Mount Arrowsmith — Vancouver Island

by H. P. Devenish

Canada has plenty of magnificent mountains to suit all tastes, but I have never had time or opportunity to do any serious climbing in the Rockies, Selkirks or Coast Range. Vancouver Island, where I live, has mountains running up to 7,000 feet or more, but nearly all are practically inaccessible. There is however one, Arrowsmith with its Siamese twin, Colclough, which relenting Nature has planted just off a main highway. Even so it is a worthy foe for it stands 5,958 feet high and, since the ascent begins near sea level and involves two long descents, the total climb cannot be less than 6,000 feet.

My companion was a young German of magnificent physique, and something of a poet and philosopher. We drove up to the mountain one evening, parked the car in a small wood just off the highway, spread our blankets on the ground and turned in.

Next morning we started at 4.30 while it was still quite dark. We followed a rough road for half a mile, and then the trail began, climbing in steep zig-zags up the tree-covered side of the mountain. After over an hour of this the gradient eased and the trail straightened out a little, leading back, still climbing, over the top of this first massif. It was now quite light, but very cold. Finally, nearly three hours from the start, we emerged from the trees on to a small plateau where lay the remains of a log cabin, erected many years ago for climbers, but neglected and abused until it fell to pieces. On the grass lay a neat row of bed rolls—we evidently had not the mountain to ourselves. Here for the first time we saw the sun, so took a few minutes’ rest.

At this point the trail changed its character, passing the tree-line and often leading over bare rocks, where the way was marked by small cairns. One or two patches of snow were passed, and soon we reached the foot of the great ridge of Colclough proper. The trail faded out and we scrambled up on rocks and heather as best we could, until our way was barred by a steep snow slope. Hans went at it where he met it, at its highest, kicking steps in its soft surface. At 28 you can do these things but at 58 you have to economise, so I made a short traverse to the right and cut my snow climb in half. Once past that we were on the crest of the ridge, which led by an easy gradient to the summit. Most people content themselves with this and say they have climbed Arrow-smith, but we were after the real thing and had no energy to spare for the cairn on Colclough. Instead we crossed the ridge and sat down for breakfast.

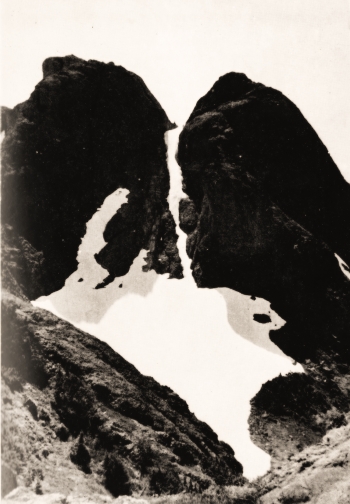

It was now eight o’clock, the sun was warm and we enjoyed perhaps the finest view of the whole climb. Below lay a huge remote hollow, covered with trees and floored by a tiny lake ; on the right was the mile-long undulating ridge which connects the two mountains, while straight in front the jagged silhouette of Arrowsmith stood up black and stark against the clear sky.

We were soon on the way again, and at once there came a sharp though easy descent down a rock gully, then a short ascent, then a really big descent, just steep enough to need the occasional use of hands. Later came a razor edged snow ridge, which could however be avoided by tramping through the heather below it, and finally a long hard pull up over earth, boulders and stunted trees. This landed us on the extreme end of Arrowsmith and, the peak being at the other end, we now had to traverse seven gendarmes in order to reach it. These were all good clean rock and presented no problems, though there was occasional slight exposure, and one descent needed care. As we progressed we heard a shout, and saw that the summit was dotted with figures.

Soon we topped the last knob but one, and there before us stood the last and greatest. Rather formidable it looked as it towered, apparently vertically, far above us. The lower part consisted of a steep and narrow ridge, sloping away sharply on either side to tremendous precipices. This broadened and steepened to a face of about 100 feet and then eased off quickly to the almost flat top. We descended to a tiny col, scrambled up a steep earth gully and emerged on to a grassy slope just below the rocks where we discarded our rucksacks and I changed into rubbers for the final assault. The rocks were warm and dry in the hot sun and we soon scrambled up to the foot of the climb proper. We climbed into a narrow chimney which split the face, went up it until stopped by an overhang, and traversed back on to the face by a broad ledge. A few more short pitches, all on good holds and the climb was over As we walked to the cairn we passed a deer’s hoof print, so there is evidently some other access.

In spite of slight haziness the view from the summit really was superb, on one side the Pacific sparkled in the midday sun, while on the other, over the black bulk of Colclough, stretched the Strait of Georgia, dotted with islands and backed by the tremendous screen of the Coast Range. Far below, to the north-west, lay the twin towns of Alberni and Port Alberni (Spanish names abound all along the coast), and beyond them showed peak after peak to the limit of vision.

We sat and sunned ourselves for a short while and then turned to the descent. This looked horrible, for a slip would obviously land you on that narrow ridge, where nothing could save you from rolling down and shooting off into space. However, the holds were universally good and the rock sound, so it did not take long to reach the grass. We made our way back over the bumps and down on to the ridge, until we reached a tiny stream. Here we flopped on to the heather and had a long rest, eating our lunch and drinking the delicious mountain water. Then we set off again, doing the rest of the descent non-stop and reaching the car at six o’clock, with several hours of daylight in hand.