Gaping Ghyll Hole (Part 2)

By Edward Calvert

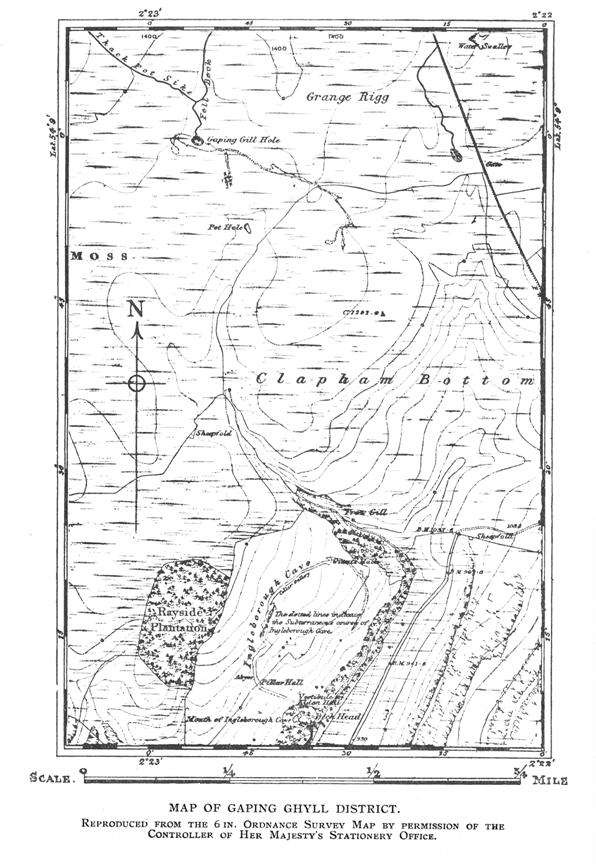

IN the last number of the Journal I related briefly the history of the first and second descents of Gaping Ghyll, and concluded by expressing the feeling of satisfaction among our party at the success which had at length attended our efforts, and which fully compensated for our being, even for us, late to dinner at Clapham on that day. We were astir early on the following morning, but as there were many odds and ends to be gathered together and taken with us it was 7.30 when we reached the pot-hole, and a few minor alterations in the construction of the head gear causing still further delay the morning was well advanced before I was ready to descend.

On again being lowered to the floor of the cavern I took off my oilskin garments and signalled for them to be drawn up for the use of Gray, who was to follow me, as our stock of these articles was limited. This done I was left waiting patiently for the arrival of that – now to me – very important item, the telephone; standing alone in the enormous, gloomy vault, listening to the roar of the waterfall, and practically cut off from all communication with my friends overhead, the instrument seemed to me a very long time in coming. To protect the telephone wire from damage during the passage of the party and apparatus up and down the line of descent it had been decided to lower it down the main shaft, and in the waterfall dropping through it I ultimately descried the wire descending in a very tangled condition. I now regretted the premature discarding of my oilskins, but realising the vanity of regret rushed into the falling water and dragged out the bundle. Unfortunately the instrument would not work, and not until a further supply of wire had been lowered could communication be effected. This had one unexpected result. It appears a number of the spectators, who had by this time arrived, were extremely sceptical of the descent having been again accomplished. Indeed, some of them went so far as to suggest the retirement behind the boulder was made for the purpose of “bluffing” them and consuming the apparently ample supply of refreshments provided. But the visible sign of the telephone wire, and the voice of the invisible man at the other end of it, convinced them that the bottom of Gaping Ghyll had indeed been again reached. Gray then descended and together we walked round the gigantic hall to get a general impression of our surroundings.

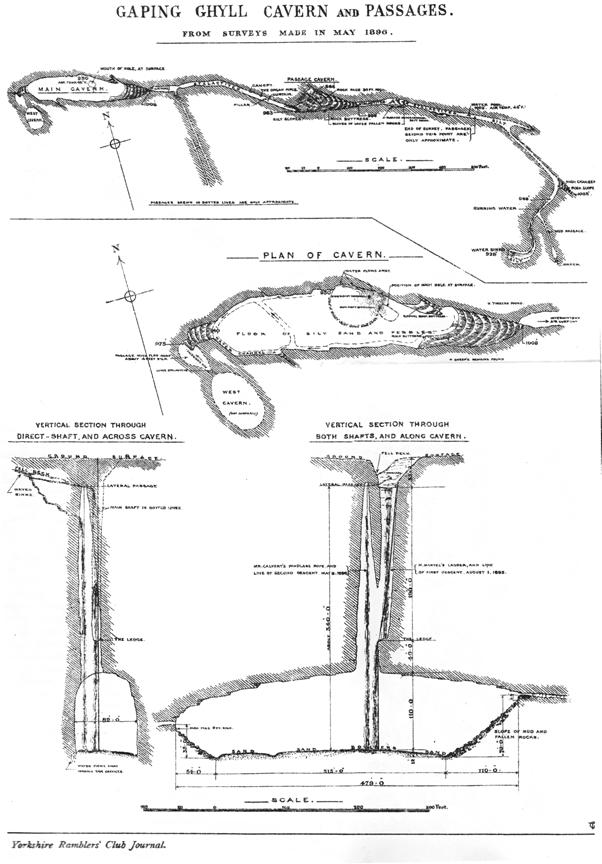

As previously mentioned, the floor immediately under and around the waterfall is formed of smooth boulders, their boundary roughly indicating the limit of the faint daylight penetrating from above. Beyond, the floor is mainly composed of sand and mud, slightly higher in the middle than at the sides, but upon the whole astonishingly level and dry. Across the ends were shallow channels which appeared to be old water courses. Another deep one crossed the floor, and a strong current of water had evidently flowed along it and the side channels to a cleft in the South Wall, about one-fourth of the cavern’s length from the west end. The cleavage of the rock walls – almost uniformly magnetic N. and S. – is very striking, fractures giving a ribbed effect to the sides, and leaving in some places fissures several feet in Width, running 30 or 40 feet into the rock. Through some of these fissures near the shafts the Water found exits, although a great deal of it seemed to flow away beneath the boulders. The roof was so far above us, and so black in the general dimness that we could scarcely discern it, except in the close vicinity of the daylight. Attempts were afterwards made to photograph the cavern, but without success. There were apparently no stalactites. The most notable features are the enormous slopes of debris at either end. That at the eastern end is nearly 70 feet high, and composed of unstable blocks of stone of all sizes. Some fifty feet up the slope were a few baulks of timber and a fence stake, which may possibly have been those thrown down the hole by Prof. Hughes in 1872. At another part of this slope, at least 15 feet above the cavern floor, sheep’s bones and wool were found. These indications seem to prove that in times of very heavy floods the cavern becomes an underground lake – a lake large enough and deep enough to float one of our greatest ironclads.

Our attention was suddenly arrested by shouting overhead, and on looking up we saw what appeared to be a hardware store slowly revolving and descending through space. This proved to be another member of the party hung about with a few of the necessary implements for exploring and surveying. Others descended in turn and the exploration was begun in earnest.

The party now consisted of Gray, Booth, Cuttriss, Green and the writer, and we divided into two sections. Gray and Cuttriss took the survey in hand, and the others started to make a more careful and systematic exploration. The triangulation of the cavern proved it to be nearly 480 feet long, 82 feet at its widest part, and about 110 feet high from floor to roof. Its size may, perhaps, be more strikingly realised by comparing it with some well-known public building. For example, it is three times as long, some 10 feet wider, and 10 times as high as the Victoria Hall, in Leeds Town Hall. M. Martel suggested the removal of the debris from the slopes might reveal passages, but probably sufficient has been written to show how impossible their removal by a party of explorers would be.

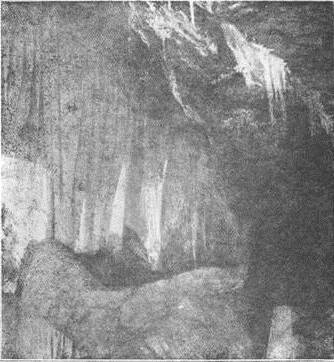

With little hope of finding an exit I carefully led the way up the dangerously loose eastern slope. A few feet above it I discovered a narrow horizontal slit in the rock wall. Calling upon the party to follow with more lights, I crawled through the opening. Progression was not without difficulty, for as the passage widened it became lower, until little more than 12 inches separated floor from roof. Creeping over alternate patches of silt and travertin for a short distance, a white glistening forest of stalactiles and slalagmites was revealed to view. Unfortunately many were broken in forcing a way through them. Then a descending floor allowed me to resume an upright position, and the right side of the passage disappeared amongst huge blocks of stone. Here Booth and Gray joined me and we decided to follow the opening thus disclosed, leaving the shallow and higher main passage for later exploration. Climbing became necessary as the walls contracted and the roof receded, and as we descended backs and knees played important parts in our progress. Leaving Gray within hailing distance of our previous line of advance we went forward another 50 yards, Booth leading. Booth advanced alone 100 yards further and found another parallel passage, but lack of candles compelled him to return. The air in the passages was quite fresh, and with practically no current. In the cave it was very different, and gusts of wind were distinctly felt at the extreme ends. During the progress of the exploration Moore descended. There still remained much to do, but time did not permit us to accomplish more, and we began the ascent to the surface.

While this was proceeding Booth and Gray ascended the debris slope at the western end and discovered another similar outlet, which led into a large chamber. This chamber is still unexplored. In due course we all arrived safely at the surface, thoroughly tired but very pleased with the day’s work.

At Whitsuntide a larger party[1] assembled at Clapham to continue the exploration. Our previous experience enabled us to judge better what would be required in the way of tackle to complete the work, and the things deemed needful made quite a formidable array. The appliances for making the descent were fixed exactly as before. Having descended, three of us proceeded at once along the passage I had so fortunately noticed on our previous visit, in quest of fresh discoveries. The preliminary grovelling over, we were able to walk upright for some distance, the height of the passage varying from 10 to 60 feet. Wonderful natural formations were met with. Innumerable stalactites hung from the roof; one of them, hanging across the passage like a daintily-shaded pink drapery, was the most perfect stalactite formation we had ever seen. One group had a striking resemblance to the pipes of an organ.

Examining all possible outlets we came at length to a strangely weird opening which appeared by the light of a couple of lamps to be the end of all things. Nothing could be seen above or below. The side on our left seemed to vanish into space; the other appeared too steep to be practicable, but on more careful inspection a route was found which led behind some large rocks and brought us nearer the centre of the vast gloomy cavity, the blackness and size of which were made only the more impressive by the flickering light from our two lamps. Burning magnesium revealed a chasm divided roughly into two parts by a great ridge of mud or silt. Carefully crawling further along the slope on which we were I slid down and with a jump landed on the ridge, and was soon followed by Booth. Together we discussed what our next move should be.

The bottom of the chasm appeared to be a considerable depth below the ridge we were on, so Ellet returned to the main cavern for 400 feet of rope, a length of rope-ladder, candles and sundries. Booth and I sat and smoked, trying occasionally to pierce the darkness beneath us with the magnesium light. An aneroid showed our position to be only 20 feet above the bottom of Gaping Ghyll Hole, so we had evidently descended since we entered the passage. As the entrance to Clapham Cave is on a lower level our hopes that we were on the right track were increased. It was an hour-and-a-half before we saw Ellet again, but how he and Firth, who came with him, managed to bring their burden over such obstacles in the time is a mystery. A 400-feet coil of rope is no light or pleasant burden to drag or push in dark passages with little over a foot of head-room, but when stalactites abound to catch every stray coil of rope and to bang your head against the difficulties are greatly aggravated.

We now proceeded to tie the 100-feet rope to the large rocks above, there being nothing on the mud ridge firm enough for that purpose. The rope ladder, fastened to one end of the 400-feet rope, was then lowered down the slope, and I followed tied to the other end of the long rope, the middle of which was fixed to the shorter one. An ice-axe proved very useful here, as the mud, roughly at an angle of 50° (by clinometer), was too slippery to afford safe foothold. About 50 feet down there was a vertical drop of 30 feet; the descent of this with a flare lamp was distinctly awkward, and I landed, more or less singed, on a short steep slope of silt similar to the one above, and from whence it had probably slipped. From here I easily reached the bottom of the chamber. There was no possible outlet from it, so when Booth joined me we turned our attention to the opposite side of the cavern, which we now made out to be approximately triangular in shape. A great slope of stone faced us. It was 130 feet high, and in even greater confusion and infinitely more unstable than the end slopes in the main cavern. Up it we climbed, and at the top found Water trickling from the roof, and numerous small round pebbles, apparently water worn. Some were of millstone grit, but all were covered with a black peaty deposit. Beyond, there was a passage similar to the one we had left on the other side of the chasm, but at a somewhat higher level. Along this were several small pot-holes. At the bottom of these were indications of a parallel passage 20 or 30 feet below, but unexplorable by reason of the dangerously unstable state of the large angular rocky debris. In such a place the unwary explorer, made prisoner by any movement of this debris, would be in an exceedingly awkward position. Broken masses of a conglomerate of silt and carbonate of lime bore evidence of some powerful disturbing force having been at work, though how long ago it would be difficult to estimate. Time passed quickly amidst these interesting surroundings, but fearing our friends might have become alarmed by our long absence, we retraced our steps to the mud chamber. The party then returned to the main cavern and were lifted to the surface again.

On the following day we continued the exploration beyond our previous furthest point, surveying as we went, and lunched by the side of a pool in the now draughty passage. Innumerable small stalactites hung from its roof, which was somewhat too low for comfort. Not that one expects much comfort in a cave. The best of caves have a damp feeling, the air has a peculiar cavey odour, and everything has a sense of age about it. A bivouac on a mountain side is a comparative luxury; it is always fresh, and, at any rate, is washed occasionally with clean water. After our slight lunch of sandwiches, not entirely free from cave earth, we concluded that exploration was of more importance than accurate survey and its necessary delay, so we hurried forward. Twice the gallery appeared to come to an end, but on carefully investigating the sides we each time found an outlet, and crawled through it. Presently the sound of running water greeted us, and on reaching it the passage to our great relief became high enough to stand in with comfort. At this point it was not unlike the cellar gallery in Clapham Cave. Greatly excited we rushed forward, descending small waterfalls, rocky pitches, and other obstacles in splendid style. We began to discuss the best means of breaking through the iron gates at the cave entrance, and pictured the surprise of our friends at Gaping Ghyll when we rejoined them

via Trow Gill. The passage became more and more like the outlet at Clapham Cave, but, alas, below a slope, there was a rapid descent and the water disappeared, some of it through a small crevice, the rest percolating through a large bed of silt. We looked high, we looked low, we wriggled through almost impossible openings, but all to no purpose, and at last we could no longer disguise the fact from ourselves that here the passage ended for us. Sadly we retraced our steps, hoping for a time that one of the small branches passed in our previous haste might have a more satisfactory ending. We explored them all in vain, and finally had to acknowledge that Clapham Cave entrance gates had still some time to stand ere they were broken down from the inside by ruthless explorers from Gaping Ghyll.

Thus ended one of the most enjoyable, impressive, and on the whole successful of our cave explorations, and it is certain none of those connected with the expedition will ever forget it. Great praise is due to all who took part in the work, particularly those who laboured like slaves at the windlass and ropes on the surface, and to Mr. Gray and Mr. Cuttriss for their careful survey of the cavern and parts of the passages.

The passage described in this article was thoroughly explored and, though in itself interesting, has no outlet. The branch passage leading to the south from near the outlet at the end of the main chamber may open out further along, but the absence of any current of air does not encourage the supposition. Still, the furthest explored part of Clapham Cave has a very similar aspect, without the silt, so there remains the possibility.

The outlet at the west end of the main chamber turns in the desired direction soon after its commencement. Underground passages, however, twist and turn about in such unexpected ways that nothing short of actual exploration can be relied upon.

These expeditions prove that if it be possible to pass from Gaping Ghyll to the upper end of Clapham Cave the way is difficult to find and difficult to follow. Even the first stage of the route, i.e., the descent to the great cavern, cannot be undertaken lightly; it will always be necessary to study the probable condition of the weather during the expedition. Telephonic communication with those below, and that or other means of communicating with the actual explorers are imperative. A depot for stores and provisions should be arranged in the main chamber. At least two men should be left there, ready to assist in the conveyance of any apparatus the advance party may from time to time require. They would also prove a valuable source of additional strength in the event of accident. The assistants could be changed, the party above taking their turn at this part of the work. A fire should be kept burning both above and below so that hot food might be available. The advance party, consisting of not less than three, or more than five, should always pay out a line of coarse string as they go, to obviate the danger of losing the way on their return. A good supply of provisions and illuminants should be carried, but their movements should not be hampered by a lot of tackle. Thus, if any serious difficulty should be met with, a plan of action could be the more quickly carried out. Accurate surveys could be made either by another detachment or after the exploration had been completed.