NORWEGIAN HOLIDAY, 1950

By R. L. Holmes

The approach to the Jotunheim, the highest mountain area in the country, is one of the finest possible introductions to a holiday. From Bergen fast steamers sail up the great Sognefjord almost to the heart of the mountains themselves. Near the head of the fjord the steep sides close in, and spectacular precipices, often divided by cascading waterfalls, give promise of happy days to come. Up the northern branches of the fjord the glaciers of the Jostedal icefield brim over dark rock walls, gleaming brightly high above the shadowed water.

Leaving the steamer at Hermansverk, a five-hour bus journey leads to Turtagro, the climbing centre of the western Jotunheim. The road, twisting at first along the bottoms of dark valleys, then rises to run by blue lakes and swirling torrents. Dropping again to the fjord it skirts along the shore, at times on a bed blasted from the solid rock overhanging the water. At Skjolden the fjord is left behind and after passing through another deep valley the road hairpins up into the mountains.

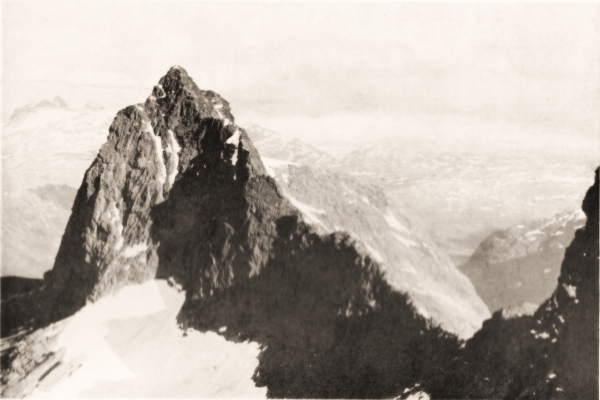

At Turtagro there is a good hotel, rich in associations of early days. Photographs of Slingsby and other climbers who did so much to open up the Norwegian mountains hang round the walls, and Fr. Berge, daughter of the famous Ole Berge is still in residence. From the windows can be seen the Skagastols ridge, leading up to the great cone of Skagastolstind, one of the finest, and certainly the most famous peak in the district. Two hours up from the hotel, on the col between Skagastolsdalen and Maradalen, is the Bandet Hut. This is a small draughty building, little used now except for the brewing of coffee before and after climbs. Bedding and food have to be carried up by anyone intending to stay there, but as a reward for this effort, it offers an excellent base for many longer expeditions.

The first two days of our stay at Turtagro were showery, and we saw little of the mountains except for a brief glimpse of black crags through a parting in the mist, but on the evening of the second day the sun broke through and we saw for the first time the array of pinnacles and ridges, dominated by Skagastolstind, with the tip of the fantastic Riingstind leaning above the nearer hills. Our expeditions 011 these first two days were modest explorations, keeping below the mist as much as possible ; but lured out by the improved weather, we set off on the morning of the third day on a longer excursion.

For the most part there is no need for early morning starts in Norway. The mountains are not high by Alpine standards, few summits rising above 8,000 ft. The days also are long, and since most of the hard climbing is on rock, with in general little danger from icefalls, 8 a.m. is a convenient time to set off on most routes. So on the third day we set off after an ample breakfast, packing our goat cheese sandwiches into our rucksacks along with the Karabiners and (a contribution from our Norwegian companion) a few pitons and a hammer.

We took the track up towards Bandet, our starting point on many days ; reaching the hut after about two hours’ steady climb we stopped for half an hour to brew coffee and eat a few sandwiches, until the cold drove us on our way. No matter how warm the day, twenty minutes in Bandet was always enough to chill.

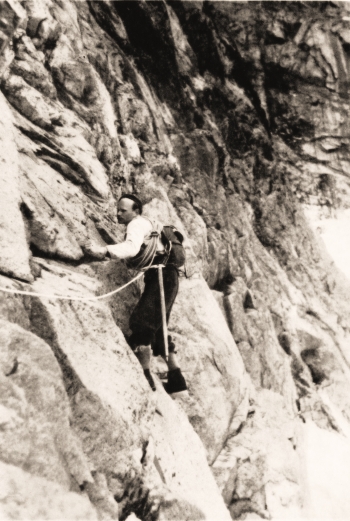

We started off down the Maradals glacier, roped now, and across towards the foot of the North Maradalstind, a summit on the dark ridge that we could see running down in the direction of Vettisfoss. Slowly we approached the black rock and as we came nearer our intended route became more obvious. The cliff ahead seemed no higher than the crags of Scafell, and less vertical. As the glacier steepened again towards the rock the higher part of the gully we were to follow was lost to our sight. At last we came to a small bergschrund at the foot of the gully and the route proper lay up and to the left. We climbed a tongue of snow and on to precarious trellises of ice, but there was no way there. We moved right again and found a slender snow bridge leading across to the foot of some steep iced rock. After some delay the leader managed to cross on to this and reached a small stance to which we followed. We climbed singly upwards ; the going was difficult, especially when we were forced left on to a thin traverse. Belays were almost non-existent and at the worst section we were thankful for the pitons.

After some 400 ft. of snow climbing we made another attempt to enter the gully proper where the true route lay. This was still impossible so we climbed directly upwards again on to smoother and steeper slabs, which soared for hundreds of feet above our heads. The few hours within which we had thought to reach the ridge had already passed, and still the rocks stretched above. But at last we came near to the gully again and were able to clamber across into it. The snow on its floor was soft and the deeper debris held together only loosely.

At length the ridge itself again came into view. The gully steepened ; I climbed up to the left and took a belay round a large boulder. Eric found a stance in the gully itself, some ten feet below, while Odd, the leader, climbed ahead. Suddenly he gave a shout. With a spurt of stones a great block on which he was standing shifted and began to slide downwards. Within a second Eric had swung on the rope, hurling himself out of the track of the rock. The leader pulled himself up on his hand hold while I預nd my belay揺eld fast. In a few seconds it was all over. The boulder rumbled down the gully and finally curved out to fall on to the glacier far below. Eric climbed up to a secure perch and Odd prepared to continue on his way. We were all somewhat shaken and climbed carefully over the rotten debris.

Half an hour later we reached the crest of the ridge. We stopped and ate a little dried fruit and a few sandwiches. Already the light was beginning to fade, and we shivered. Since we had reached the ridge hours later than we had intended we now sought the most direct way of descent. There were two alternatives ; either to traverse along the crest to Lavskar, which offered an easy way down to the Maradals glacier ; or to try and make a direct descent to the Riings glacier. We chose the latter for the way to Lavskar lay over the Pinnacles and we were in no mood for a prolonged ridge traverse. After an hour of cautious sorties and false hopes we found what appeared to be a fair means of descent預 gully falling, as far as we could see, direct to the glacier. We started down ; snow in the gully was soft and water dripped from the rocky walls, while the bed was of treacherously loose stones. We climbed slowly and carefully one at a time for the first few hundred feet. Time was going far too quickly ; we uncoiled our other rope and began to abseil wherever possible. The shadow of the Riingstind lengthened across the snow below and a deep blue colour tinged everything. Now we were wet, tired and hungry, and however carefully we moved it seemed impossible not to send a few small stones bouncing down towards the glacier, so that the leader was forced to seek a shelter as much as a belay after each pitch of his downward progress.

But at last the gully became shallow and we could climb out on to the clean rock. We moved on down, slowly still, but more safely ; another half hour and we were above the bergschrund at the foot of the rock ; a way over was found and we were again on the snow. Progress was better now; we moved together down the slope, at times glissading cautiously; slow over a bad patch of ice, then more quickly again over snow. At last we stood on the glacier and familiar ground for we had passed this way twice before. We made for the rocks on the right, passed across them and then down on to a fine snow slope leading to the foot of the ice.

The walk down the valley and across the rough ground to the hotel was a two hour plod. But once back we sat down to a fine meal, followed by coffee in front of the big white fireplace, with five candles flickering above it. Then we slept.

We spent several pleasant but less strenuous days at Turtagio. Then the weather broke on the tops and we set off to walk round the more easterly Jotunheim, leaving Skagastolstind still unclimbed. The eastern mountains are as high as the western group, but in general less spectacular and less favoured by climbers. For all that there are some fine days to be had here. The one we most enjoyed, one equal to any in the holiday, was the traverse of Galdhoppiggen by the glacier route, from Spiterstulen to Elversaeter.

From Elversaeter we returned to Turtagro, where fine weather once again favoured us. On our first day back there we climbed Skagastolstind by the ordinary route. The following day we set out again for the same peak, this time following Slingsby’s original way. From Bandet we traversed right, over on to the Slingsby glacier, which we had seen from some two thousand feet up on the previous day, on the last part of the Vigdals route. Now we stood on those waves of jagged ice which from above had seemed to rear up against the mountain at an impossible angle. But the going was good ; we held to the centre of the glacier at first, zigzagging between the crevasses and jumping the smaller ones ; then as we climbed we moved across towards its right hand edge. Near the top of the ice we halted for food, then climbed up over the rock on to the steep final snow leading to Mohn’s Skar. From the Skar we had an entirely new view of the mountain, and the last climb up the rocks to the summit made a worthy finish to the routeI think easily the finest approach to Skagastolstind.

A day or two later the weather broke again on the high ground and we decided to return to Bergen travelling by a way different from that by which we had come. We crossed the Sognefjord to Aurland預 town of shoemakers預nd from here walked to Finse on the Bergen涌slo railway, staying at Tourist Stations on the way. These are something of a cross between an hotel and a Youth Hostel, and are scattered about the country, each within a day’s walking distance of the next. Placed often many miles from the nearest road, many depend for all their supplies on pack-horse transport. Food and accommodation are usually excellent and cheap.

Our route lay through wooded valleys ; lakes and rivers of slaty blue water teemed with trout, not found in the higher glacial streams. The country was less rugged but strikingly colourful after the austere black and white of the mountains. At Bergen the big shops, the crowds, the fish market with tanks of live fish, and the busy harbour gave us more than enough to see in the day and a half we had before the boat sailed.

Norway leaves many impressions. The food is abundant and varied and is indeed a holiday in itself. Breakfast tables are hidden beneath a variety of cheeses, breads, fish and meats, making even the traditional English eggs and bacon appear a frugal meal; while in the evening, after a large dish of meat has passed several times round the table, one does well to sit quietly before a log fire, drinking coffee as the candles flicker over the white fireplace.