Mountains, Beaches And Sunshine In Corsica

by A. Tallon

We had decided earlier in the year that this time we would go somewhere different. This was certainly different; I was spending my first night in Corsica. Having teamed up with three French students, we had eaten well and were now lying on the beach at Calvi in our sleeping bags. We had bathed in the Mediterranean and were relaxing on the warm sand under a clear starlit sky v/ith the music of the Calvi night spots just audible across the bay. The other two members of my party were due to arrive by air at Ajaccio next morning; I was due to meet them at Porto in the evening. Having had one encounter with the Corsican bus service I had serious doubts about this meeting ever taking place.

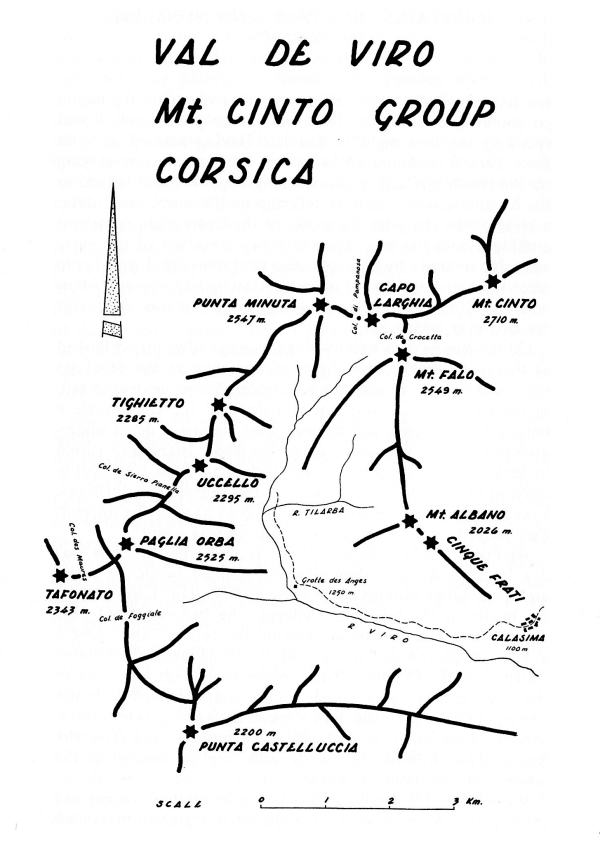

On the bus next morning—there was one after all—I looked at the rivers marked on the map and then at the dried up ravines they were in reality and wondered how we would fare in the mountains. It was hot and dry and the countryside a barren waste of rock and maquis. This maquis, a dense undergrowth of scrub, seemed to cover the whole island and varied in height from six inches to ten feet. Some that we encountered in the Val de Viro was several feet higher than ourselves. I could just see the mountains in the heat haze of the interior; they looked very impressive and a long way away.

At Porto I asked three different people when the bus was due in from Ajaccio; they all thought there would be a bus and gave times ranging from 6.30 to 8.00 p.m. I went up to the bridge at the top of the village—the bus could not pass through the village without crossing the bridge—and spent a a very pleasant hour and a half watching people collecting water from the fountain. The evening was warm and most of the water carriers were female and young; the ninety minutes passed quickly and the bus appeared carrying, along with several score other people, Albert Chapman and Timothy Smith. They looked very white and English among all the other sunburnt holiday makers.

We soon had the tent up next to the beach, had a meal and made plans. We were now a complete party and we marvelled at the wonders of modern travel and how Corsican buses and trains (we found out about the trains later) could exist in the same world as guided missiles and turbo-jet airliners. The next day we spent lying on the beach at Porto and swimming; Porto has a lovely but stony beach in a really striking situation. On the Monday afternoon we caught the bus for Cala-cuccia. We all admitted a slight reluctance to leave the beach with its bronzed bikini-clad beauties, but most of these lovely creatures were escorted by big brown Frenchmen carrying harpoon guns.

Calacuccia, reached after a very sporting three-hour bus ride over mountain passes, through fantastic gorges and pine and chestnut forests, was disappointing. Was this the famous centre of Corsican climbing? It looked a dirty, uninteresting town with poor camp sites and little running water. We moved on.

Our next stop was Calasima, four miles on the road to the Grotte des Anges, where we intended to make our base. At this point I must make a confession. We did not walk to Calasima—we took a taxi. There is a good new road as far as the village and the object of this very unmountaineering-like act was to gain time, as we wanted to push as far up the valley as possible that night. The camp site was a good one, about 1½ miles past Calasima on the track to the Grotte des Anges. It was, after all, good to be away from the crowded beaches; here we had pine forests, a clear stream with trout and pools for swimming, and above everything the peak of Paglia Orba, the most impressive mountain in the area.

Next morning, after a chat with a friendly shepherd, we were soon on our way again. It was hot and with 50 lb. rucksacks and sunburnt backs the dusty track seemed long. After one hour’s walking, and another hour’s resting we came upon the Grotte des Anges, a huge overhanging boulder forming a cave which, with its man-made walls around the exposed sides, made a very acceptable shelter from the sun and rain. Twenty yards away was the stream and the edge of the forest and after inspection of the surrounding area for better sites, and French generals in hiding after the Algerian revolt, we decided to make this our base. Here we had a flat place for the tent, a cave in which to rest and eat out of the sun and a river for water, swimming and perhaps even trout. We were near the mountains. Camping at its best.

In the afternoon we decided to walk up the valley and have a look around. We set off at one o’clock through the forest on a good forester’s track. Fir cones and Corsican pine seedlings littered the path; it was hot but not unpleasantly so in the shade of the trees; we quickly gained height and swung round to the right into a side valley leading up to Monte Falo. We were soon on the edge of the tree line and just above us was the ridge running south-west from Monte Falo. How deceptive is distance when one is anxious to see new country and climb new peaks. From the ridge the top of Monte Falo seemed but a short scramble away. Two and a half hours later we were still staggering upwards in the full glare of the sun and the short scramble had become an age of hot, dusty scree. We turned back about 200 ft. from the summit and were happy to get back to camp about 7.30 in the evening. We would somehow have to adapt our climbing to suit the conditions if we were to climb anything at all during the holiday; climb-ing in the middle of the day had proved to be almost impossible and extremely unpleasant. To climb Paglia Orba, which we intended to do next day, we would set off in the late afternoon with food and sleeping bags, travel in the comparative cool of the evening, sleep as high as possible and climb the peak in the early morning. So after preparing our plan and our evening meal we ate and felt more content.

The camping at the Grotte was ideal. We swam in the mornings when we were in camp, cooked our meals in the shade of the rock, and slept or went fishing when it was too hot to do anything else. There were small trout in the stream, we managed to catch three one afternoon but had no success otherwise. Midges and flying insects did not seem to bother us; there were ants in their thousands all over Corsica but they did not seem to bite; the Grotte was alive with lizards but they seemed harmless and quite friendly. Down by the stream the moths and butterflies were lovely.

Next evening at 5.30 we were off with food and sleeping bags for the Col de Foggiale (1963 metres), south of Paglia Orba. There was quite a good track up the valley and even after passing the bergerie (a collection of rough sheep folds and a shepherd’s hut with cows, goats and pigs wandering about) the track was fairly well cairned. We camped half an hour below the col when darkness overtook us about 8.30, at the base of some steep rock. It was a good bivouac site: the night was clear, the stars shone and the maquis we slept on was of the non-prickly variety. Although we were quite high (1,900 m.) we only just needed to put on sweaters before turning in. Our sleeping bags were rather too warm for sleeping in the valley.

We started next morning at 5.15 just after it became light and we were soon over the col and round towards the back of Paglia Orba. We went up a route given in the Club Alpin Franeais guide book as ‘one of the easiest and most interesting’. We were not a serious rock climbing party, perhaps not a serious party in any sense, and did not want to be involved in any hard climbing in hot weather in unknown country. The guide book gave an accurate description of the climb and the route was easy to follow; at only two places did we really need the rope. We climbed to the summit, which we reached at 8 a.m., in shade all the way. Tafonato is next door to Paglia Orba, joined to it by the Col de Maures and we had superb views of the Trou de Tafonato, a great hole through the mountain fairly low down which made Tafonato look like a huge bridge. We stayed for three-quarters of an hour on the summit (2,525 m.) and the sun was now strong. To the north east was the spiky ridge leading to Punta Minuta and Capo Larghia, with Monte Cinto far to the north, and Monte Falo, the scene of our setback on the first day, to the south of it. Away to the south was Monte d’Oro with patches of snow struggling vainly for survival in the blazing sun. On the way down we climbed a small peak to the south of the Col de Foggiale and we were not back in camp until 3.30 p.m. We were delayed partly by a swim in some pools which were almost perfect ellipses in shape but we were even more delayed by the heat of the early afternoon.

After another swim and a meal Chapman and I went down to Calasima for supplies, reaching the village after one hour’s walk down the valley. We were hot and tired so we walked into the first bar we saw and asked for a drink of orange. There, in the corner of this small bar in the highest village in Corsica, stood an Electrolux fridge and out of it came our orange drinks. After our drink we asked about buying supplies. One of the village children took us to the epicerie, it looked like a stable from the outside, and we bought our supplies, they even sold Gillette razor blades; the fruit van was in the village that evening and we bought melons, pears, oranges, grapes, greengages and potatoes, there was no bread until the next morning but the woman from the bar sold us one of her own loaves. We also bought two litres of wine from a woman we met at the epicerie for something like two shillings a litre. We had a good meal that evening. We liked Calasima and the people who lived there. On another visit the woman in charge of the epicerie was away but we were given what we wanted and told to pay later; a man invited us into his house for a glass (or two) of Cedratine, the Corsican liqueur: but what we liked most of all was the distinction the villagers made between ‘tourists’ and ‘alpinists’. When we got back to our camp site after our first visit Smith had a huge camp fire burning at the Grotte and was full of stories of scores of brigands, some riding mules but all carrying rifles who had marched past our camp shouting. He had been on his own long enough!

Next night we bivouacked in the Val de Viro and from there climbed Punta Minuta and Capo Rosso. This was a very special bivouac: it actually rained that night. There were about six drops just as we were about to get into our sleeping bags; we fled up the mountainside to the shelter of a small cave, but there was no need, the shower was over. Next morning we had a prolonged shower of about fifteen minutes and the day was fairly cloudy. We enjoyed climbing our two peaks and were back in camp by one o’clock to find that we had visitors. Two Oxford University men whom we had met in Porto had come up to see us and intended to spend the night at the Grotte. That evening we made another trip to Calasima and on the way back met a very strange creature on the track. It was lizard-like, about eight inches long, black and brilliant yellow in colour with a leopard-like head and slow deliberate movements. We had not had much Cedratine, only two glasses each, and we eventually established that this animal was in fact a Fire Salamander.

The next bivouac was again up in the Val de Viro, but this time much higher (2,100 m.) half an hour below the Col de Crocetta (2,300 m.). It was rather cold that night with heavy dew. We spent some time arguing about the position of the North Star and whether a certain star was a planet or somebody camping on the ridge of Monte Falo. We slept well, were up at 4.30 and away by 4.55; it was cold that morning but we were glad of it because the first half-hour up on the col was hard work on steep scree. From the col a fairly well cairned track led us to the summit of Monte Cinto at 6.45. A large party of French lads with huge hats and a local guide reached the summit from the Calacuccia side soon after us, the first party we had met at close quarters in the Corsican mountains. Monte Cinto at 2,700 m. is the highest mountain in Corsica and we were happy to have climbed it on this, our last day in the mountains. On the way back we avenged our set-back on the first day by climbing Monte Falo from the north. And that was the end of our climbing holiday: we had climbed four big mountains and two smaller ones, we had visited country new to us and we had been alone in the hills.

Next day we walked through Calasima to Calacuccia and camped there for the night. We met one of a party of Durham University students who were spending ten weeks in the area doing various sorts of research work. He told us something of the history and social life of the district. He also explained the mystery of several very striking blondes we had seen at Calasima along with the more usual Latin types. Nordic families had apparently settled in the area many years ago and in the isolated valleys these Nordic types are still produced. We had thought they were visiting film stars. But there was one thing which baffled both the students and ourselves; nobody in the interior of the island ever seemed to do any work; that is, no one except the postman, the taxi driver and the numerous bar keepers. Could they have some unknown source of income?

One other incident is worth relating: our encounter with the Corsican railway. We travelled from Corte to Calvi. The railways in Corsica have only a single track except at a few stations where trains can pass. We were delayed for about an hour at Corte because the train due in from the other direction had not arrived (perhaps the driver had stopped to visit relatives or been delayed by a stubborn cow on the line, or possibly even by a forest fire). Our train had two carriages and was full, even by Corsican standards. About an hour out from the station we were waved down and there on the track ahead was another train. This sort of situation can be awkward on a single track, but in this case all was under control. We were asked to change trains. The passengers soon changed over but the baggage took longer. Eventually we were off again but at the next station the three of us had to change to another train for Calvi. This change was not on the time-table, neither had the other been, but we were assured that it was all right and off we went again; this time it seemed that the driver was determined to make up for lost time. We were sitting in the front of the train, a mistake, and we watched the driver put the engine in top gear, light a cigarette and go to sleep. We had an uninterrupted view of the lines disappearing round bends ahead of us. We slowed down sometimes to avoid a cow or a pig on the line and stopped at the odd derelict station to pick up passengers, sometimes we just stopped at the side of a road to let someone off and once we just stopped and a man got out and walked off into the maquis. It was dark when we reached Calvi; a case of travelling hopefully and arriving thankfully.

As a climbing holiday our visit to Corsica was well worthwhile. Perhaps another time it would be better to go in May or June when the beaches are less crowded and the temperature lower. We found the sun temperature to be over 125°F on several days, and the shade temperature over 90°F; it was 100°F in the tent before 8 a.m. on some days. The food at the hotels is fairly expensive and mostly very poor. One can camp almost anywhere but near the towns there are recognised camp sites, mostly without sanitation and some without water. Calasima is one of the least spoilt villages I have ever visited and here we met genuine friendship and help. The mountains are rock and the rock is good, the easy routes are interesting and the hard routes looked very hard.