The British Speleological Expedition To Turkey, 1966

by J. R. Middleton

To the speleologist Turkey is a tremendous challenge with its great masses of unexplored cave-forming limestone. This, combined with the fact that it is somewhere different, encouraged Tony Dunford and Tim Gilbert to get in touch with Dr. Temucin Aygen, the President of the Turkish Speleological Society, and to ask if he could recommend any particular area should they visit his country. Dr. Aygen’s reply was most helpful: if they could come towards the end of July 1966 he would himself join the party and show them round. Possibilities now seemed so promising that it was decided to arrange an Expedition, of which I was privileged to be a member.

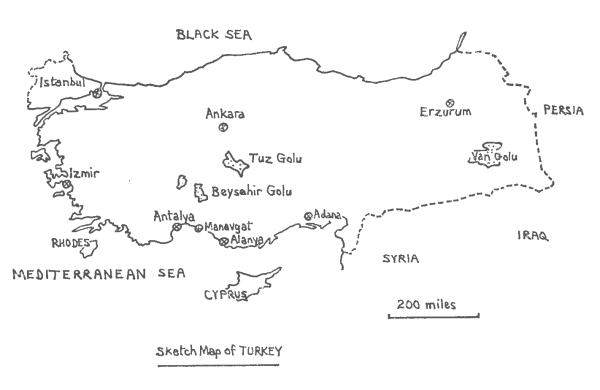

The area suggested was to the east of Antalya in the Western Taurus mountains. Exploration proved more difficult than expected, not because of the terrain, which was difficult anyway, but because of the intense heat which could beat down at anything up to 130°F. Snakes and scorpions provided an additional hazard and although we did not see many we were always aware that they were about.

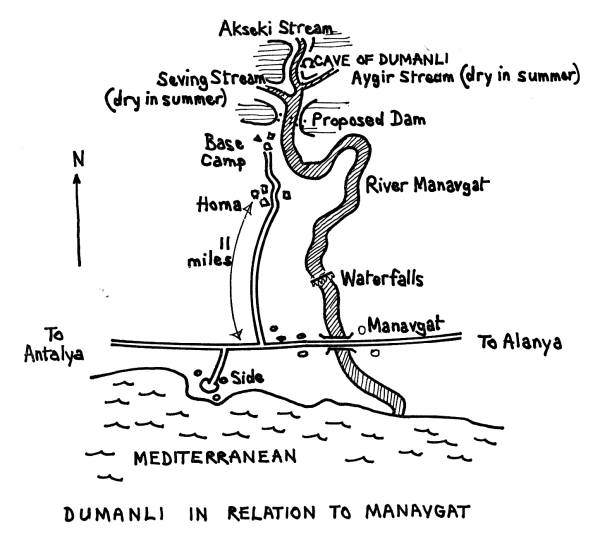

Our main objective was the resurgence of Dumanli about 20 miles up the River Manavgat from the Mediterranean coast. Our base was at the camp of the Turkish Electricity Company, who were building a dam there as part of a hydroelectric scheme. The resurgence was two miles further upstream, some 200 yards into a large gorge. Here, with tremendous vigour, spews out about one third of the water making up the River Manavgat. This water is thought by Turkish geologists to come from Beysehir Golu, over 50 miles in a straight line northwards, but this is still a very debatable point.

The T.E.C. wanted us to explore Dumanli and so, through Dr. Aygen who is also their chief geologist, they gave us all the help we needed. Because the gorge was impenetrable they were blasting a tunnel to a small beach opposite the resurgence, but this had not been finished when we first arrived at our base camp so Dr. Aygen took us for a few days into the mountains around Akseki, about 35 miles further north.

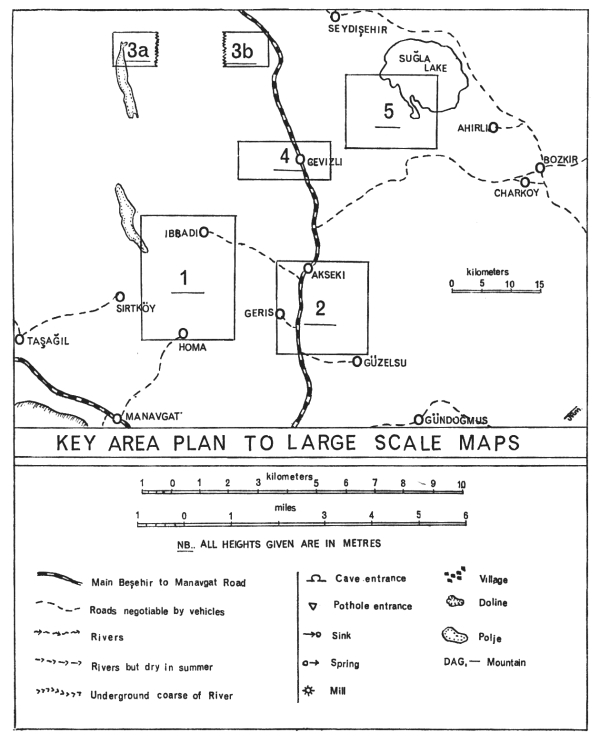

Caves of the Akseki Region

Around Akseki and in particular at Giiselsu and Dikman, with the help of the villagers and on occasion of their donkeys, we found and explored many large shafts and two deep cave systems. In the mountains above Dikman was a hole formed along a fault line, 400 yards long, 100 yards wide and 450 feet deep; two of our members descended this but could find no extensions.

Kelebekli—The Cave of the Butterfly. (Map 2)

On the way we stopped for refreshment in the small village of Topraktepe where we were told of a cave entrance barely 50 yards from the main road several miles further on. We found it easily, the entrance by English cave standards was quite large, measuring 8 feet high and 6 feet wide. Still wearing shorts and thin shirts and carrying our lamps and helmets, we jumped out of the back of the expedition lorry and raced for the dark coolness.

Twenty feet inside the cave the walls narrowed and the floor rose, making stooping inevitable for a short distance. Then the floor fell away steeply for 20 feet to a low but fairly wide and waterworn passage which soon rose into an aven about 30 feet high with several higher level passages leading off. As we wanted to be at our camping place by nightfall these possibilities were not explored and we continued on downwards, through a wondrously cool knee-deep pool, along a passage with razor-sharp edges and on to the top of a 15 foot pitch which we found climbable. At the bottom was a small high chamber, then a further 20 foot pitch, also climbable and finishing in a high chamber with a passage leading to what can well be described as a typical English sump which defied all attempts to dive it.

Guversin Orogu—The Cave of the Pigeon. (Map 2)

Our base was beside a well, a quarter of a mile from the village of Sadiklar on the road to Gtizelsu. Our primary objective was the descent of a deep shaft noted by the French cavers from Orsay University who joined us for the first week of our stay.

The entrance was on a ledge almost at the bottom of a hill only 100 yards from the camp; it was 15 feet in diameter and roughly circular in shape. Down the first pitch stones seemed to fall for a horrifyingly long way, so after putting 300 feet of ladder down we suggested that one of the French descend first as it was they who had found it. Jean-Pierre was the willing volunteer and started down taking one of our Transceivers with him. This new method of communication proved far better than any telephone system I have seen tried before, and with only a tenth of the trouble. At the bottom of the ladder Jean-Pierre tuned in to say that a solid floor was not yet in sight but that it was a very fine climb and that the walls were now in places covered with calcite. We lowered him two more ladders, sixty feet in all, and after fastening these on he continued placing foot beneath foot until he touched sloping ground at a depth of 350 feet. He was now in a fair sized chamber with quite a few large stalagmites. Tony Dunford went down only to learn on arrival at the bottom that all extensions were choked and he might as well go back up. It was as well that the climb proved to be comparatively easy.

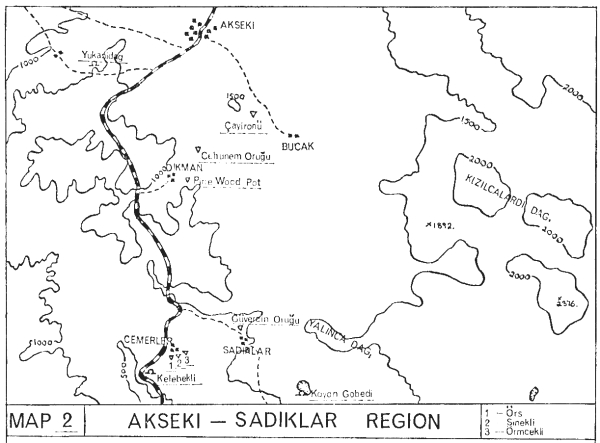

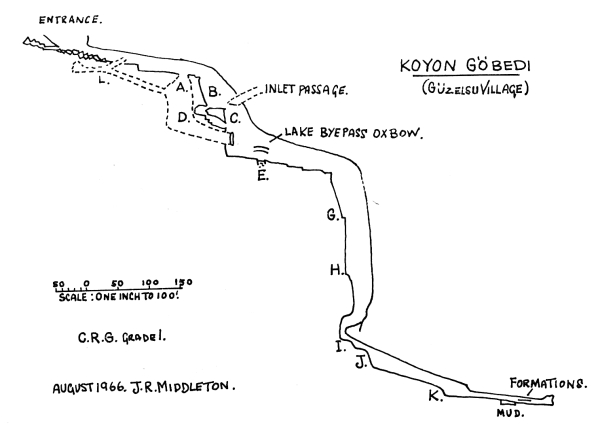

Koyon Göbedi—The Cave of the Lake of the Sheep (Map 2 and Survey)

The day after our descent of Guversin Orugu the villagers told us of a further hole, this time a large cave up in the hills. The French and two of our party went off to explore another hole found by Dr. Aygen near Akseki and whilst the others were tidying up the camp Tim Gilbert, a Turk, Christine and I followed a villager for an hour’s climbing walk to a valley about one mile across completely enclosed by mountains and with the valley floor sloping towards one big cave entrance. I should perhaps explain that Christine was one of the French party from Orsay and perhaps the most beautiful and proficient female speleologist I have ever caved with.

We quickly donned swimming trunks and boiler suits outside the opening and only 100 feet into the cave we found a 15 ft. pitch with a pool at the bottom. However, instead of using one of our three ladders we searched around for another way down and eventually found a chimney leading to a ledge which took us to the new passage level of even more abundant proportions than the entrance. We hurried on round a corner to find a large chamber with a steeply sloping drop. Looking back for an easy way down we found another pitch (A), but this was even deeper than the one which we first faced (B), so down this one we went using a 30 ft. ladder, a 15 ft. hand-line down an easy bit and then climbing the last ten feet. The passage now turned left and fifty feet further on, to our dismay, was a pitch of at least 80 ft. (C). By doing a short but airy traverse we moved into a wide inlet passage which we followed upwards for a short distance until we realised that it was taking us up instead of down. We again doubled back and found a 4 ft. high by 18 inch wide hole (D) leading from the bottom of pitch (A) and to one side of it. Immediately through the hole was a 15 ft. drop, but by traversing along we reached a small boulder chamber and climbed down the rocks; then back under the pitch and on down two small drops until we came out halfway down pitch (C). Our two ladders would now reach the bottom as it was only 45 ft. deep. Fifteen feet down this and to one side a high wide passage from pitch (A) came in.

From the bottom a 15 ft. wide and very high avenue continued to a 4 ft. vertical drop into a pool of unknown depth (E). We gradually lowered our sweating bodies into the 50°F water, enjoying the sensation as it slowly soaked into boots, crept over ankles, knees, thighs, stomach and eventually chest as we landed on a protrudiig rock. All around us was deeper water but by doing a hand traverse round the wall we reached the opposite side, 20 feet away, keeping head and shoulders dry. We later found a dry way round but it was very tight and rather muddy. Climbing out, by now cold and rather bedraggled, we found ourselves in a fairyland of a gallery, 15 ft. wide with its walls very smooth and of a light coloured limestone, occasionally calcite flowstone would cascade from the roof 30 ft. above our heads. The floor was one complete sheet of yellowish white flowstone vanishing into the distance. We went on through crystal clear pools, slid down calcite slides and finally arrived at the top of another pitch some 40 ft. across. This, apart from the top 20 ft., appeared to be in the form of a steeply descending calcite slope down which the stones we threw fell for an estimated 250 ft.

We hastened back to camp arriving in next to no time and hardly noticing the sun which beat down on us at around 125°F, to rouse the others into action. With a party now consisting of seven we renewed our attack by dropping a 30 ft. ladder down a gully to a ledge, then belaying a rope to the bottom, going down an 80° slope until it became vertical and finally swinging across to a convenient ledge (G), about 60 ft. below the ladder bottom. At the end of this ledge was a perfect belay point so here we hung 90 ft. more of ladder; the shaft was still large, some 30 ft. wide and 25 ft. across. Onwards down this fascinating flowstone pitch the ladder just reached a ledge (H), where a 15 ft. handline scramble took us to the edge of a further continuation of the shaft, this time a drop of 60 ft., the latter half of which was free hanging. The final section went off at right angles to the rest of this mammoth pitch down a final one of 12 ft. into a high but only 4 ft. wide passage (I). Through a pool and round a bend a much wider section fell away down a steep slope making another slide.

After a further 40 feet of walking came another pitch (J), which might have been climbed as a chimney but was easier on 30 ft. of electron. A gentle slope in the large passage at the bottom gradually became steeper until it finished in a 10 ft. vertical and unclimbable section (K). This dropped us into a rather forbidding passage containing mud, jammed tree trunks and other debris signifying a sump or impassable constriction at any moment. Suddenly a wall showed up in front of us—this must surely be the end—but no, a 10 ft. high and 8 ft. wide mud covered passage went off at right angles. This gradually became narrower until at a further 90° bend it was only 2 feet wide. Then came a muddy pool, climbing up to a ledge we traversed over it and into an upper passage where we found our first formations, mud-covered stalactites and stalagmites. This became too narrow so, dropping back to the floor of the main passage, we reached a small chamber where the shingle stretched up to the roof.

On the way out I crawled into a small passage near to the entrance (L), which led to a larger cross passage. Downwards this emerged at a point halfway down pitch (A); upwards was another short crawl into a small but well decorated chamber whose floor was littered with beetle cases, moth and butterfly wings and numerous other parts of insects. In several places were clusters of \ inch diameter clear eggs. My mind raced. Do scorpions lay eggs? Are snakes’ eggs like this? What about giant spiders? I beat a hasty and undignified retreat. Later, in camp, one of the French suggested that they might have been lizard eggs.

Pine Wood Pot. (Map 2)

From Giiselsu we moved to another hamlet, Dikman, where the villagers enthusiastically pointed out literally dozens of holes. We investigated several of these and found them to be all between 30 ft. and 80 ft. deep and usually choked at the bottom, but often with fine incrustations.

One worthy of mention was a shaft in a pine copse about half a mile from the village. The entrance was covered, possibly by the villagers, with large boulders but with just enough room for John Higgs to squeeze through. The climb was down a shaft of 120 ft. on to the top of a boulder slope at the bottom of which were two passages, but both were choked after a short distance. Just as John reached the top on his return he knocked off his carbide lamp, so Tim Gilbert volunteered to go and fetch it. On arriving at the bottom he found something that John had missed, a rather large and violently hissing snake: needless to say his ascent of the ladder was done in record time.

Ceheunem Orugu.—Hell Hole. (Map 2)

Next day five of us headed off into the mountains with pack donkey and village guide, arriving at the hole an hour and a half later practically shrivelled up by the sun. After refreshing ourselves from a well infested with live and dead beetles we summoned up the energy to drop 260 ft. of ladder over the edge of a very impressive hole some 20 ft. long and 8 ft. wide. The ladder hung free after the first 20 ft. and just touched bottom in an immense chamber. As usual there were some passages leading off but all proved choked; the few formations were very fine. An owl which had made the hole its home objected to our visit and dive bombed us most of the time.

We were in the Akseki area for five days; if the expedition had spent the whole of its time there I believe we would still have found plenty to do. As it was, apart from our own discoveries, the French made several others including one of over 500 feet in depth.

The Siege of Dumanli

As soon as the tunnel was finished a team of cavers consisting of 8 British, 4 French, 2 Turks and Dr. Aygen, with a dozen porters, attacked Dumanli for two weeks, gradually wresting from the mountain several maybe small but none the less impressive secrets.

The tunnel debouched upon a beach opposite the resurgence but owing to rapids we could not cross at this point, we had to go 20 yards upstream to where the river was wider and more or less ‘unfoaming’, though still moving swiftly. It took us two days’ work to get over and to find an effective method of getting men and equipment across. Eventually we devised an endless rope system with a 6-man dinghy fastened in the middle; even with this we could only send one man over at a time, two-man dinghies upset when about three yards out.

Once across we made our way over small boulder-covered resurgences to Dumanli; there was not one of the party who did not have his breath taken away by the magnificence of this impressive but somewhat frightening flow of violently bubbling water. The entrance is 20 ft. wide and 15 ft. high with the roof arching down to meet the water 20 feet into the cave. The river filled the whole entrance and was of unplumbable depth, but it did foam over a lip, at which point it was three feet deep; it then plunged over several more ledges to the main river 15 ft. below. For anyone to have fallen in here would have meant almost certain death.

Our first task was to see if the dominating fossil entance 100 ft. above the stream did actually go in and, if so, would it lead down to the Dumanli river? This job we left to the Speleological Society of Paris, who joined us for the last two weeks of our stay: they were better equipped for pegging a route up the cave entrance and on upwards to the fossil mouth. We crossed our fingers as the French gradually moved out of sight and into the shadow of the entrance, but it was of no avail, the floor quickly met the roof with no possible extensions.

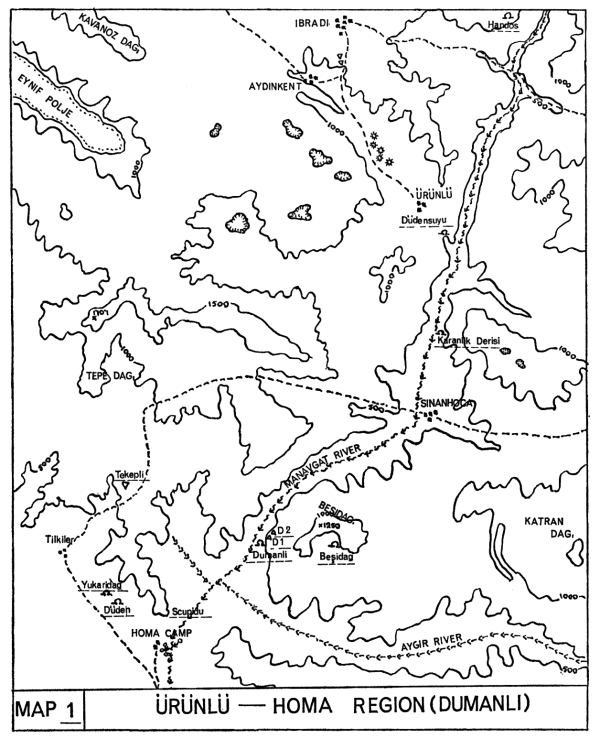

Dumanli 1. (Map 1)

The following day we split into twos and began to search for another entrance. Mike Clark and I hacked our way through undergrowth for an energetic twenty minutes up a narrow, steep and jungle-clad cleft about 50 yards upstream from Dumanli. At a point some 100 ft. above the river we were suddenly spurred into even more energetic action by the feel of a cold draught. Sure enough, 30 ft. higher up was an entrance 8 ft. high and 5 ft. wide with the thundering sound of water coming from inside. The floor immediately dropped down a short slope and then fell free for about 70 feet. By going half way down the slope and traversing we got to a broad recessed ledge from which we could look out into an enormous chamber. Having no ladder with us we searched for a way to climb down and found a low passage leading to an equally low chamber, one side of which looked out on the pitch while from the opposite wall a narrow crawl led us between beautifully calcified walls until after 30 feet it became too tight. As we could find no alternative to the pitch we returned to where the ladders had been left by the dinghy.

We hung the ladders, went down into a great chamber and on downwards to where the sound of water came from. To our disappointment, for we had no more ladder, we found a further 20 ft. pitch so we set about looking for another way down. We went first into an encrusted rift which became too narrow, then, on the opposite side behind a rock projection we found a 45° shingle slope the bottom 10 feet of which was a chimney climb, this landed us on a wide ridge between two rivers. The left hand one, looking forward, was 6 ft. wide, very deep and vanished into the distance round a bend—no good without a boat. The one on the right, about 15 feet away, was at a lower level, roaring and foaming its way into a siphon. So fast and wild was this river that at first we found it difficult to decide which way it flowed. It came out of a 5 ft. wide rift, later found to be over 100 ft. high, whose sides dropped sheer into the water. Several hand and foot holds appeared around the water level but as we had never met anything like this before we went back to explore the other river first. We tried a high level traverse but it did not go.

Just as we got back down again the French arrived with a dinghy, a remarkable affair, ideal for cave exploration, long and thin with a built-in air pump which was very effective. With two men in it, the dinghy proceeded down the left hand passage for 40 feet to a junction which we on the ledge could not see. A very fast flow of water came from under the rock wall to the left, crossed our stream and went down another high rift passage. Mostly by the water flow and partly by choice they went down here to a jammed boulder across the passage. Climbing on to this they found a higher level route leading off, this proved quite extensive but not of great importance. They managed to get back to the junction and then went further upstream but soon the walls came together bringing this section to a dead end. As it was getting late we welcomed the opportunity to leave the traverse along the right hand river until the morrow.

Five of us as explorers, with three surveyors, returned next day. We immediately began the traverse with Tim leading and laying a handline, unnecessary in actual fact as there were ample holds, though with the wild river constantly licking at our feet it was of psychological help. After the first 30 feet we could bridge the river for the next 40 feet which took us to the main Dumanli stream, about a quarter of which flowed down our passage. At this junction we were checked as the rock was all worn under and it was of course impossible to get into the river. Eventually we pegged a way up and along the left hand wall and dropped a ladder down to a boulder which spanned the upstream passage. As I was lifeliner I had to stay on a rather precarious ledge at the junction whilst Tony, Tim and John Ives made their way across. From the boulder they first tried upstream but once again after only 40 feet the walls came together. After a further two hours of downstream exploration we could find no more extensions so we had to go back to scouring the hills.

Dumanli 2. (Map 1)

Twelve hours later Tony and I again started up a densely wooded slope in the hope of finding another way in. When about 100 feet up we cut across horizontally and within five minutes we came upon a big boulder with a 30 ft. pitch behind it and the feel of a cold draught. We later found that this hole had been noted by two others but dismissed as not interesting. As we had no ladder we went on at the same level to see if we could find any more holes. We explored three small caves then, after a blank three hours, we found ourselves in a large cave entrance well up a 700 ft. cliff. The cave, which had fine formations, only went in for 50 feet, but the view from the entrance was really something. Imagine being 600 feet above a narrow gorge filled with rapids down which one could look to its end perhaps a mile away, then across a shrub-covered plain to another gorge of equally impressive proportions; all this through a thin lace curtain of hanging creepers and ferns.

Anyway, we then collected 30 feet of ladder, went back to the first hole and descended into the most welcome cool. The passage sloped down rapidly to a rift in the floor 6 ft. long and 18 inches wide. To the right of this was a magnificent calcite flow with a 12 ft. stalactite and stalagmite joined together. Across the rift a loose slope went upwards for 20 ft. into a massive and apparently bottomless chamber about 100 ft. in diameter with a high wide rift going away to the right. We rolled stones down the very loose slope in front of us and 50 ft. below us they suddenly dropped clear into water about 100 ft. below that. Excitedly we again dashed back to fetch ladder but found that time was getting on so we left exploration until next day.

On the following morning, which was my last, four of us, amply armed with ropes and ladders, cursed and sweated our way to the entrance, climbed quickly down the pitch, up the loose slope, and took stock of our surroundings. We were on the top of a pile of very loose rubble and dirt which, if we could find a way round, it would be best not to descend. Our first idea was to go down the fissure near the entrance pitch; we laddered the 20 ft. pitch and went down a steep calcite flow to several small but beautiful chambers with no outlet; so back to the top of the scree slope. We then traversed across and down to the right of the slope to the wall and found a small chamber amply decorated in black, red and white formations, well out of the way of loose rocks which we could not help knocking into the depths when crossing the slope.

From the chamber was a 10 ft. hand-line pitch to a ledge overlooking the big shaft. However it was still not advisable to go down here because of all the loose stuff above, so looking behind us we found a passage going back underneath to a 20 ft. climb down calcite flows using stumpy stalagmites as footholds. This landed us on a flowstone covered bridge with a 15 ft. glistening white column at one end; using this as a belay point we dropped three thirty foot ladders down a cal-cited wall: it really was a fantastically beautiful place. The ladders just reached the bottom, so John Ives and I descended to the edge of a further 20 ft. drop: we would need another ladder and dinghy. While one man went back for these John and I explored a gour filled passage to what we both thought was the most beautiful grotto we had either of us seen. We were awakened from our reverie by somebody shouting “Below!”; our equipment was being lowered down the wall. We inflated the dinghy, clipped the ladder on to the others and went down to find that the last 10 feet hung free into the water and we should have to get directly off the ladder into the boat. This was made all the more difficult by the current which, although it hardly made any noise was none the less powerful.

Upstream from the ladder was a most magnificent siphon, half-moon shaped, perhaps 30 feet round. Fifty feet downstream a projection of rock necessitated our getting out and re-launching but after a further 20 feet the passage narrowed; we had to fasten the dinghy up and continue by traversing, delicate in places, for 80 feet till the walls became too close to allow any more progress: beaten again but not disappointed. Dumanli was certainly very reluctant to give up her secrets but when she did they were well worth fighting for.

I now had to fly back to England as my time was up but the others still had ten days to go. Until their last two days no more big discoveries were made, then a large resurgence cave, Diidensuyu, was found further up the gorge, reached by a six hour road drive. This consisted of boating across tremendous lakes, climbing up the sides of giant gours, then boating across more lakes in vast passages. Progress was made for about half a mile but lack of time meant that many possibilities were left unexplored; enough to generate enthusiasm for another visit in the near future.

| A. Dunford (Leader) | Nottingham University Caving Club |

| M. Clark (Chief Surveyor) | British Speleological Association |

| M. Jeanmaire | Cave Diving Group |

| C. Wilkinson | Nottingham University Caving Club |

| J. Higgs | Nottingham University Caving Club |

| J. Ives | Nottingham University Caving Club |

| T. Gilbert | Wessex Cave Club |

| M. Holland | Wessex Cave Club |

| R. Gannicot | Wessex Cave Club |

| J. R. Middleton | Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club |