Obituary

Jack Ratcliffe

(Member 1962 – ’75 & 1977 – ’88)

Jack was a likeable character who was very easy to get on with. He will be best remembered, perhaps, as a good companion on the hills and also as a good friend of his fellow teacher, our one-time hut warden, Denis Driscoll. Together they built the Lakeland stone fireplace at Low Hall Garth and the floors in the washroom areas.

He died suddenly on the 1st December 1994 at the age of 82 while collecting logs and loading them into his camper van in preparation for constructing a rustic garden seat. His wife relates that he left home earlier and looked the happiest man on Earth. A man who always kept busy despite the warning of a slight heart attack while playing bowls; he played on to the end of the game.

Jack enjoyed walking, fishing, stone walling, woodworking and making walking sticks from carefully selected wood collected on walks. He loved the Lakeland hills and indeed mountains in general. He married Lillian, at the age of 76, after the death of his first wife. Together they fulfilled his long standing ambition of visiting New Zealand and walking the Routeburn Track. Jack climbed alone up to the summit of Conical Hill. They again visited New Zealand in 1993 but a back pain denied him further exploration of the hills.

Lillian very much enjoyed being introduced to the hills by Jack. He took her to some frightening places but left her with wonderful memories. He is survived by his wife, son and daughter, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. His son and grandson are both climbers. Many of his contemporaries will, like me, have happy memories of Jack.

F.D.Smith

March 1995

A. David M. Cox

(1913 – 1994)

In 1949, the first tutorial I ever had at Oxford was with David Cox. When I went to his rooms I found the walls were hung with photographs of Himalayan mountains. I had already become interested in mountains and I can remember gazing about in admiration, my essay forgotten. I noticed that his bookcases had rows of Alpine Club and Climbers’ Club journals, along side the professional historian’s usual journals. I asked (stupidly) did he climb? So this first tutorial started rather late as he seemed more interested in what I had done, than telling me what he had done. I was to discover that this was the hallmark of David Cox. He had a way of making young people valued, admiring your achievements and rarely mentioning his own feats.

He was born in Plymouth and began to climb as a boy on the Dartmoor Tors. He went up to Oxford in 1932 and by Easter 1934 he was good enough to do Longland’s Climb on Clogwyn Du’r Arddu. That summer he went to the Alps and climbed Pointe Albert and Aiguille de I’M. In autumn 1934, Robin Hodgkin (later the Headmaster of Abbotsholme) arrived in Oxford and they became climbing companions. In 1936 they climbed Climbers’ Club Direct Climb on Dewerstone in Devon. In June 1937 Hodgkin and he camped under Clogwyn Du’r Arddu with the daughters of George Mallory, Clare and Berridge. They made several significant new variations on that crag and at the end of the week, he led the first ascent of Sunset Crack. In July 1938, he made the first ascent, solo, of two routes described as ‘delicate and difficult’, in the Amphitheatre of Craig yr Ysfa. He called the first route Sodom – ‘because there was no looking back’ – but the guide book editors regarded that name as too strong. Its name was changed to Spiral Route. A pity, because the second is still called Gomorrah. After the war he wrote the guide book for Craig yr Ysfa.

We were talking one day about the pre-war climbers. Yes, David knew many of them. He remained quiet, and moved his pipe from one side of his mouth to the other, a gesture I knew he used, if he did not wish to be drawn. I pressed to ask him more. David then went on to indicate that he thought some of them were a little too boastful. One day some luminary was boasting about climbing Lot’s Groove, a Colin Kirkus VS on Glyder Fach. ‘He said it could only be done in rubbers; so next day we went and did it in boots.’

During the war, he joined the Royal Artillery. When the War Office was looking for mountaineers to teach commandos, David was transferred to the Mountain Warfare School then run by John Hunt, arid spent the rest of the war as an Instructor. He taught rock climbing to soldiers in the Middle East on the Golan Heights and in Canada. Towards the end of the war, he was back instructing in Wales. It was during that time he produced another breath-taking first ascent, Sheaf Climb on the west buttress of Clogwyn. In 1986 he was interviewed by ‘High’ about that first ascent. He described how his companion on the climb had injured himself, light was fading, and things were getting desperate. He knew he had to find a way up the last pitches. For once David sounded like Whillans. In 1957 he used a period of sabbatical leave to go to the Himalayas with Wilfred Noyce. They climbed to within 15G feet of the sacred summit of Machapuchare, (6997m), near Annapurna. Noyce wrote later: ‘At this point, two respectably married men decided they should leave the mountain to her stormy privacy.’ David was typically frank about their achievement: ‘To say we climbed it was a plain untruth.’

When he returned, he began to feel unwell. His breathing became increasingly difficult. It was in fact the onset of poliomyelitis but he thought he had influenza. He decided to shake it off by cutting the lawn, the worst thing he could have done. While pushing the mower, suddenly he stiffened.. He was rushed to the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford, where he spent nearly a year in an iron lung. He was never to regain full use of the chest muscles and the controlling nervous system. But he remained as serene as ever, continuing to teach and research at Oxford and to play an active part in mountaineering circles. He accepted the Editor of the Alpine Club Journal in 1962 and was President of the Alpine Club from 1971 – 1973. Although conservative by instinct, he accepted the changes of the time, and during his presidency he prepared the ground (in the face of many die-hards) for the club’s amalgamation with the Ladies Alpine Club. He retired in 1984 as Vice-Master of University College.

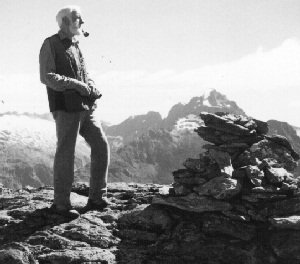

David’s connection with the YRC took root when he was the Principal Guest in 1974. Thereafter, Cliff Downham regularly asked him to the dinner, and a real friendship grew between many members of the YRC and this quiet unassuming don. In 1981 he was the Principal Guest a second time, when due to backword, he stood in at the last moment. I remember him saying before the 1981 dinner, when he saw Douglas Milner’s name among the guests, that Milner would have done it much better. And he was probably right, for in truth, David was too modest a man to be assertive as an after dinner speaker. The YRC was the sort of club he enjoyed. It had standards. Knowing how much David valued this contact with the club, in 1985 I had the pleasure of proposing his name as an Honorary Member. He regarded it a great honour to be included officially in our proceedings, particularly as he could now tell Cliff that he could pay for his own dinner in the future. He came out on the After Dinner Walks, using his sticks, enjoying the conversation, happy to be there, among the hills, the company and the friendship of the YRC.

Anyone meeting David during the late 1980’s would be excused if they found it difficult to imagine him in his youth, in North Wales, or the Alps, at the forefront of pre-war climbing. He had a good brain, (he had gained first class honours and was elected a Fellow of All Soul’s College in 1937), he was strong, and he had the build and balance of a gymnast. He was also meticulous and determined. When these qualities were understood, it was not difficult to imagine him on a rock face, in nailed boots or plimsolls, out on a long lead, when protection was in its infancy, assessing the possibilities, and when ready, making the move without haste. If others were better known, then that did not matter. He had had his sport. He had achieved what he set out to do and unlike others, he had survived. Despite his disability and the tragic death of one of his daughters, he moved through life without any rancour or malice. It was as though the mountains had given him an inner strength. This contentedness communicated itself to those who knew him and we would come away feeling the better. David Cox was an outstanding climber, but more important he was gentleman, whom to know was a privilege.

Dennis Armstrong

6 December 1994