only a brief recapitulation is necessary here. The ladders by which he intended to descend being only 300 feet long he attached a double rope to their top end, which again was made fast to a stout post driven into the ground. This done, he proceeded to descend from the centre of a goodly and awe-stricken crowd of spectators. On reaching the ledge he found the lower portion of his ladders in a heap and had to disentangle and throw them over the edge. He then continued the descent and landed on the floor of the great cavern, the sight of which impressed him greatly. After a brief survey, being wet and cold, he telephoned to be hauled up again, but unfortunately his telephone would not work, and when ultimately he did manage to make those on the surface understand his wishes they concluded he was in a hurry to come up, and so unduly exerted themselves on the rope to which he was tied. To quote from his beautiful book, “Irlande et Cavernes Anglaises,” he says, “I had barely time to grasp the rungs as I passed them.” Twenty-three minutes were occupied in descending; he remained 11/4 hours below and was 28 minutes in ascending. During his visit to the lower regions he made a rough survey of the cavern, which, he says, “ranks among the most impressive that I ever expected to come across in my underground wanderings.” Thus ended the first successful attempt to descend Gaping Ghyll Hole, and M. Martel may well feel proud of his achievement. The descent of 300 feet of rope ladder can only be appreciated by those who have attempted it, and to do so with the knowledge that probably-indeed, I have since heard it asserted-none of his assistants would venture after him in the event of an accident, could hardly be calculated on as a moral support to the explorer.

To have a ripe plum taken out of your mouth just when you are going to put your teeth into it is not pleasant, and it is a pity we were not acquainted with M. Martel’s intentions, as he assures me he would have been pleased to have had our company had he known we were contemplating a descent. It is scarcely necessary to add we should have been delighted to have joined him.

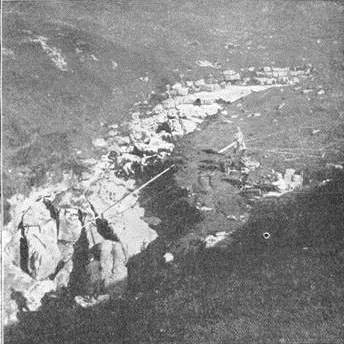

Spurred on by M. Martel’s success, Messrs. Bellhouse, Booth, Gray, Green, Lund, Thompson, and myself arrived at Clapham on September the 14th, 1895, with a considerable quantity of tackle, and proceeded to the mouth of the chasm. The tackle was carted up by way of Clapdale Farm, which, though perhaps the best way, can by no stretch of the imagination he called a road, as, when going over one particularly steep piece of moorland, the cart traces having broken the tackle was instantly shot out and deposited at the bottom of the slope. Little incidents such as this retarded the transport, and darkness set in before anything could be done that day.

On the following day half the party made a dam some distance up the beck to divert the water into the trench previously mentioned, the other half fixed planks, pulleys, and other necessary gear over the mouth of the hole; a windlass was placed a few yards away, and, when the parties had finished their respective work and partaken of a good lunch, I attached myself to the safety line and prepared for the descent. In spite of much damming a considerable quantity of water that joined the main stream from a tributary stream below the dam could not he diverted; this, together with some leakage from the now damaged trench, was still flowing down the beck into the hole, and my descent unfortunately had to be made in the shower bath this formed. In due course I reached the ledge on which Mr. Birkbeck first stood, and where M. Martel found his ladders entangled. Here I spent a few minutes in examining the surroundings.

Standing on this ledge I saw there was a huge rift in the side of the main shaft, connecting it with another and still larger shaft. I could see up this latter into inky blackness, behind an immense rock curtain which apparently divided the two shafts, and below, in the dim light which only faintly penetrated the darkness there, the larger shaft was continued to a great depth. Having observed this l again signalled, and was lowered over the edge of the ledge. The rope now began to sway against rocks which appeared dangerously loose, and after several attempts to keep it clear of them I concluded tackle would have to be fixed at the ledge to avoid the danger of a running rope dislodging and sending down rocks on the head of the explorer. As time would not allow us to make this provision I signalled to he drawn up, and being cold and wet to the skin was heartily glad to reach the surface again. Mr. Booth then made an excursion to the ledge, and after his return we packed up our tackle and went back to Clapham disappointed, but having gained valuable experience and being more determined to make another attempt at an early date.

In the “Memoirs of the Geological Survey,” [1] attention is called to a small lateral passage near the mouth of the main hole, leading to the top of a vertical drop of about 350 feet. It is satisfactory to note that the Surveyors must have given the place much more than a passing glance, as the entrance to this passage is not at all easy to find; yet it played an important part in subsequent events.

The passage, which is entered by crawling under an immense block of limestone [2] a few yards from the mouth of Gaping Ghyll Hole, on the right bank of the stream, is, roughly, 5 feet high by 3 feet wide, but gets smaller towards the inner end, and at about 15 feet along it terminates abruptly over a shaft about 6 feet in diameter with the tremendous drop mentioned.

It occurred to me that if it were possible to fix tackle at the end of this passage, and descend by the shaft there, the difficulties at the ledge down the main hole would be avoided. I therefore descended this shaft some distance on a rope ladder, and satisfied myself that the drop of 350 feet or so was apparently direct, and clear of such obstructions as ledges or projecting rocks.

It was evident, then, that if ropes could be guided from outside into the passage so as to work clear of all rocks, this way would be much more expeditious and altogether safer, by which to make the descent, than the other.

On May the 9th, 1896, as the weather had become reasonably dry, our party again went to Clapham, this time with more tackle. I sent up a number of lengths of large galvanised tubes for conveying the beck water past the damaged portions of the old trench in case we should have to make use of that again; but the advantage of our new route rendered this unnecessary, as the small quantity of water which ran into the passage was easily diverted down the main hole, and no matter how much water ran there we could be very little inconvenienced by it.

Considerable time was required to fix our gear, as, owing to the confined nature of the passage, only three men were able to work inside it at a time. The windlass was placed much in the same position as before, pulleys being set at suitable places and angles to guide the ropes under the stone block previously mentioned, at the entrance to the passage.

The tackle consisted of a main rope, which passed from the windlass under the stone block, then along the passage and over a pulley carried on a timber structure erected over the intended line of descent. At the end of the rope was a boatswain’s chair, on which the explorer was to sit. From this chair another rope, with its twist opposed to the first, hung down to the bottom of the hole, its effect being to diminish the tendency of the seat either to swing or gyrate. A separate rope, tied round the explorer’s body, was held by several men, so that in the event of an accident to the main rope (to which he was also attached) or gear, he would still be held by the safety rope. This was paid out round a stout post, the explorer being thus almost directly in touch with those having control of it. Signals were given during the early part of the descent by firing a revolver, but a telephone was lowered after the first man had reached the bottom, and afforded a much more perfect means of communication.

Having completed preliminaries, I put on the oilskins, safety-line, belt, etc., and, seating myself on the boatswain’s chair, a signal was given to the men at the windlass outside to “Lower slowly!” and down I was lowered.

The sensation at the commencement of the descent was distinctly novel and exhilarating. The weirdness of the faint flickering light from the lamp above soon gave place to a magnificent black-and-white effect, as the sides of the main hole, contrasting dazzlingly with the dark shaft I was in, became visible behind the jagged bottom edge of the rock curtain dividing the two. In a very short time I was conscious of the sound of falling water, and then further meditations were abruptly stopped by my being immersed in a shower bath, which I had just time to perceive was poured from an underground passage in the shaft side. After this sudden shock, however, I soon gathered my wits together, and looking down could see, far below, the ledge on which Mr. Birkbeck had stood, with water streaming over its edge into the darkness below.

I was by this time descending more rapidly, and, the ledge being passed, the sides of the shaft down which I had come, and which until now had been comparatively near, disappeared completely, leaving me feeling somewhat like a spider hanging from the inside of the dome of a large cathedral. The surroundings were so immense that it was some little time before I could distinguish anything at all. Again my meditations were abruptly cut short, for I found myself plumped down on a bed of loose, rounded boulders at the bottom of eighteen inches of water. As soon as I had managed to get clear of the shower bath which had persistently deluged me since I entered it, I gave a cheer (which, however, could not be heard above), for the second descent of Gaping Ghyll Hole was accomplished.

Having signalled for my friends above to “Stop lowering ! ” I disconnected myself from the ropes. Unfortunately, the lamp, which was slung from my chair, having been broken by its sudden contact with the boulders at the bottom, I was unable to wander far from the beam of daylight which dimly illuminated a portion of the floor.

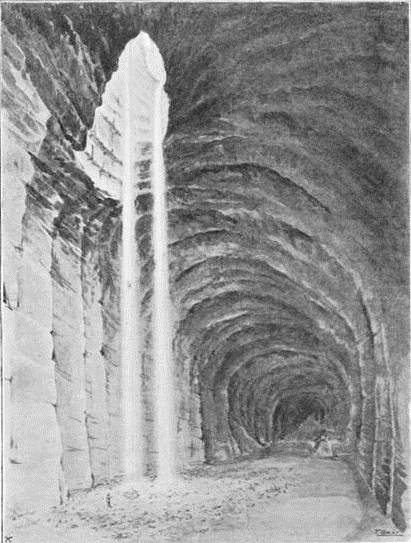

Looking upward, a bright spot of sky was visible through one corner of the main hole, which from here looked almost like white marble. Below the ledge the whiteness ceased, as the darker surfaces of the cavern roof and walls reflected little or none of the faint light falling from above. The full height of the waterfall from the ledge to the floor was visible, but my attention was more engrossed by the other waterfall – the one in which I had descended. The beam of light struck this at about the level of the ledge, and I could see the column of water descending out of the darkness far away overhead. Down the sides of the dark shaft water streamed and splashed over broken rock ledges. The sight of all this – the “swish” of the water through the air, the roar as it fell among the boulders in the pool beneath, and the reverberation of the noise in the cavern, were unlike anything I had ever experienced before, and were most impressive.

It now being late in the afternoon, I once more put on the safety line, sat on the chair, and again entering my shower bath – the highest known waterfall in England – signalled to be drawn up, and was soon at the surface again. My descent had been timed, and though it appeared long in the making, it was accomplished in the short period of two minutes. The ascent occupied only four minutes.

The evident safety and rapidity of the descent and ascent were highly gratifying to me, and the advantage of our method and line of descent over the arduous labour of rope-ladder work and the risks of the main hole, were now clearly demonstrated where a large exploring party are concerned. Thus ended the second descent to the cavern, and our party returned to Clapham for the night.

In my next paper I shall describe the cavern, and give an account of subsequent descents, when our party discovered and explored the wonderful passages leading out of the ends of the cavern.