EDOUARD ALFRED MARTEL (1859-1938)

By The Editor

The great geographer, Edouard Martel, died in June, 1938 in his 79th year. He was an Honorary Member of the Alpine Club, of our Club since 1906, and was President of the Societe de Geographie, 1928-31, Membre du Conseil Superieure d’Hygiene, Administrateur du Touring Club.

The Editor naturally expected to draw on French magazines for an account of his career, but Spelunca is so sternly scientific that it appeared in 1939 (No. VIII.) without even a note of Martel’s death. A memoir was promised by La Geographie but nothing appeared up to the last number seen, May, 1939.

In La Montague (July, 1938) there is a memoir which is appreciative but vague, and contains a passage depreciatory of Martel as not having been a “bio-speleologist,” in other words a ” bug-hunter.” One might as well deplore that Whymper was not a ski-runner. The unfortunate thing is that the Alpine Journal notice was compressed from this into four paragraphs, one deplores his inadequate bug-hunting, one represents him as a tourist publicist and a writer on caves rather than an explorer, the last as a good teacher, a word not occurring in the French. I am afraid the phrase commonly used of Martel, ” The Master,” led the condenser on the wrong track in his free translation.

My impression is that Martel had outlived his contemporaries and that there was none who could write without research of his doings and career.

The man who dared to descend Gaping Gill without expert support, and to risk knots in his life line, who revealed the vastness and beauty underground in France, who proved the truth up to the hilt of what to-day seems obvious about limestone, who taught the French the difference between pure and poisonous water supply, deserves from some of his humble followers, an attempt at an adequate story.

E. A. Martel was born at Pontoise. He must have belonged to a well-to-do family as at seven years of age he was taken into the Caves of Gargas and Eaux Chaudes in the Pyrenees, and at twenty he visited the Adelsberg Cavern (now Postumia). His profession was law and from 1887 to 1899 he practised at the Paris Bar.

In 1883, ’84, ’85, wandering into every corner of the strange and wonderful district of the Causses, he met high above the gorges the yawning pot-holes, information about which came down merely to legend and superstition. In 1888 a visit to Han in Belgium fired him to tackle the abysses that had so impressed him. But in these early years of manhood he did much climbing in the Alps, for in 1895 he had travelled the Alps from end to end twelve times, and published with Lorria Massif de la Bernina.

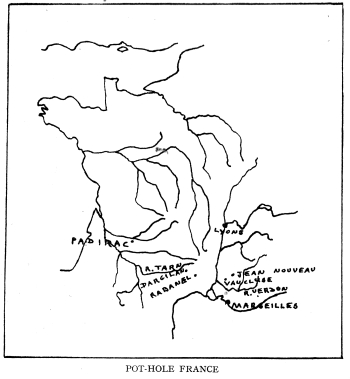

Martel’s first pot-hole campaign met with astonishing success, though he had only 40 feet of ladder. First he traversed the labyrinthine watercourse of Bramabiau from swallet to outlet, descent 300 ft., air-line 600 yards, a lucky feat the like of which I doubt if he was able to parallel, though he proved such traverses possible more than once. Then by rope-hauling he did a four pitch pot, and went down the great chasm of Dargilan to reach the dry bed of an ancient river, the prettiest cave in France in its day, though its forest of stalactites may now yield pride of place to those of the Aven Armand (1897) and the Aven d’Orgnac (1935).

Next year, 1889, he had an amazing four weeks in the Causses, with his cousin, Gabriel Gaupillat, and two local men, Foulquier and the famous Armand. The party had 100 feet of ladder, relied principally on rope-hauling, and had assistance of course.

I trace Aven de Boussoles, 3 pitches, 180 ft. ; Aven de Combelongue, 280 ft. top pitch 65 ft. ladder, several narrow pitches climbed with rope. Then Aven de I’Egue, first pitch 200 ft. laddered half-way and then descended on the body-line. Climb to 295 feet depth. Foulquier, last up, tied himself on with a slip knot and was nearly ” done in.” The party spent the night practising knots !

This narrow escape made Martel adopt a curious method which I doubt if anyone else has used regularly. The life line was never after tied round the body, but round a notch in a two foot stick. On the stick sat the man, kept safe only by a double cord loop over one shoulder outside the rope, and under the other armpit. One cannot conceive how in moving about on a ledge with a slack rope, the whole affair did not sometimes come loose.

Possibly it did, and the fact has been kept quiet. Attentive reading of Martel’s and Joly’s writings shows how certainly everything that can go wrong in a pot-hole will do so in France as in England. That is why so many of us are averse to practices and gadgets which work admirably in daylight. For example why not have a belt with a hook on it to put round a rung ? Joly, the leading spirit of pot-holing in France between wars, has one, and when surprised by a flood in Paradis on his way up 150 ft. of ladder, the hook caught the ladder, held him up and by main force he had to be hauled up, ladders and all (probably his light wire ladders).

Next, Aven de Guisotte, total 236. ft., first pitch 220 ft. ! After 100 ft. Armand could not be heard. He therefore sat tight at the bottom until Martel arrived on another rope. Another lesson. Never again did they go down over a huge distance without a telephone.

Aven de la Bresse. Several pitches, total 394 ft. There was a whole series of mischances and they got really angry with one another.—Aven de Tabourel, 4 pitches, 436 ft. Ladders lowered and refixed three times.—Aven de Hures, 3 pitches, to water at 381 ft. When dry, if a certain tree trunk can be passed, this pot has been done to 672 ft.

Abime de Rabanel was the most celebrated and monstrous of these yawning gulfs. Martel was below five hours the first day. He was lowered 425 ft. to the top of a talus slope, 115 ft. high, down which he went into a great hall with superb stalactites. The next three days were taken up with Armand’s construction of a great tripod and windlass gear for two ropes. With the aid of Gaupillat and Foulquier Martel then took the telephone on to an 80 ft. pot, and descended to a depth estimated at 695 ft. This was the first of the really deep French pots to be done, It is now put at 195 m. (640 ft.) but several of those which nominally exceed it will probably have some metres knocked off.

Grotte de Sargent, 460 m. long. After wading to the waist for 60 m. Martel swam the end pool naked. Another ” never again ” !

Abime du Mas Raynal. A noted chasm, first pitch 213 ft., total 345. Here they found a great pool, 60 yds. by 15 yds., running off in cascades, and explored 350 yds. of watercourse. On the surface gathered all the countryside and a bal champetre went on. In the rock wastes of the causses, denuded recklessly of their forests, the pots are almost all dry, and this was the first time Martel had reached running water.

The last and greatest discovery came next day but one— Padirac ! The great chasm of 175 ft. had been done once to recover a corpse, but the four went further and came upon an undei-ground river. The second day Martel and Gaupillat in a collapsible boat made a voyage lasting 6½ hours. For long distances the stream goes down in basins great and small, gours, and each slippery rim means a landing.

Les Cevennes was published in 1890, and from that date the Causses began to develop as a tourist district. It is no wonder that Martel stood in high regard locally, and that at the junction of the Tarn and Jonte there is since 1927 a monument to him and his comrade Armand.

The 1890 campaign was a fortnight in September and began by finishing off Padirac. The four, with De Launay, were underground 23 hours, and reached a point estimated at 2½ to 3 km., actually 2 kilometres. Later some progress was made in 1900. (In 1938 Joly with all the advantage of 1,000 yards sight-seeing development made progress with great difficulty and after 11½ hours and a further voyage of 350 yds. turned back where he saw the river still flowing quietly ahead.)

Igue de St. Martin, nearly 300 ft., first pitch 213. A murderer had thrown himself down a branch of this shaft the previous winter, survived, was rescued and sent to prison.— Igue de Bar, total 213 ft.—Grande Igue de Cloupman, nearly 300 ft. in one pitch.—Igue de Roche Percee, 328 ft. in one pitch. Other smaller pots and caverns. Martel also visited and studied the Grottos of Han and Rochefort in Belgium.

1891. He was equipped with 200 ft. of ladders and used them now as the regular thing. Igue de Gramouillat, immense shake-hole, 100 ft. deep, 165 ft. pot at the bottom. Abime de la Crousate, passage to three pitches, 280 ft. total. Contains remains of an ancient gantry and bridge !

At the bottom of the Gouffre de la Berrie, 90 ft., a dead calf lay in water. The party drank from a clear spring lower down and were all poisoned, Martel worst of all, so much that he did not get over it for six months.

In September he went out to Greece and with Siderides visited basins of internal drainage in Peloponnesus. One of the swallets was forced 50 yards in spite of the horrible stink of decaying rubbish. Martel was seized with fever that night and could do nothing more. An unlucky season.

In 1892 Martel had 460 ft. of ladder in use, having become a complete convert. Creux Percee (Dijon), open pot, glaciere, 180 ft. total. Creux de Souci (Puy de Dome), 108 ft., in lava. Carbon dioxide stopped each man a few feet from the bottom of the ladder.

Igue des Combettes, first pitch, 180 ft., total about 300. A roaring river was found and followed 200 yards down ten cascades. Igue de Viazac, no stream, first pitch 213 ft., total 508.

Aven de Vigne Close, five pitches, first two 180 and 150 ft. A classic example of the horrors of the relay system, six men being left at the top of the fifth vertical and three at points above. Fifty feet of ladder were taken off the bottom of the second pitch ladders, and let down over a pulley. Sixteen hours work the second day.

Grotte de St. Marcel d’Ardeche, surveyed and knocked down from six to two kilometres.

Far back on the uplands east of the famous rising Vaucluse, three smaller pots were done, and the colossal Jean Noiweau, a dead drop of 535 ft. Ladders were put over, but Armand and Martel were lowered on two ropes, practically together and very slowly by thirteen assistants. A small pit at the side which Martel refused has been done since, making 610 ft. total depth.

Among other caverns he revisited Bramabiau, three more traverses having followed his, and added 400 yards to the labyrinth ; while in Boundulaou, he used a boat, reaching the channel of the permanent rising.

1893 was Gaupillat’s last campaign ; so far he had been even the more active. The Grotte de Miremont was surveyed and found to add up to three miles. A short campaign only did the Viazac (508) again and the Planagreze (256).

The September visit to the Adelsberg (Postumia) cavern in Carniola beyond Trieste was a brilliant success. On the 15th the Antrona Club’s voyage down the underground river, Tartarus to Ottok Cave, was repeated. On the 16th Martel with six others managed to do 800 yards down the Piuka from Ottok to a fork near Magdalenen Schacht. Many barrages were passed to a siphon, avoided by carrying the Osgood boat through tunnels in a boulder jam 200 yards ; a hundred yards more voyage by 6 p.m. and turn back.

The Piuka next day was in flood at the Kleinhausel exit, while the branch from Zirknitz was so dry it could be followed, but so fearfully rough was the torrent bed only 500 yards could be covered in two hours.

Another day the Magdalenen Schacht was laddered, 70 ft. and 120 ft., and in spite of a rising flood on the Piuka, a short voyage upstream found the fork reached before. Martel had added 1,500 yards of river, doubling its known extent. On the 23rd he was taken by Marinitsch and others 1,150 yards down the gigantic cavern gorge of the Recca to cascade 20, beyond which more progress had been first made only on the 6th September.

His expenses so far had been borne officially but he went on in October at his own expense to Bosnia and Montenegro, showing the existence of no end of caves, but apart from notable progress alone in the Grotte de la Rjeka (Cettinje area) he could do nothing.

So far I have found no note of caves done in 1894, but Martel probably climbed in the Alps as in 1895 he published with Lorria Massif de la Bernina. This same year 1895 he attended a Geographical Congress in London to read a paper, and took the opportunity to make his famous British campaign, visiting first Peak Cavern and Speedwell, then going over to see the three subterranean rivers of Ireland mentioned in Kinahan’s book, the Cladagh (Ulster), Cong, and Fergus (Clare). Here he made the first exploration of the Marble Arch, the descent of Noon’s Hole two pitches, and finished by surveying Mitchelstown New Cave. Then on 1st August he made the amazing descent of Gaping Gill (see A.J., Vol. XVIII.), 270 ft. rope-ladder below 60 ft. of double rope, with a knot in the life-line, and his only experienced support his wife at the telephone, yet read his paper in London next day.

In 1894 Martel published that great work, literally so in weight and format, Les Abimes, and in 1897 Irlande and Les Cavernes Anglaises (in 1914 one of the only two books on Ireland in the Alpine Club library). There is no foundation for the legend that he did Sell Gill Hole, and no trace in his books that he attacked more than one Yorkshire pot-hole.

These varied experiences led Martel to a correct appreciation of the problems of the limestone. The rock covers or closely underlies two-thirds of France, thus the striking thing to remember is that the French shafts are commonly far distant from and at a great height above the risings, which deliver the water of great areas of thick limestone. In the pot-holer’s sense they are dry or dead. The usual view of the day was that the fissured rocks contained nappes or sheets of water waiting to be tapped, that the Causses were carried on great rock pillars over great vaulted reservoirs.

Down the black precipices of the pot-holes. Martel reached in rare instances, definite streams at all sorts of levels, and found no water-table. In the ” mere caverns ” he followed water-courses, active or abandoned. First then the pots were no marks of underground rivers, second the stream courses were as definite as in the open air, third there was no filtering of water in its passage. Once poisoned the water burst forth non potable. The theories formed were confirmed as correct when he came to England and found our pot-holes very much alive, that is in course of erosion and corrosion by streams and seepage. It is interesting to note here that the French limestones are Jurassic, Oolitic and Liassic, ours are Carboniferous.

Martel’s merciless cudgelling of out-worn theories must have offended many people. How much it was needed is shown by the recent very amusing outburst in England of the story of great reservoirs in the limestone available for water supply. Still it is astonishing to find a responsible geologist as late as the dispute over the Perte du Rhone (1911) saying of him, ” If men accustomed to stroll about in the yawning faults of some regions wish to see like phenomena everywhere that limestone exists, it is the finest demonstration of the pre conceived character of their ideas.” Yet at this late date Martel was an acknowledged authority.

Nevertheless a ” geomorphologist ” a few years before had also dismissed his work as ” theories maintained by dilettantes of the exploration of caves.” It is a matter of frequent note that any number of armchair pundits claim a voice of authority when it comes to things underground in the limestone. Not many years ago the Editor of the Naturalist told us that the Y.R.C. explorations had retarded progress (Naturalist, 1925, p. 223 and Y.R.C.J., V., p. 236). Martel frequently complains that people underestimate the efforts exacted by work of any difficulty underground, and notes that he and his have been called, sporting hunters of stalactites (a libellous accusation !), excursionists, autodidactes, etc.

In 1896 came a short visit to the Pyrenees, but there was more important work done in the vast rock deserts of the Vercors, S.W. of Grenoble, and in the Devoluy to the S. In the great cave of Brudoux, he got forward by boat and ladder 400 metres upstream, and in 1899 to 750 m.

In 1897 Aven Armand was discovered, a magnificent great hall, 150 m. X 50 m. X 50m., reached down a 264 foot pitch, with a floor sloping at 400 and carrying 500 leafy columns. On the Devoluy he descended Chourum Clot, and in 1899 discovered the colossal Chourum Martin which he descended 230 ft. after a week’s work owing to the appalling stone avalanches and the clearing needed. Chourum Martin made a tremendous impression on his mind, frequently alluded to, and he believed its depth might be over 1,000 ft. Joly finally got down in 1929 and found it 190 m. or 623 ft. (accurate). An adjacent pot-hole higher up has recently been found to open into the same final chamber.

1899 also saw an expedition at Ministry expense to the pot holes miles and miles away behind the famous rising of Vaucluse, yet connected with it. In Grand Gerin, 394 ft., a rope jammed and broke, 100 ft. of ladder being lost, while another 60 ft. were lost in Jean Laurent (426).

A great epidemic broke out among the garrison of Lure in 1898, due to drinking water polluted by dead beasts thrown into pot-holes many miles back. The greater depth of the French pot-holes makes decomposition slower and more poisonous than in England, the conditions met with being often abominable. A tremendous fuss was made in the Chambers, and Les Abimes had been read. Martel was quoted as an authority by Ministers in debate and his work alluded to as ” revelations.” By this time his brilliant services to public health had given him an outstanding position.

A Ministerial circular of 1900 required every water scheme to be submitted to a commission of a chemist, a geologist, and a bacteriologist. The assurance of legislation was fulfilled by the law of 1902, prescribing perimeters of protection round water intakes and forbidding the throwing of dead animals into swallets and chasms. The latter has not been enforced since 1918 and the country people to-day consistently ignore it.

In the next five years Martel paid two visits to the Pyrenees making a plan of Betharram, 3½ km., and an official tour for the Russian Government on the S. side of the Caucasus to compare the Black Sea coast with the Riviera led to the appearance in 1909 of Cote d’Azur Russe.

From 1904 to 1915 he was joint Editor of La Nature, and from 1905 to 1914 he with his brother-in-law, the geologist De Launay, was regularly employed on official missions by the Ministry of Agriculture and as a member of its Committee of Scientific Studies, chiefly on water supply and reservoirs for industrial purposes. Owing to the vast extent and thickness of the limestone, the problems of source and effect are much vaster and more puzzling than in Britain.

One traces 1905 as again a campaign in the grand manner, fifteen descents above Vaucluse, four above 80 m. (260 ft.), and the sensational descent of the Great Canyon of the Verdon, ” the most American of the canyons of France.” Next year he did it upstream and also two much shorter magnificent clues. In November he came to Leeds and lectured to the Y.R.C., as printed in Vol. II., being then made Honorary Member.

A campaign in the Pyrenees in 1907 at his own expense was followed by extensive official investigations during the next two summers, four months’ work resulting in 150 plans. Gouffre de Barranc (260 ft.) seems the deepest pot done, and the formidable underground river Bouiche was forced upstream beyond 250 metres to nearly 1,600 by using boats until they were too damaged to continue. A determined attempt was made by Fournier to descend the canyon of Olhadibie, and another upwards in 1909, led by Martel, without being able to pass two terrific falls.

At the end of this came the decoration, Officer of the Legion d’Honneur.

In the Jura, 1910, was made with Fournier the classic experiment with fluorescein, when 2 cwt. was put into a leak in the bank of the Doubs to come out days later at the rising, La Luire, many miles away. In Padirac Martel pushed on in 27 hours to 2,090 metres. Les Cavernes de Belgique was published the same year.

Next came official enquiry into questions of water supply to Toulon, and the first careful study and plan of the Rhone below Bellegarde, relative to wild cat schemes of flooding it by a huge dam. It will be news to most of us that the Rhone here narrows to 5½ feet, emphasizing the craze in France for industrial barrages holding up quite trifling quantities of water due to the difficulty of finding the type of site we in England think fit for a reservoir.

In 1912 Martel went to the U.S.A. and visited the Colorado Canyon and the Mammoth Cave where he made very unpopular reduced estimates of its great length.

Armand, his great supporter died in 1921, the year of publication of the great volume Nouveau Traite des Eaux Souterraines. This was followed by Causses el Gorges de Tarn (1926) and by La France Ignoree (1928, 1930), a work which has drawn attention to innumerable remarkable things and to which many places in France must be deeply indebted for solid business reasons. To the great services Martel had rendered to the poor communities of the Causses and Tarn by the developments which followed his discoveries and writings a remarkable testimony is given by the unveiling in his lifetime of a statue, with plaque of Armand below, at the junction of the Tarn and Jonte. This day in 1927 he was promoted Commander of the Legion of Honour, but unhappily, a few days later Gabriel Gaupillat died, his cousin, and comrade of six glorious years. 1928-31, Martel was President of the Societe de Geographie.

Of predecessors in the 18th century he had three, one of them Lloyd at Eldon Hole ; 19th century pot-holing begins with the remarkable excavations of Lindner in the Abisso de Trebiciano, which took him down to 1,056 ft. to water now judged to be the Recca. Then came the interlude of the work of Birkbeck in Craven (1848) and of Schmidl in the Adelsberg cavern in Istria. The resumption of work in the latter area was in hand when Martel gave it a great impulse by his visit in 1893, and the Y.R.C. had just begun work in England when Martel came over in 1895 to descend Gaping Gill.

Martel opened a new chapter in geology by laying down the laws of underground flow in fissured rocks, destroying the idea of water levels in such rocks and substituting the idea of independent water-courses as on the surface. Limestone is of course the principal such rock but he also proved chalk to be of the same character, except where it is in a fragmentary state. He never failed to castigate the theory that great reservoirs exist in solid rock. To-day engineers have learned at last that no limestone can be trusted not to be fissured. That the formation of stalactites ranges from very slow to very rapid was another of his unpopular views.

He was of course a firm believer in the relatively protective character of snow and glacier, compared with the powerful excavating tools of frost erosion and glacier torrent, in other words be insisted that glacial action is a highly complex and not a simple affair.

In France with its immense thickness of limestones and its far-stretching limestone plateaux the pot-holes are for the most part dry, and my impression is that bedding-planes are an unimportant feature in comparison with the joints. Remember that Martel writes of bedding-planes as joints and of our joints as diaclases.

A most refreshing thing about his writings is the trenchant attacks on fantastic technical terms, bad Latin and worse Greek, useless neologisms. He lays it down that new words should be invented only for new phenomena. With the hokum and obscurity of third rate science he had no patience.. Modern geography suffers severely at his hands. With its emphasis on the U & V valley idea, one glacial erosion, the other water erosion, he did not agree, first because he put down the U & V shapes to the rock, and second because there is every gradation between.

Full of years and honour Martel died in June, 1938. Great as were his services to tourism let us not for a moment allow the gratitude of the natives of the Causses, Verdon or Pyrenees to distract our view of him as a great geographer and explorer. Greatest of all in the underground world, to all pot-holers he was “The Master.”