Turkey Again. 1967

by J. R. Middleton

After our return from Turkey in 1966 we at once decided to organise a further expedition, but this time with not quite such a large party. All went well until June 1967 when for various reasons our six-strong party was suddenly reduced to two, just Tony Dunford and myself. However, as most of the arrangements had already been made and as we knew that for at least half of our stay of three weeks we should be with Dr. Aygen, we decided to go it alone. Both of us were flying out so the amount of equipment we could take with us was seriously reduced, but as things turned out we did not need all that we did take.

We arrived only a few days before the Speleo Club de Paris were due to return to France. They had carried on with the exploration of Diidensuyu, the resurgence cave further up the Manavgat Gorge from Dümanli, about 1½ miles from the village of Ürünlü (Map 1) and briefly mentioned as having been found in the last two days of the 1966 expedition. Here they had discovered over a mile of very large passage with sporting climbs, deep lakes and many incrustations. During their last few days they had found a very deep pot, Diidenjik, and when we arrived they invited us to join them; it proved to be the deepest pot-hole yet discovered in Turkey.

Apart from Düdenjik we ourselves discovered and explored a total of 9,900 feet of passage, including one river cave of almost 6,000 feet which went completely through the mountain. That there were only two of us proved no great disadvantage except that we were not able to descend deep holes; an advantage was that we were obliged to live with and rely much upon the local village people, we thus got a valuable insight into their way of life.

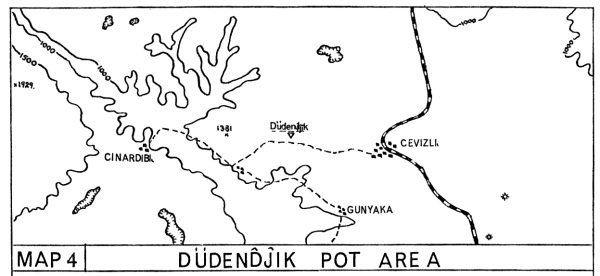

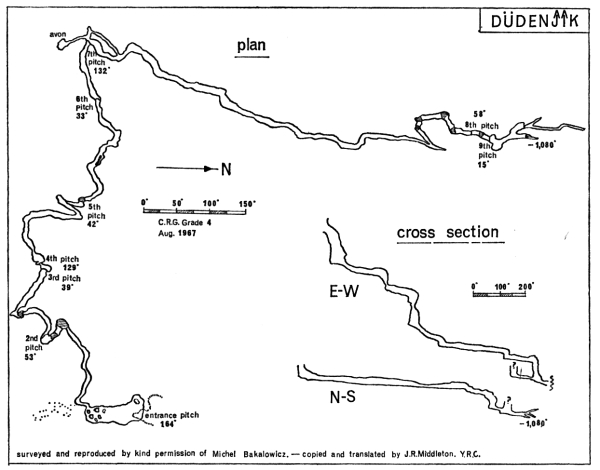

Düdenjik (Depth 1089 ft., Length 2475 ft. Map 4 and Survey)

No sooner had we touched down at Antalya airport than we were whisked away by Ali, Dr. Aygen’s chauffeur. Some four hours and many reminiscences later we passed through Akseki, the northern limit of our 1966 explorations, and continued on up the Beysehir road until after about 15 miles we reached the village of Cevizli. Here, before continuing our journey, we had time to renew our acquaintance with the heat, dust and smells so typical of this part of the world. Three more miles westward along the Cinardibi dirt road and we reached the French camp site in the midst of tall pine trees. Down one side of the camp ran a dry stream bed which went a further hundred yards into a small rock outcrop at the base of which was a 20 ft. diameter shaft.

Tony and I, with six French, started down early next morning after a large breakfast. The descent for the top 40 ft. of the shaft is at an angle of about 80° over a layer of calcite, the next 134 ft. is practically vertical and finishes in a very fine chamber. At the end opposite the ladder a steep boulder slope leads to a high passage finishing at the head of a 53 ft. pitch covered with flowstone. The gallery at the bottom is again large but soon comes to an abrupt stop six feet above a deep lake. Here the French used a dinghy but to get into it needed an unusually acrobatic movement—the descent of a deep shoot with no holds and a delicate drop of two feet into the boat. It was not uncommon to overshoot the dinghy and land in the water, this meant having to swim across the 20 ft. wide lake.

A gently meandering passage led to an easy 39 ft. drop on to a large ledge with a deep pool. Then came a pitch of 129 ft. which I consider to be the finest pitch that I have ever descended. It is perhaps 30 ft. across and the walls are of a light coloured limestone partly covered with calcite. About 60 ft. down one suddenly goes down under the bottom of a flowstone cascade and hangs free in a 40 ft. diameter shaft. As one continues to pendulum down, giant wall stalagmites reach up like grotesque fingers fifty or more feet high; to look back up as someone else is coming down is an unforgettable sight.

Between this fourth pitch and the next big one are two smaller pitches, the fifth of 42 ft. and the sixth of 33 ft. The seventh is 132 ft. and at the top of it the French had made a little camp with stocks of food and stoves; as might be expected we stopped for a quick snack. The shaft is again a fine one with a gully type ledge about 60 ft. down; from there to the bottom the ladder hangs just away from the wall. The only side passage now enters the system, dividing after a few feet, the left branch going to a large aven while the right hand one returns as an oxbow to the main passage. At this point also the first running water enters the pot, only a few drips but very conspicuous in that it leaves a black precipitate on the yellow flowstone. The next section, the longest between pitches, was the most sporting—jumps and traverses over pools, good climbs down short drops and a winding razor-edged passage leading to the eighth pitch of 58 ft.

This proved a rather awkward pitch as the ladder persisted in hanging at an angle different from that of the walls, in addition to which one had to get off on to a narrow ledge above a deep crystal pool. A short passage led to the final pitch of 15 ft. into a chamber with just one low crawl leading off. We followed this to another chamber but this time with no exit except a high level fissure; the French climbed up to this but it could only be followed for a few feet. A disappointing finish, but a tremendously sporting pot, much deeper than anyone ever expected.

The Uzunsu River Caves

The village of Camlik (pronounced Chamlik), near to the caves, is perhaps one of the most beautifully situated of all the villages that we visited on our expedition. On three sides it was surrounded by the bright yellow stubble of freshly cut wheat and in the two nearest fields the wheat itself was being threshed by the women in their brightly coloured baggy trousers. Behind the fields and on the fourth side of the village are mountains, the startling barrenness of the limestone contrasting magnificently with the isolated patches of dark green scrub. Immediately upon our arrival the very friendly villagers insisted that we use their school as our base—the children have the four hottest months as a holiday—so beneath the many watchful eyes of Ataturk we accepted their hospitality. They were very interested to learn of our proposed visit to the caves, no exploration by them had ever been undertaken, though the entrance was used as a shelter for their goats.

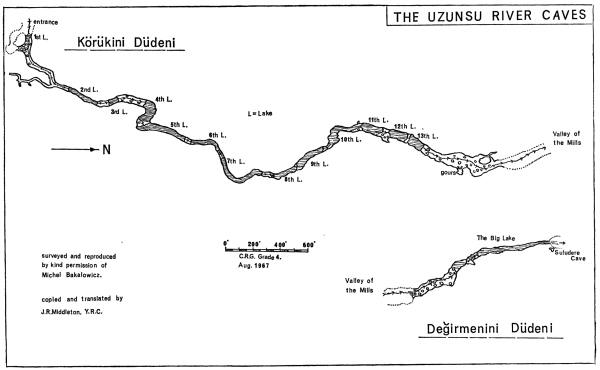

Körükini Düdeni. (Map 3b, Survey, Length 5,850 ft.)

On the south side of Camlik a track follows the edge of the mountains for almost a mile into a small gorge carrying the Uzunsu River. This twists and turns its way past two small and unexplored caves until it reaches the entrance of the first river cave. The size of the actual opening completely took us by surprise; a conservative estimate would put it at 80 ft. high and nearly 40 ft. wide. That this place had never been explored before seemed almost incomprehensible to us. Immediately inside the entrance is a deep pool the width of the passage; to avoid this our village guides pointed to a smaller opening up to the right. This led us down on to a big boulder slope at the other side of the pool. The cave inside is just as big as the entrance and we felt at once that there was a very good chance that it was negotiable right through the mountain, as shown on our survey.

Our party consisted of Dr. Aygen, a meteorologist friend of his, a very fit Turk from the village, Tony and myself. Exploration began at once; we moved down the giant boulder strewn passage only to find that our English carbide lamps were about as much good as a number 12 hook is to a shark fisher. Within 100 yards we were up to our knees in water and at an abrupt left hand turn we were out of our depth. At this point an inlet comes in from the right, we did not explore it but Michel and Claude did so when they surveyed the system next day, it was not very long. At the lake we blew up our two-man and one-man dinghies and found that it was about 150 feet to a shingle bank, then a smaller lake led to a long section of easy walking on pebbles and small rocks. Just before we reached another bend in the passage a series of gours cascaded down from the right. We climbed up them but found that they reached the roof about 50 feet back; near to the edge the gours were often 5 ft. deep, though not now containing any water. This was one of the only two sections of formations that we found in the entire system, which is very unusual for Turkish caves.

The next obstacle was another lake, in fact from here to the end we boated across ten flooded sections. The passage was not now so large, though still big enough to drive a couple of buses through; at the lakes the roof in some places came down as low as five or six feet. As we went deeper into the cave the floor began to change from pleasant shingle to rocks, then from rocks to large, smooth and slippery boulders; on more than one occasion we had narrow escapes from broken bones. Every now and again a large tree trunk would be jammed across the passage or stuck up in the roof, a reminder that the river as we now saw it was quite a different one at other times of the year.

After four hours of this same kind of passage we came to a big oxbow about 15 ft. above the level of the river, where we found many old but very fine stalactites and flowstone cascades. From here to the end is a 450 ft. through passage that gets steadily bigger until the exit is almost as large as the entrance. Our excitement at being the first people through was lessened slightly by finding that it was now dark and we could see nothing of our surroundings. On top of that there was quite a breeze which blew our lamps out every few paces.

Degirmenini Düdeni. (Map 3b, Survey, Length 1,070 ft.)

Early the following morning we set off to explore the second of the River Caves, situated about 600 yards from the exit of Korukini. The entrance, though big, is not so impressive, many large boulders blocking the bottom half, but once inside it is equally fine. At the first lake, about 250 feet in, the walls narrow to 15 feet apart; the lake can be by-passed by making a high level traverse along the left wall, then an easy descent to a shingle bank separating the first from the second lake. Dinghies are necessary here and we set off down this 70 ft. high passage to the distant corner, round a bend and into a large flooded chamber, through more passages, round more bends into a very wide section. Then suddenly after another bend we could see a green valley silhouetted in a black exit about 150 feet on, a magnificent sight. It was a tremendous finish to come out of these fine River Caves in a boat.

About 60 feet above and to one side of the exit we came across a small cave, “Suludere Cave”, which had been a Christian chapel of the fifth or sixth century A.D. On the walls were many coloured religious figures resembling those of the Goreme churches, but most of them had unfortunately been deliberately disfigured at a later date.

Kimyos Polje

From Degirmenini the water flows towards the Kimyos (pronounced Kimbos) polje, but in summer and autumn the river sinks into its bed about 2 miles away. During winter and spring it flows directly into the polje, filling it about two thirds full. We knew from the French that it contained two short caves but the area had only been very briefly explored and the dolines behind the polje not investigated at all. We camped at the south end of the polje on the verandah of a forester’s one roomed hut.

The sublime beauty and wildness of the surrounding country is almost impossible to describe. The light brown of the long narrow polje contrasts sharply with the dark green pine forests and the glaring white limestone of the encircling moun tains, the whole topped by the deep blue of a cloudless sky. On our second night at this camp we learnt also of the wildness of its animals; early in the morning, before daylight, a shepherd, cloaked in his enormous sheepskin rug, brought to the forester a sheep which had been horribly gashed on its rump. He hold us that wolves had killed and savaged some ten of his flock on the polje—and this not more than a mile from us.

Feyzullahin Düdeni. (Length 700 ft.)

This cave was one of the two discovered by the French in 1966. It is situated on the west side of Kimyos about half a mile from its southern end. The entrance is obvious, it stands out black against the white rock just below the winter water mark, about 8 ft. high. Inside, a large boulder strewn passage heads straight into the mountain and there is a liberal coating of mud on everything. Neither the character of the passage, which is depressing, nor its direction varies throughout its length; it finishes with a large impenetrable boulder choke beneath a doline. With all the mud and organic debris about the floor and on the walls it could almost be described as one heaving mass of insects, fungi and toads, in fact a haven for any Biospeleologist. The toads were green (Bufo Viridis) and we often found them very deep in the dark zones of caves, they did not seem to suffer any ill effect.

Büyük Düdeni. (Length 400 ft.)

This cave is the second of the French discoveries. It is on the same side of the polje as Feyzullahin, but a mile further north, A passage about 50 ft. long leads to a pool which can be by-passed by wading knee deep in mud. At the other side is a large chamber from the western corner of which a descending passage leads to another chamber filled with water and no way on. From the first chamber another passage opposite the pool leads, via a muddy crawl, back to a sink in the surface of the polje.

After this we made a tour round the 22 mile perimeter of the polje in Michel’s car, but without success. We did however pass a tribe of nomad Yiiriiks complete with dromedaries and shaggy dogs. Michel told us that only five days before a similar tribe in the Eynif Polje not far away had an argument with some villagers and finished by attacking the village, killing several people and injuring many more, eventually the army had to be called in to restore order.

The dolines were next on our list and we spent a day investigating all those behind an area lying between Feyzullahin and Biiyiik but again with no success.

Sugla Lake Area

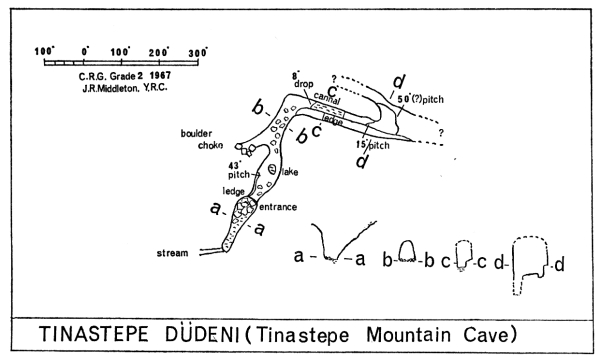

Tinastepe Düdeni. (Map 5, Survey).

The mountains in which this cave lies can actually be seen from the village of Cevizli, about 15 miles away, but to get there it is necessary to make a 70 mile detour via Beysehir and Seydisehir. The track into the mountains is a dirt one and leads to the Mortas Bauxite Mine, a new mine which has the largest potential for bauxite yet discovered in the world. The dam at Homa is being built primarily to provide electricity for this mine. About a mile from Mortas the road passes through an area of fantastic Lapiez containing many open and

unexplored shafts going down into the hundreds of feet.

About four miles on, at the end of the Tinastepe Polje is what must be one of the most impressive cave entrances in the world. It is at the base of a 500 ft. cliff and the river from the polje has cut a broad path in the limestone and under a 30 ft. wide rock bridge into a large amphitheatre where the water drops fifteeen feet into a lake. The way down for us was by traversing round under the cliff, past two smaller caves which showed signs of occupation, and into the amphitheatre. At the entrance to the cave, which is 25 ft. wide and 40 ft. high, the water drops down a 50 ft. pitch but we found that our best way was to traverse round a ledge on the left hand side until we could make an easy 43 ft. descent. Continuing into the cave past a lake a passage comes in from the left which finishes in a boulder choke; the main passage then makes an abrupt turn right and splits into two levels. The right half is a 4 ft. climb on to a ledge which starts flat and then slopes alarmingly as it gets above a drop estimated at 70 ft.; eventually it peters out. The left half drops 8 ft. into a canal which is not long but a dinghy was needed. This leads to a 15 ft. pitch on to a ledge with an estimated 50 ft. pitch. To the left of the ledge another large passage joins the main one.

Due to lack of time this was the limit of our exploration. There are two schools of thought as to where the water goes, one says into Sugla Lake, making a drop of 1,680 ft., while the other thinks that it resurges in the sea, a drop of 5,100 ft. Either way the big passage promises a fine system.

Back to Dumanli

For our last week we decided to revisit Dumanli. Whilst we only found one cave worthy of mention we did absolutely convince ourselves that there is not, at the Homa end, anyway, another entrance to Dumanli.

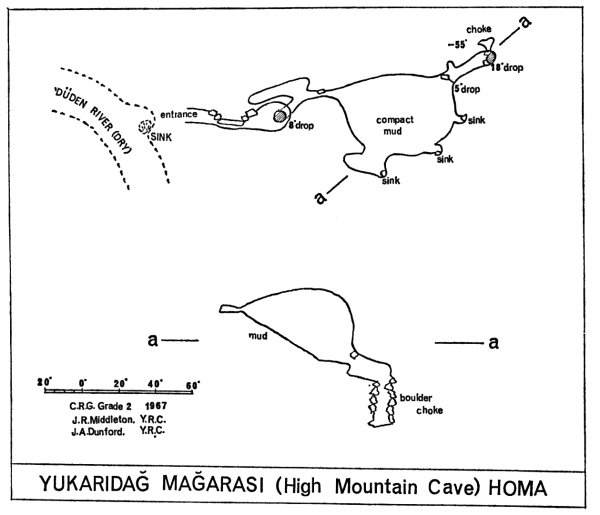

Yukaridag Magarasi. (Map 1, Survey)

This cave entrance had been seen and noted the previous year by one of the Turkish geologists. It is about two thirds of a mile upstream from Diiden Cave on a bend shortly after a smaller river joins the Diiden River. The entrance porch is about 8 ft. square and is 6 ft. above the present choked sink in the stream bed. After the entrance there is a squeeze past a fallen block into a low chamber in the centre of which is an 8 ft. climbable drop into a short passage joining another from the direction of the stream. This main passage goes on down to a small boulder choke, easily passed into a chamber some 40 ft. across and 25 ft. high with a mud floor ascending steeply to the right. Following the downward trend there is a 5 ft. drop over a boulder, a short passage and a further choke but it is possible to go down through the boulders for 18 feet to a mud sink. A squeeze back through the rocks at the bottom leads to some fine mud formations. In the main chamber we climbed up the mud slope and investigated two small sinks which dropped about 4 ft. At the top of the chamber is another sink in a low section but the mud here is very hard and dry, obviously it never floods as high as this.

Other Known Caves of Interest

Düden Cave. (Map 1)

This cave was explored by the French in 1966. It is about two miles up the Diiden Creek from the village of Homa. At this point the river runs along the boundary between the impermeable Miocene marls and the Mesozoic (Tertiary) limestone. The cave is on the limestone edge of the dry river bed, it appears as a 12 ft. climb down between boulders and a rock wall. Its hydrology is particularly interesting: in late summer and autumn it is a dry pot; in winter it is the finish of the stream, for the water of which it acts as a sink; in spring it is a flooded pot with the water flowing to the village of Homa; in early summer it is the start of a stream since it continues to be fed underground from the snow melting up in the mountains.

Scupidu. (Map 1)

This cave was discovered by the English party of 1966 and was broken into by an exploratory adit (R.A.3) on the left hand side of the first gorge, where the dam is to be built. Entry is made half way along the adit down a steeply descending fissure, well encrusted with flowstone and occasional formations. The descent is for about 35 ft. to a medium sized chamber containing a deep pool and upstream siphon. This was dived by Jeanmaire and Gilbert into a narrow passage and chamber leading to a further, impenetrable, siphon.

Tekepli. (Map 1)

A pothole discovered by the Turks in 1966. In a series of pitches a depth of 300 ft. was reached. The pot still goes down a pitch estimated at 100 ft.

Besidag Cave. (Map 1)

An old abandoned resurgence cave of no great length. Important because of its presumed past connection with the Dumanli underground river.

Karanlik Derlsi Cave. (Map 1)

Small well encrusted cave near to the River Manavgat.

Handos Cave. (Map 1)

Vauclusian spring which brings much water to the Manavgat River in spring. In late summer it can be descended for 50 ft. to a siphon.

Cayrönü Pot. (Map 2)

Discovered by the French in 1966 and explored to a depth of 410 ft. in a very fine and sporting system. Also visited by the English party.

Acknowledgements

I cannot finish this account without expressing my most sincere thanks to Dr. Aygen, without whose help and advice in both years our success with new finds would not have been possible. Our thanks are also due to the entomologists Michel and Annee Bakalowicz, who were our constant companions both above and below ground.

Notes on the Area Plans

- The basic outlines of the maps were taken from the following sheets—1:500,000 1963 Geological Map (Konya) 1:100,000 1946 Map (Beysehir 107-4, Antalya 124-2, Konya 108-3, Alanya 125-1). These are the largest scale maps available to the general public.

- The names of the villages on the 1:100,000 map are usually the old Arabic names, which are now rarely used. All the villages that we actually passed through and certainly all those near to the caves and potholes are correct, as amended to their modern usage by me.

- The only tracks which are marked on my plans are ones that we actually traversed or have been corrected by Dr. Aygen. The 1:100,000 edition cannot be relied upon for any of its tracks.

- All caves and potholes have been positioned accurately after reference to Dr. Aygen’s work, to the British Speleological Expedition to Turkey, 1966 report and to my own notes. It is essential to take into consideration that for actual field location these maps are on a small scale and are therefore intended for use primarily with my notes.

References to the Area

As Turkey is only a speleological playground in the making, there is as yet very little literature on the subject. The Turkish Speleological Society intends to bring out its first publication sometime in 1968 but until this appears the references listed below are all that I could find in an extensive search of Belgian, French, Turkish and English books and journals.

| Aygen, T. | An invitation to French Cavers, Spelunca No. 1, 1966, page 77. Bulletin de la Fédération Française de Spéléologie). |

| Aygen, T. | The Geological, Hydrogeological and Karstic Studies made in Manavgat—Oymapinar (Homa) Arch Dam Site, Beysehir—Sugla Lake and in Manavgat River Basin. Personal Publication, 1967. |

| Aygen, T. | Pictorial Reference to the above Report. 1967. |

| Bakalowicz, M. | Results of the 1966 Turkish Expedition by the Spéléo Club de la Faculté des Sciences d’Orsay. Grottes et Gouffres, No. 40, 1967. |

| Chabert, C. | Turkish Speleological Expedition, Grottes et Gouffres, No. 36, 1965. (Bulletin. Spéléo Club de Paris). |

| Chabert, C. | Turkish Speleological Expedition, Grottes et Gouffres, No. 38, 1966. |

| Chabert, C. | Turkish Letter (account of 1967 exploration) Grottes et Gouffres, No. 40, 1967. |

| Dunford, A. J. & Gilbert, T. | The British Speleological Expedition to Turkey. Exploration ’66, 1966 (Journal of Nottingham University) |

| Walker, M. | Turkish Cave References, 1965. Journal of the Oxford University Cave Club. |

In addition to the above there are many geological reports and papers on the area; the most important seem to be those written by a Frenchman, Monsieur Blumenthal, and by Dr. Aygen.