The Watkins Mountains Expedition, 1969

by G. B. Spenceley

EAST GREENLAND: if you except the Antarctic, it is the longest and loneliest coastline in the world, and the most mountainous. Measure it out across the page of an atlas and it will stretch from London to the middle of the Sahara Desert. On its entire length live only 3,000 people, Eskimos, or Greenlanders as they prefer to be called, and a handful of Danish administrators and technicians. Little more is exposed than the coast-line for, beyond the narrow strip of fjords and mountains defended by an endless procession of icebergs and pack ice, the land continues under an ever thickening ice cap, 10,000 feet deep in places. A century and a half after the Danes had administered West Greenland, the East Coast still remained an unknown, unexplored waste, its stern shores seen only on rare occasions by adventurous arctic whalers.

One of the first of these was William Scoresby, junior, who in 1822 discovered the most extensive fjord system in the world, which now bears his name. Later in the century a handful of Danes rounded Cape Farewell in ‘Umiaks’ and pushed north. One of these, Gustav Holm, reached Angmagssalik in 1884 to find 416 Eskimos still living a Stone Age existence. Utterly separated from their kinsmen, they were the pitiful remainder of a once populated coast, whose further decline was saved only by the establishment, some ten years later, of Denmark’s first East Coast settlement.

It was to this section of the coast that the young and remarkable ‘Gino’ Watkins came on the first British Arctic Air Route Expedition of 1930-31. He set up his base a little to the west of Angmagssalik. Watkins is relevant in our story, not for his boat and sledge journeys, but for one significant flight. Flying from Kangerdlugsuak Fjord some 260 miles up the coast from their base, Watkins and D’aeth saw, far to the north, a new range of mountains towering above all their neighbours. So completely did they dominate the horizon that even from that distance the height and importance were immediately obvious. Thus were discovered not only the highest mountains in Greenland but in the whole of the Arctic. They were to be later named the Watkins Mountains.

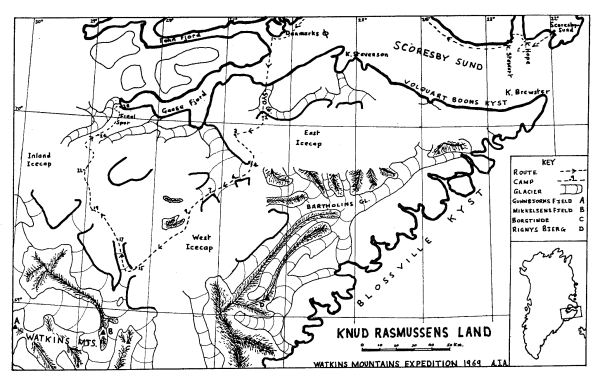

A further British Arctic Air Route Expedition in 1932 surveyed more of the coast, but still the outstanding problem of East Greenland was the 350 mile hinterland between Scoresby Sund and Mount Forel. The problem was one of access, for here, where the Arctic Current funnels the pack ice into the narrows of the Denmark Strait, the coast is only unreliably and briefly navigable. Even if a landing could be made there were steep and heavily crevassed glaciers to negotiate in the few weeks before the threat of closing ice would make return essential. It was these difficulties which caused Martin Lindsay —one of Watkins’ old team—to consider an approach from the west even though this would involve a 500 mile crossing of the Inland Ice with as great a distance again to cover before reaching the safety of Angmagssalik. It would be the greatest sledge journey, unsupported by depots or hunting, ever made. Only Amundsen’s South Pole dash of 1,390 miles was a greater dog-sledging distance.

Lindsay’s British Trans-Greenland Expedition, inspired by vast new mountain ranges, set out from Jakobshaven in May 1934. After a 500 mile, five-week crossing of the Ice Cap they saw their landfall of mountain tops to the east. Nearest to them were the Gronau Mountains, first discovered from the air and not again to be seen, except from the air, until our expedition was approaching the head of Gaasefjord thirty-five years later. Far to the south were the greater peaks of the Watkins Mountains. In the weeks that followed as they sledged south, inland of the coastal fringe, they succeeded in levelling their theodolite at the most mighty of these, a peak which is today named Gunnbjorns Fjeld, 12,200 feet high, thus lifting from the unknown and placing for ever upon the map, the Arctic’s highest mountain.

The challenge of this peak soon lured the French and the Italians, but both failed to make a landing in these nefarious narrows. Nowhere on the whole Greenland coast does the sea ice more strenuously defend the secrets of the land. It is called the Blosseville Coast after Jules de Blosseville who, in 1833, was the first to penetrate the Strait and the first also to pay the price. He, and all his crew, were lost. It remained unknown until the beginning of the new century when Amdrup, exploiting the narrow channel of open water, that in a good year may extend off shore, traversed the whole coast in an open boat. Amdrup’s companion on that journey was Ejnar Mikkelsen, gaining his first experience of polar travel and discovering what was to be lifelong love of Greenland. Not the highest, but the most magnificent of the Watkins Mountains now bears his name, and it was Ejnar Mikkelsen who was our honoured Danish patron.

Where the French and the Italians were defeated the British were more favoured. Wager and Courtauld, appropriately also from the old 1930-31 team, organised an expedition with the Watkins Mountains as their objective. For the summer of 1937 they chartered the “Quest” and sailed north from Angmagssalik. Their aim was to make a landing at Wiedemann’s Fjord which would give them the shortest and most direct approach to the northern end of the range. But far short of this point the almost inevitable barrier of ice halted their further progress. One cannot linger long in the few weeks of the short Arctic summer and they had to be satisfied with a landing close to Cape Iminger. They were still far south of their chosen objective but not all was lost. Unusually assisted by good fortune and fair weather, a small man-hauling party sledged a remarkably rapid route up the Sorgenfie and Christian IV Glaciers to the southern section of the range, from which they succeeded in climbing the great snow peak of Gunnbjorns Fjeld. There was time for little else.

The Arctic’s highest peak had been won but the enormous extent of basalt mountains to the north, less a little in height, but greater by far in magnificence, still remained unexplored and unclimbed. In the years that followed others sought to gain this mountain goal but were held back always by ice or bad weather. Today, thirty-three years after the one successful dash to Gunnsbjorns Fjeld these mountains and glaciers are still untrodden and may with truth be described as Greenland’s last great problem. Indeed if access is the criterion, rather than ascent, the Watkins Mountains remain the outstanding mountain problem of the Northern Hemisphere.

In 1968, Alastair Allan, a young and dedicated explorer, already with much expedition experience, turned his attention north to Greenland. A study of the field soon presented to him the problem of the Watkins Mountains and his imagination was fired by their challenge. Inspired by Amdrup, one solution was considered: to take an open boat either south from Scoresby Sund or north from Aputek—a Danish wireless station north of Angmagssalik. With the luck of open water such a scheme could bring the explorer within the shortest sledging journey of the mountains. But open water will always be problematical, and, in a bad season, with east winds pressing the pack against the shore, instant defeat would be a certainty. To stake all one’s chances on the fortune of the wind seemed ill considered and furthermore transport would have to rely upon the restricted sailings of the Danish Government vessels which serve the coast, thus imposing the limitations of a short season.

But a chance scrap of information brought another solution, which would not only lengthen the season and provide a new and intriguing route, but would involve the crossing of unexplored land right from the start, itself a worth-while objective.

At Reykjavik, Iceland lives Bjorn Polsen, a bold and enterprising pilot. It was learned that for years, with light aircraft, he had been operating an occasional ambulance flight to Scoresby Sund, landing on a few yards of dried out river bed. If he could be persuaded to fly out the expedition and stores, just as soon as the spring thaw permitted, we could be in the field three weeks before the first icebreaker could force her way through. From Scoresby Sund a crossing of the fjord ice and a back pack to the plateau would land us on the edge of the Inland Ice with only 120 miles to sledge to the mountains—all the way through unknown land.

But of course there were problems and uncertainties, the most vital of which would be the state of the fjord ice, which already in June would be in rapid thaw. And then too, there were the difficulties of the ascent to the plateau up one of the highest and most unrelenting cliffs in the world, a fault line 150 miles in length, mounting in basalt buttresses almost vertical in angle to a height of 6,000 feet. Such glaciers as do break the line and force their way down to the sea, do so only in contorted icefalls of fearful steepness that would brook no attack. Aerial photographs were studied in detail which suggested that at only two places in this, the south wall of the world’s longest fjord, did a route seem possible, at Kap Stevenson half way along its length and at Gaasefjord at its head.

The problems and uncertainties were to remain, but with all considered, an overland approach from Scoresby Sund, which at least had the novelty and virtue of being hitherto untried, seemed to offer the best chance of success and the plan was put into operation.

The decision was made to make it an Angh>Danish Expedition; the Danish Alpine Club was invited to contribute two members and soon a team was gathered with Alastair Allan as the leader. There was Jack Carswell, the oldest of the party but the most skilled and experienced mountaineer; Dr. Michel Barrault, a lecturer in electronics who was to be in charge of the wireless; the two redoubtable Danes, Vagn Christensen and Harry Vedoe, both with much Greenland experience, and myself as deputy leader. Polsen agreed to fly us out and, with more optimism than now seemed justified we set ourselves the task of raising funds. The Royal Geographical Society gave their support, the Mount Everest Foundation their money; donations were received from sources private and public, both here and in Denmark. We were grateful for the patronage of Lord Hunt and Ejnar Mikkelsen and deeply honoured by the financial assistance of H.R.H. Prince Philip and Prince Henrick and Princess Margrethe of Denmark. Finally, to ease our logistics, the Royal Danish Air Force agreed to give us an air drop. Interest in the expedition, far beyond our expectation, had been aroused and we suddenly felt slightly important people burdened with a frightening load of responsibility.

Alastair Allan left by sea for Reykjavik on the 13th June, soon to be joined by Jack Carswell and myself. We were seen off from Glasgow Airport by the Scottish representative of a whisky firm, and were photographed appropriately clutching between us a case of their product. Michel Barrault and the Danes arrived some days later.

It was intended to fly almost immediately to Greenland, but already our carefully thought-out plans were jeopardised by the adverse weather, with which throughout the summer we were to be cursed. For some days snow still covered the landing ground and when this had cleared we were held up by a procession of storms which swept up the Denmark Strait. Without navigational aids near perfect weather was essential for the flight, and for a week we suffered frustrating delay, conscious that each day was making our vital fjord ice crossing more perilous. Not until the 3rd July was there sufficient gap between the endless depressions and on that afternoon Vagn and I, with Peter Chambers, the Daily Express feature writer, made the first flight. In the light twin-engined Beechcroft Bonanza we flew out in improving weather, heading north-west over the pack ice. Meanwhile the remainder of the party and our stores were being ferried in a Cessna to Isafjardjup on the north coast of Iceland, there to await the further flights.

We banked low over the small cluster of buildings at Scoresby Sund and came in to a bumpy landing on the stony ground across the bay. Two Greenlanders with their dog teams and a handful of Danes were waiting to welcome the first summer arrivals. A bay which seemed more water than ice separated us from the settlement and expertly the Greenlanders leaped across the leads and drove their teams on broken and sometimes sinking floes. We innocents inexpertly followed and, within a few yards of the shore, Peter Chambers was up to his neck in icy waters; this was the fate that was to befall most of us that night. Ten hours and two flights later the whole party was assembled at Scoresby Sund. We were eight days behind schedule.

Scoresby Sund is the most northerly Eskimo settlement on the East Coast. Scoresby, and others who followed him, found evidence enough of former occupation, but it was not until 1924 that the present settlement was founded. This was the first effort at decentralisation made necessary by the combination of an increasing population at Angmagssalik and a steadily decreasing seal stock. It now has a population exceeding 200 — and 800 dogs — and it is still dependent upon a hunting economy.

It was some of the hunters of the settlement whose advice and assistance we now sought concerning the problematical 75 mile crossing of the fjord ice to Kap Stevenson. Most of those consulted simply smiled and shook their heads; but others, less pessimistic, said “imarer”. In a land where every journey is subject to the foibles of ice or water, wind and storm, the outcome is always uncertain, and “imarer”, meaning “perhaps” or “maybe”, is the first Eskimo word one learns.

Of those who admitted that perhaps after all it just might be possible were Boas, Jacob and Madigalak, three of the best hunters on the coast, and they agreed to attempt a dog sledge crossing to Kap Stevenson. On the 5th July we set out, seen off by half the population almost all of whom were convinced we would soon be back; or. if not quite so lucky, end up sitting on a floe drifting out into the Arctic Ocean. We remembered the words of the Danish doctor: “In three years”, he said, “I’ve only had one natural death”.

In fan formation, 10 dogs to a team, pulling heavy Greenland sledges, and towing our own light Nansen sledges, we sped at the speed of a slowly running man, across the ice, now patterned with a thousand pools.

The sun shone brilliantly down, the line of distant mountains on the far shores of Scoresby Sund was still as far away as is France across the English Channel, but in this crystal clear air even Kap Stevenson no longer seemed remote and our spirits, dulled by days of inactivity, were now high and our mood was optimistic. But alas the Greenlanders did not share our feelings. Only a few hours out and an open lead split the ice for a mile or more; it was an ominous herald and there we halted with much solemn shaking of heads. Perhaps even more ominously we could now see open water, but if this reduced our spirits further, to the Greenlanders it was like a magnet. They crossed the lead and hurried forward, no longer with any mind for the fjord crossing, possibly with no hope for one, but only now with the thought of hunting. Open water meant seals and the Greenlanders’ deepest instinct and greatest delight is to hunt. Soon they were on their stomachs, their rifles steadied on a rough wooden stand, eagerly awaiting the seals’ surfacing. Sadly, a dozen were killed before one floated, and bullets whined past us as the hunters fired with little regard for any human in the line of sight. We understood even better the dearth of natural deaths.

Our camp that night out on the ice was one to be remembered. The far mountains, lit in pastel shades by the subtle light of a sun that dipped but never sank, had an unreal beauty.The Eskimos, ever alert behind their rifles, and the lines of tethered dogs, gave the scene a Greenland atmosphere that we would never again so fully capture. The Greenlanders, emphatic that the break up had already started, suggested they return for an open boat while we man-hauled to Kap Stewart, the nearest point of land on the northern shores, to await their arrival. This last we attempted to do, but soon we found ourselves on fast flowing ice floes noisily grinding together in rapid and alarming movement. Concerned at the hazards of this unfamiliar element we promptly turned around making instead for the isolated Eskimo settlement of Kap Hope. Even this we could not have reached but for the assistance of the friendly people of this place who came pole vaulting over the floes to our rescue. The crossing of the fjord ice, the success of which was so vital to our plan, had failed.

At Kap Hope we waited for two days enjoying the hospitality of these endearing people whose warmth of character is a direct contradiction to the bleak severity of their background. Civilisation may have touched their life with its radios and rifles, its sewing machines and outboard motors, but here, where the Eskimo can still retain the ways of the hunt, travel with his dog team and paddle his kayak, the traditional qualities of humour, honesty and hospitality have not been lost. We felt very privileged to be their guests.

Our Greenlanders returned and on 8th July we set out in an open 15-foot boat powered by two outboard motors. Our own inflatable boat, loaded with stores and the two sledges, we towed behind us. Almost immediately we suffered a day of high wind, but if this delayed us it did hasten the break up of the ice. We crossed Hurry Inlet in much open water, but with so little freeboard that we feared for our safety. We rounded Kap Stewart, where musk ox grazed, and for two days followed the coast of Jameson’s Land, sailing a zig-zag pattern through the leads. Never before had a boat forced her way so far, so early in the season.

The next day and night was to be the climax of the voyage, with the outcome uncertain until the very end. Kap Stevenson was now about 30 miles away across the fjord, but where a sudden wind would spell disaster the Greenlanders were most reluctant to risk their craft so far from shore. At last we persuaded them to try and hopefully headed out into open water, only an hour or so later to be halted by unbroken and unyielding ice. Back we came disappointed and despondent but not yet defeated.

Another thought had occurred. If we could not reach the south shore of the fjord perhaps we could cross the wide mouth of the northern arm of Scoresby Sund to Milne Land. Again we headed hopefully out, again ice barred our way and again the Greenlanders urged our return. But Vagn’s gentle persuasion won the day, and exploiting what few open channels there were, we threaded a tortuous course between the floes. Twice we halted to mount icebergs to scan the way; it seemed advance was impossible and even return unlikely, so hemmed in were we by ice with hardly a glint of water. It was bitterly cold, the sea was freezing and we shivered as we sat uncomfortably cramped in the boat. The sun had now reached the limit of its northern dip, casting a soft light on the mottled surface, so beautiful that even in discomfort and uncertainty it was impossible not to feel uplifted by the magical quality of the night. Both shores were now equally distant, both seemed equally unattainable, but slowly we persevered through ice so rotten that we could split it with poles or axes and force the floes apart. Slowly the mountains of Milne Land came closer, Suddenly, unexpectedly there was open water patterned only by the reflection of a hundred icebergs. For 20 hours we had been afloat and now, with the issue less in doubt, we pulled up on to a floe to cook a meal. The sun was high in the south when we waded ashore just off Kap Leslie. Kap Stevenson was as remote as ever but the crossing to Milne Land had made possible an alternative plan. A day’s sailing round the coast from Kap Leslie was Denmark’s Island where a Danish geological expedition had a forward base for their helicopter. At £100 an hour its charter would be vastly expensive, but a prompt air lift to the plateau could put us back on schedule. Alas this was not to be. Permission to charter was received by radio from Copenhagen, but the helicopter was operating elsewhere and we were to suffer the frustration of a ten-day delay.

The dreary wait ended on the 22nd July. The helicopter came in from Mesters Vig and in worsening weather took off again on the first lift with Alastair and me on board. In a few minutes we had done what would have been a long day’s sailing over the fjord and were mounting the heavily crevassed Syd Glacier, the ascent of which on foot would have taken a week, if it had been possible at all. We emerged at its head on to the plateau where the horizon was lost against the cloud and the anxious pilot nearly turned round again. I was urged to throw out markers; down went an orange bag which was almost immediately lost, but another marker we did retain in sight and we were soon safely down beside it in a wild flurry of snow. Ducking below the rotors we hauled out the gear and we were left alone on the Inland Ice. We set out to recover the orange bag; it contained all the expedition’s tobacco.

The pilot was shaken and attempted no further flight after his return that night. He did not in fact come back until the following evening, when in two more lifts he brought in the rest of the party and stores. At last, a month after our arrival in Iceland, we stood beside our sledges on the edge of the unknown. There was something rather final about the helicopter’s departure.

For the sake of better sledging surfaces we were to travel at night and, with the snow already hardening, we were anxious to be off. Sledges were loaded, skis put on, harnesses donned and we were on our way. It was thirteen years since I had last pulled a sledge and within as many yards the awful truth returned; of all methods of travel, man-hauling is the most ponderously slow and relentlessly gruelling. We pulled for only four hours that night and covered as many miles, then we made camp. To muscles softened by inactivity it seemed far enough. It was —20 °C, with enough wind to make it seem bitterly cold.

The next night we were gently mounting over the East Ice Cap. The landmarks at our backs dropped below the horizon, no new ones appeared in front; it became a plateau of ice with nothing but our tracks behind to catch the sweep of the eye nothing ahead to give direction. It was difficult to steer a straight course even with constant compass corrections. A glance back showed a wandering wavy course that was wasteful of both effort and time. We were pulling a total of 1,200 lbs. and if we covered a mile an hour it was fair going; often it was half that speed. A short break after every hour’s hauling gave muscles and back welcome relief, but it was too cold to linger long.

At midnight with the sun like an orange flare burning just below the horizon, we erected a tent into which we all crowded for soup and a brew. Such halts became the routine of every night of travel. An hour later the sun had returned, projecting long pencil-like shadows far across the snow and then ahead the tip of a far away mountain slowly climbed above the sky line, another appeared, and then another, until the whole of the forward horizon was broken by lines of nunataks, all bright red in the morning light. When we made camp we were looking down on to a vast system of un-named glaciers. We knew that we should have to descend some 2,000 feet or more into this glacier basin before we could begin the long haul to the West Ice Cap. A careful study of the aerial photographs suggested that at only one place was a sledging route possible and it was for this break that we now searched. All we found were steep icef alls and steeper buttresses. By some miscalculation, or magnetic anomaly of the underlying rock, we were 60° off course and it took us half a night’s travelling to correct the error. The new day was well on its way before we were on the proper line of descent and the sledges ran free as we-gathered speed towards the broad break for which we were aiming. Only the Danes had the skill to control a fast moving sledge on skis; there were many tumbles before it became too steep and we completed the descent on foot. It was our longest night and day of travel, but hunger and fatigue were forgotten in the stimulation of faster progress and new and exciting horizons.

It had been excellent weather, cold indeed, but with unclouded skies and constant sun. These were the anticyclonic conditions that we fondly believed were characteristic features of an East Coast summer. After a bad start the weather had at last reverted to its normal brilliance and with gathering fitness we would make an ever increasing speed to our mountains. Such were our optimistic thoughts as we settled down to sleep on the morning of the 26th July; nothing could stop us now.

But more than optimism was required to counter the inclemency of this most perverse of summers. Our sleep was disturbed by rising wind and in the evening when we made breakfast it was blowing a blizzard; it was still blowing when we made a meal in the morning. It continued to blow for a further 48 hours and what had seemed at first to be a minor lapse in the weather, giving welcome excuse to refresh tired muscles, was becoming a serious threat to progress. The dismal pattern of snow and storm, with which we were to be almost continuously cursed for the next four weeks, had now set in.

It was obvious that we must travel regardless and, when enough visibility returned to see the base of the nunataks six miles or so across the basin, we loaded our sledges. For four nights we travelled beside a line of alternating icefalls and basalt buttresses following the course of some vast nameless glacier whose bounding walls we only vaguely and intermittently saw. For much of the time we could see only the tips of our skis or the man in front, or now and again the dark depths of a crevasse. It continued to snow and the sledges ploughed deep, limiting the effort of an hour’s labour to half a mile. Camp VIII was made after hauling all night in a blizzard which had reduced our pace to a crawl. Spurred by the urgent need for progress we had struggled on, until exhausted by an effort out of all proportion to the result, we had made camp, exchanging weariness for the discomfort of wet sleeping bags.

A matter of growing concern, adding a further spur to make an all-out effort to cover distance, was our increasing need for an air drop. We had originally planned to receive this at the highest part of the West Ice Cap, where we could leave a depot before descending to the Watkins Mountains. It was now evident that far short of this point our dwindling food stocks would make an air drop essential and accordingly we now radioed Mesters Vig, where the Catalina of the Royal Danish Coastal Command was based, requesting a drop on the first fine day. If the bad weather continued the situation could become critical.

But a brief respite from the depressing pattern of blizzard and snow was on its way. On the evening of the 1st of August the clouds suddenly rolled away revealing splendid vistas of vast rock buttresses that, unseen and unsuspected, had been towering above our camp all the time. With the clearing skies came a drop in temperature that gave us a consolidated surface and our best night of travelling. For once man-hauling was almost enjoyable. Encouraged by fast and easy progress we should have continued through the day as well, but by the time we had made the morning radio schedule, the snow softened and once more we ground to a halt.

The sun shining from the cloudless sky was so warm that we could take our ease comfortably in the open while we dried out our sleeping bags, soaked from a week of wet camps. In the afternoon we heard the unfamiliar note of aircraft engines and we switched on the radio homing beacon. We lit a smoke flare to give wind direction and the old wartime Catalina flying boat slowly circled our camp, losing height before making the first run in. Down came a case of whisky on a yellow marker parachute, followed by boxes of food and the mountaineering equipment. Dipping its wings in a last low flight, the Catalina departed.

There was food galore and delicious luxuries like peaches and cream and cans of refreshing orange juice. We sat on the sledges scoffing these welcome delicacies, like children at a party. What was less welcome was the enormous addition to our load, days before we could leave the depot. Just how much slower we should now be we discovered that night, although weight alone was not responsible. It was our second night of hauling with no interval of sleep between and our strength was sapped, not only by this additional burden to our toil, but a little by fatigue and even more by an all enveloping cold, more intense than anything we had known before. It was — 25 °C, which alone is not too bad, but there swept off the plateau a harsh wind which dulled our minds, weakened our resolve and seemed to penetrate to our very bones.

The sun made its brief dip below the mountains and a greyness gathered across the surface. But what the snow lost in colour the sky gained, and we six stooped figures wearily shuffled our skis against a vivid orange light, like the back-cloth of some stage extravaganza. It was breath-takingly beautiful, but gloves could not be removed and no photograph records its splendour. When we made camp, Vagn and I had frostbitten toes and fingers.

We were to have a further day and night of cold brilliance, otherwise the next two weeks were a nightmare of almost continuous white-out, soft surfaces and impossible navigation. For ten days it snowed and on only four days did we briefly have visibility. The depth of soft powdered snow increased daily. Off skis we would plunge to our thighs and the sledges ploughed ever deeper. Relaying sledges became the necessary but tedious and time-consuming routine. The output of a night’s toil could be as little as three miles. So far did we fall behind a schedule already much damaged, that the prospect of ever reaching the Watkins Mountains, never mind climbing any of them, became increasingly remote. We were to be picked up at Gaasefjord on the 24th August and, with the Sound soon to freeze and the departure of the last ship at the end of the month, there could be no latitude, even if our rations were to be stretched.

With visibility reduced to occasional brief and restricted glimpses it was difficult to assess our position, but what little we did see included a snow dome recognisable on our aerial photographs. We were well on to the West Ice Cap and on the 12th August, when the ground fell away gently before us, we knew we must have reached its crest. Our height was 8,600 feet. If only the clouds would roll away we should be looking at one of the finest mountain scenes of the Arctic; as it was we could hardly see the tent next to us. Only twenty miles down an unseen glacier before us, a night’s travelling with a lightly loaded sledge, and downhill all the way, was Ejnar Mikkelsen’s Fjeld and all the other fine mountains which for so long had been the centre of our thoughts. We were nearer to them than anyone had been before, but blizzard and soft snow had done their work, and time had run out. We must turn our backs with the Watkins Mountains still unseen.

The decision to return was too clear cut for there to be any dispute. It had taken us 21 days to reach this point; we had eight days less in which to make the equally lengthy return to Gaasefjord. We could hardly extend our rations further, and we had such imponderables as a difficult spur to negotiate and the uncertain descent to the sea. The wisdom of our decision was shortly to be confirmed when a radio message was relayed to us stating that Gaasefjord was reported blocked by ice. This was a blow indeed; the only alternative pick up point was Fohnfjord, a thirty mile backpath to the north. We had no choice but to radio a request for the vessel to pick us up there on the 26th August. Any prolonged onslaught of bad weather, or an error in navigation, would create a critical situation. Speed was now essential to our safety. One sledge was abandoned and all equipment except what was deemed necessary for survival.

We were fit and determined men urged by the spur of necessity; but despite all efforts the next night’s hauling produced only a paltry three miles before once more we were bogged down in blizzard and soft snow. But the high wind was to produce some comfort; it gave a consolidated surface. The following night we made excellent progress in conditions that were otherwise far from good; it was still snowing and blowing and our faces became unrecognisable behind masks of ice, but we covered 12 miles or so.

Navigation was the problem. For the next seven nights we were to travel in a permanent white-out, setting our course by dead reckoning with no sledge wheel to assess distance; this had earlier been damaged and discarded. Nights became darker and our spirits ebbed with the light. We pulled in silence— except for the call of compass direction—each enveloped in his private misery. At the best of times man-hauling is monotonous drudgery; in these everlastingly frightful conditions, when we saw nothing for days but the tips of our skis, it became utterly loathsome. Always before we were stimulated by the prospects ahead; now we were defeated and anxiety replaced ambition.

We had some reason for anxiety. We knew that the exit from the plateau could be a difficult and time-consuming operation. The key to the problem was a long spur of undulating ice cap that thrust itself between two nameless glaciers running down to Gaasefjord. The glaciers themselves we had dismissed as impassable. At the end of the spur the photographs suggested that a glacier led gently down almost to the moraine. But we had already learned that aerial photographs can be deceptive. Seen from a great height angles are lessened, difficulties concealed, and there was no certainty that either the spur or the descent from it would be easy, or even possible. With each night of travel like the last, groping our way through a white-out, anxiety increased, for without visibility we could never find the spur and, even if we did, could travel along it only with the utmost difficulty. The uncertain accuracy of our navigation was another cause of concern. We had food left for only eight days.

The very uncertainty of the situation, however, created some-thing of a challenge and, even with prospects seemingly so cheerless, our spirits were not low—except of course for those gloomy hours through the middle of the night when every foreboding thought was magnified by cold, fatigue and boredom. It was partly to spare us this, and partly the better to exploit any return of visibility, that on the 19th August we changed to day travelling. With this change came the miracle. In the evening the wind veered to the north-west, the temperature dropped to — 30°C and the clouds dispersed. Still far ahead, but exactly in the line of travel, we could see the dark waters of Gaasefjord. For two weeks we had travelled without visibility and we emerged from the murk exactly where we wanted to be. None of us will really know if it was the result of brilliant navigation or incredible good luck.

We camped that night where we could see the long spur we had to follow, trying to assess the angle and depth of its depressions. Given good conditions it would take at least three days to reach the end and we wondered if the weather would hold so long. Without visibility, navigation along its crest would be extremely difficult. There were a dozen subsidiary ridges, any one of which could be followed in error, all of which would lure us into an impossible situation. The spur was defended by miles of vertical basalt, alternating with icefalls of frightful steepness. To follow a false course would mean either precious days wasted in reconnaissance or abandoning the sledge and involving ourselves in a massive problem of major mountaineering.

But good fortune sometimes favours the incautious. Just at the time when it was most essential to our safety and progress, we were to have visibility. For three days, and the whole length of the spur, we enjoyed brilliant weather. The next day we contoured the head of a glacier to the foot of the first depression and in a slow but steady rhythm hauled the sledge 1,000 feet up to the first summit of the spur. It was desperately hard work but even the mid-day sun did not soften the snow, and we pulled for once on a good surface. A shallower depression followed, then miles of level going before again the angle steepened to plunge, this time at least 2,000 feet down, to a narrow col. Reconnaissance was needed and we camped on a shoulder half way down the slope above buttresses that fell 6,000 feet down to the main glacier. This must be some of the finest basalt scenery in the world.

Brakes round the runners were necessary to control the sledge on the descent to the col and all the time we were looking at the frightfully steep slope opposite, wondering if we would have to haul half loads. Half loads or full, it was going to take hours of back breaking toil and we briefly considered the possibility of descending here to the main glacier. The icefall to the west of the col looked less intimidating than the others. But we could see only its upper half and we dare not commit ourselves without a reconnaissance which would take most of the day. Even if we could get down, there was still twelve miles of the main glacier which was so contorted and creased by pressure ridges and crevasses that we should be reduced to back-packing along the moraine. It was a poor alternative and with a will we put ourselves to the slope, worried lest any slackening of the tension should cause the sledge to take control and hurl us back to the col and over the icefall. We dared not pause for rest until the angle eased off. We made our next camp on the bottom of yet another depression with another steep rise ahead.

Wishfully discounting the difficulties, we thought of this as positively the last camp on the snow. Tomorrow, after the first hard pull, it would be down hill all the way to Gaasefjord, to a blissfully new world of colour and comparative warmth, to a friendly world where animals and birds lived and plants grew, to a lush greenness and softness that all of a sudden seemed infinitely desirable. Never mind that no vessel could get into Gaasefjord and there were still 30 miles of backpacking. The route to Fohnfjord was low, all the way over the tundra. Hard going though it might be, it would be beside running water and lakes and with all the splendid display of colour that closes an Arctic summer. Except that the nearest humans were 150 miles away, and there were icebergs in the fjord, it would be like Scotland in the autumn.

But it was not to be. We were soon going down hill but alas not yet to Gaasefjord; we were to be exhausted and hungry men before we reached those shores. Soon after mid-day we arrived at the crest of the glacier that, according to our photographs, offered, among a number of uncompromising routes, the only line of descent. Two reconnaissance parties circled its head. Both parties returned disconsolate. Not only was the lip defended by a series of vertical ice steps but the glacier descended at a frightfully steep angle to an icefall of chaotic seracs, there to plunge into depths unseen. This, the glacier of our choice, proved, of all those seen, to be the least possible. Happily, on our reconnaissance Jack had spotted a less alarming alternative. The eastern arm of the glacier basin, and the true terminal of our spur, passed over a series of snow domes linked by narrow ridges. From the last of these summits it then seemed to fall at an angle, neither broken nor too steep, far down towards the main glacier. We had no certainty that it could be descended, but there was positively no alternative. It would be back-packing all the way.

We contoured the head of the glacier nursing our sledge at an angle where only two could be spared for hauling, the rest of us exerting all our strength to prevent it rolling over the ice cliffs and taking us all with it. It was alarming and possibly very dangerous. The snow domes and the ridge which we now followed in the soft evening light of that long day gave us the finest views of the whole expedition. At one side the ridge fell steeply on to the chaotic icefall, on the other it plunged down 6,000 foot cliffs to the green ice-mottled waters of one of the world’s wildest and most remote fjords. Our camp that night, where the ridge so narrowed that further sledging was impossible, was the most magnificent we were ever to occupy. It was also our last comfortable night.

The date was the 22nd August and we had food only for another three days—and that was on half rations. We thought with deep gratitude of the good weather with which we had been blessed and wondered where we should now be without it: probably still groping our way on the Inland Ice seaching for the spur. But our luck with weather had now run out. When we got up in the morning dark clouds were massing in the west and already the mountain tops opposite were disappearing in cloud. Michel erected the aerial and tapped out the daily report to Reykjavik, 500 miles away. A message from Scoresby Sund was relayed back to us; the vessel ‘Entalik’ was being despatched to Fohnfjord to pick us up there on the 26th August.

We packed our gear and found there was little we could abandon except the sledge and one tent. There were our magnifi-cent and expensive skis of course, but these each one of us cherished most dearly and we added them to our load. We estimated we were carrying over 80 lbs per man, and thus weighed down, we faced into the gathering blizzard to begin a nightmarish two-day descent. Jack Carswell, always more a mountaineer than a sledger, led the way, happy to be off his skis and clutching an axe. He cut steps round the base of one snow peak and to the summit of another. We staggered after him.

Staggered is the operative word and our legs, backs and shoulders ached after only a few yards; blinding snow blew savagely into our faces. It was all rather unpleasant but our greatest concern was route finding. We had to descend, virtually blind, 6,000 feet down a complex rock ridge or face—we could not yet be sure which—of a mountain that no one had ever seen. With such loads, and lack of food and time, we could hardly be involved in difficult or prolonged rock work. But, although the weather had turned sour on us, we still retained some luck. The ridge, for that is what it proved to be for half the way, went better than expected. Certainly we could see nothing and angles were impossible to assess so that we roped up, lest we floundered over some awful steepness, but we did make easy progress and steadily we lost height.

After several hours, rocks started to break the surface and, a little lower, we were reeling on awkward block scree where our unstable loads became almost unmanageable. When we fell, which was often, we had to be assisted to our feet. Now the snow was wet, adding an enormous moisture content to our loads, and we ourselves were thoroughly wet, so that in a state of considerable fatigue we abandoned our six pairs of beautiful Norwegian skis. It was just as well, for soon we were involved on steeper slopes with many rock escarpments which, if we could not turn, we had to climb or abseil. We were getting weaker and suddenly we realised we had not eaten for 12 hours, so we briefly halted to munch a dry meat bar. We were now nearing the cloud base and we caught glimpses of the massive glacier below. After a lengthy reconnais-sance we descended to it down the only weakness in a line, miles in length, of otherwise uncompromising crags. Soaked to the skin we made camp in a state close to exhaustion.

But it was a camp that held little comfort for the six weary occupants of a pair of leaking two-man tents. Between fitful sleep we pondered on the prospects ahead. Certainly it was a relief to be off the plateau and we were deeply grateful that we had stumbled, on what we later learnt, was the only feasible line off an otherwise formidable mountain; but our worst trial and perils could still lie ahead. We were below the main steepness, but, before we could even begin the crossing of the pass to Fohnfjord, there was a long day ahead of moraine and glacier which would tax us badly. The boat, safety and unimaginable comfort, might then be only another 30 miles, but who was to know what difficulties there might be on the way, the only guide to which were the same photographs that had flattened out the terminal glacier of the spur. As we shivered in our tents that night we began to consider the wisdom of committing ourselves in such a state of fatigue, on reduced rations, and in this appalling weather, to a route that could take many more days than three. Already there was a good coating of wet snow and our dream of pleasant streams and sunny green meadows had long since vanished.

In the morning there was a further foot of fresh snow and this was the final factor that caused us to abandon all thoughts of crossing the pass. Already debilitated by our earlier efforts and a growing need for more food, the combination of wet, cold, and deep snow could so delay us that we might well collapse with exhaustion and hunger. To struggle on regardless in such conditions would be folly. We would radio our decision and await results. We felt certain that once our situation was known, the ‘Entalik’ would make strenuous efforts to force her way through to Gaasefjord. Anyway the helicopter might still be at Denmark’s Island.

Things were not going to be quite so simple, however. Shut in below high mountain walls we failed to make radio contact and failed again at a second schedule later in the day. If this loss of our radio link was to continue we would have no choice but to go to Fohnfjord; either that or wait for days without food until some expensive and embarrassing rescue operation could be mounted. Anyway we still had to go down the glacier.

Actually the glacier itself proved far too crevassed, so we staggered and stumbled down the moraine at its side until our further progress was barred by a giant cliff, that as far as we could see extended across the whole width of the glacier. It was far too high to abseil. But now the bounding walls had lessened. There was a path to the east to which Alastair and I climbed. This was the solution to the problem; from its crest we could see an easy line of descent all the way to Gaasefjord.

We camped a few miles short of the fjord, well in the open, selecting our site to give radio signals the best chance. It had been a shorter day than the descent from the plateau, but almost as gruelling, and again we were in a state close to exhaustion. We ate our meagre meal, felt just as empty after it, and sought some warmth in saturated sleeping bags. For some of us there was no sleep at all that night, just hours of constant shivering.

From our tent the next morning we could hear the tapping of the morse key. This was a tense moment and there was enormous relief when Michel gave a smiling acknowledgement to our anxious enquiries. His signals were being received and he reported our position and situation. At mid-day a not entirely comforting reply was received. It read, “Entalik in Fohnfjord, radio contact lost, no helicopter available, greetings.” Briefly we reconsidered the walk over the pass, but our rations were now reduced to one-sixth of a meat bar per man per day—a mere 65 calories—and when we tested our strength a few yards from the tents the idea was quickly dismissed. Instead we moved camp to a position overlooking the fjord where we judged we could be easily seen.

There followed three days of hungry waiting. We were dis-comforted rather than concerned by the present lack of food; it was the uncertainty of future prospects that caused us most anxiety. If the radio link with ‘Entalik’ could not be resumed we might be here for another week, and there was the additional fear that, however strenuous the effort, the vessel would be repulsed by the excessive accumulation of ice in the bottleneck 20 miles down the fjord.

Of course we knew we should be picked up somehow, but it might take a long time, and our last wish was for an embarrassing American helicopter rescue from the West Coast. We flinched when we thought of the headlines. Meanwhile we would make the best of the situation and see what food we could find round about. There were some suspicious looking toadstools, and being assured that few specimens were poisonous, I tasted a small portion. I was questioned regularly on the state of my health, and when it seemed I was not going to die, we all rushed out to collect a panful. It was an evil smelling brew that we served out.

At last on the morning of the 29th August we heard gunshots from the fjord. Michel was on the radio at the time and he sent his closing message; they would listen for us no more. It was some time before we could see the red hull of the ‘Entalik’ looking so small and lost among the icebergs. We waved the orange sledge cover and I poured the remainder of our paraffin on to some vegetation we had dried out. Others took the tents down and packed loads. The boat swept the head of the inlet, but it was only now when we had something to give scale to the scene that we realised the massive architecture of the fjord. It was soon obvious that they had not seen us; our tents and banner would be lost in this vast landscape. We did all we could to attract attention, but slowly the ‘Entalik’ sailed away and disappeared, even out of the vision of our glasses.

We had radioed our exact position and it seemed astonishing that they had not searched for us more thoroughly. The hurried departure of the ‘Entalik’ could only mean that closing ice was threatening the exit to the fjord. Our brief joy at imminent rescue was suddenly replaced by a mood of profoundest gloom. We could make no further transmissions, we had neither food nor fuel, fog was creeping up the fjord, it was again snowing hard, the tents leaked, we were already wet.

For ten hours we pondered on the bleak prospects, resigned now to a long wait. But in the evening our gloom was suddenly lifted; unmistakably we could hear the throb of a diesel engine. The boat was returning and through the glasses we could see it searching the south shore of the fjord. And there it remained; obviously they were mistaken about our position. Nobly, Jack and Vagn set off to walk the five miles round the coast—a fine effort for anyone in our weakened state.

Some hours later we were in the warm cabin of the ‘Entalik’ with endless mugs of black coffee and food unlimited. For 40 hours we did little else but eat and sleep as we battered our way down the fjord in yet another storm. At Scoresby Sund the Danish administrator came down to welcome us. “You have done well”, he said, “the East Coast has had the worst summer within living memory.”