Round Sutherland

By The Editor.

The Sutherland clearances, fishing, bad roads, and strange isolated mountains, the worst climate in Britain at Cape Wrath, and a population of the scantiest, about sum up all I knew of the far north-west of this island. The late J. H. Buckley once drove up to John o’ Groats and elsewhere, and was deeply impressed by the long, lonely, and desolate stretches of road. It was always my intention to get to the neighbourhood of Cape Wrath when the opportunity came to go in one of the drier months. As for the roads, reassuring information came from I.C.I, men who had been, that a man who habitually took his car off the tarmac had nothing to worry about.

The opportunity came in 1934, and I left Leeds with my cousin on 16th June after three weeks of glorious weather following a Whitsuntide of evil memory and general flooding. To start in the cream of the year was to give Sutherland every chance. After a week-end at Biggar, we went north on the 18th, via Stirling, but taking the road to Crieff where one abruptly enters the Highlands, winding through the Sma’ Glen (Glen Almond), across to Amulree, and down to Dunkeld on the usual route to Inverness. I thought I had seen plenty of broom in my life, but in Scotland the sheets of blossom were stupendous, and in the Highlands it was everywhere, far exceeding any show of gorse. We had a glorious drive, but at Dalwhinnie a breeze got up and the sky was overcast. From Speyside over to Inverness there is a most extraordinary alternation of dense and splendid woodland with wide bare moorland. I regret that I have forgotten the names of the lairds whose determined policy of planting effected this enormous change for the better. Ten miles beyond Inverness, in a shower of rain, we pulled up for the night at Beauly, over 200 miles of a run.

Beauly is a pleasant place, in the tourist’s eyes much more suitable as a stopping place than either Inverness or Dingwall further on. One is here in that narrow strip of lowland coast, in which, although the Lowlands (with a capital) are generally reckoned to end at Nairn, the inhabitants of the towns consider or considered themselves as anything but Highlanders. If you don’t believe it, read Hugh Miller of Cromarty, My Schools and Schoolmasters, Chap. XXII., and many earlier passages.

Beyond Dingwall we left the characteristically lowland highroad for a characteristically Highland road to cut across the hills from the Cromarty to the Dornoch Firth at Bonar Bridge. The first few hundred yards raised some misgivings, but the road soon settled down into a recently made tarmac surface, and the John o’Groat’s buses and other traffic which passed during our first halt soon reassured us. Beyond Bonar Bridge we were in the Sutherland type of country, and on the kind of road we had heard about, too narrow as a rule for cars to pass, but provided with occasional passing places. We came across some unfortunate ladies who had been ditched by a lorry. The only help we could give was to tell them that plenty of people had been ditched in the Highlands but did not talk about it, and that the rescue van would have them out in five minutes.

Beyond Lairg we entered on 20 miles of appalling desolation to a hamlet called Altnaharra, on the Tongue road. Vast gentle flat slopes with nothing on them and the poorest of flora, stretched away far to the west where loomed bold hills. Even the becks failed to bite into the surface, and it was a relief to strike the great torrent pouring down to Altnaharra and Loch Naver. The day had turned out showery and overcast and anything but warm. The idea of bagging a Munro, Ben Klibreck, had to be given up ; we only saw slopes running up to a cloud. The road was-nine feet wide, ran in long straights with mostly good surface, and had passing places with signs every hundred yards. Seemingly all the roads across Ross and Sutherland from one coast to the other had recently been overhauled.

Nearer Tongue, Ben Loyal was a fine sight in its towering isolation above the moor and Loch Loyal, and the day improved. The roadside was more attractive by the lake with a few birches and wild flowers. I even found one of the more uncommon kinds which I was hoping to see.

A climb over desolation again, and we ran steeply down into Tongue, which stands on the east side of one of the great north coast inlets with a magnificent view of Ben Loyal (Scottish rendering of the Gaelic Laoghal). Between us and Cape Wrath were three of these great sea-lochs, Kyle of Tongue, Loch Eriboll, Kyle of Durness. Down by the sea is a great house with extensive woodlands. Those who think trees won’t grow in Sutherland because the climate is so severe should see these—there is everything usual, sycamores, limes, sweet chestnuts, etc., growing freely.

Most people would not hesitate over pronouncing ” tongue,” but in a region of which the place-names are Gaelic and Norwegian, one does not expect the liberties of English spelling, and the name was probably of two syllables originally. It is a direct Norwegian name, for in the story of Burnt Njal, the most famous Icelandic saga, Flosi and the Burners rode west over Thurso-water, to another Tongue, the house of Asgrim Ellidagrim’s son, and had the cheek to call for breakfast. Thereafter, provoked beyond the law of hospitality, Asgrim tried to pole-axe Flosi.

We had anticipated that we were early enough in the year to have no difficulty about accommodation, but it was very soon brought home to us that the only large business in Sutherland is looking after fishermen, not casual tourists or ordinary visitors. The hotel was full and booked up for months ahead, but has some little rooms in an annexe for passagiers. The class of client means, of course, that they do you very well.

The 20th was bright and clear. We went south to the head of the Kyle on a fair but narrow road with few passing places. I left the car at eleven and crossed wide dry levels in the direction of the col N.E. of the smallest and most westerly peak of Ben Loyal. There was no doubt that Sutherland had been through the same drought as the rest of Britain. In an ordinary season my route would have crossed the most terrible bogs. The slopes of Ben Loyal shoot up from the bogs with astonishing suddenness, but carrying a sprinkling of trees, and I was soon looking across an amazing scene, sprinkled with tarns, to Ben Hope, the most northerly Munro. From the col I was cut off by a line of stiff crags, but there was no difficulty on the slope of the peak itself, and I was up at 12.45. Cloudberries were abundant and I was lucky enough to see some Dwarf Cornel, a delightful little flower of which the North Riding once had some patches, but I fear has lost them nowadays.

My little peak, unnamed, 1,750 ft., conspicuous on yesterday’s drive for its isolation from the main mass, gave a most striking view of the two nearer peaks of Ben Loyal. It looked, in fact, as if I might be a long time in finding a way up. The face of the two of them was simply one line of superb crags towering for the most part above a long and narrow tarn. However, above the col at its head was something of a break in the line, and I was very lucky in spotting a deer-track which went up an exciting scramble of steep grass and slabs. It was a glorious day of sun and cool wind with a grand view out to the sea. I was very pleased with having come what is probably the finest route over Ben Loyal, one not suggested in the S.M.C. Guide.

I passed over the second of the two peaks at 1.45, crossed to the main ridge, and halted out of the wind below An Caisteal (2,504 ft.) at 2.20. On the way I had seen Sea Thrift and Moss Campion, and sent a flock of hares scampering off one summit. An Caisteal is a fine granite tor with at least one climb on its S. side and a huge sloping slab on the N. The North Summit, another granite tor, was twenty minutes away, and from it I reached the bogs in 35 minutes, during the last part of which I was glad the wind was cool. Another twenty-five minutes by almost as dry a route as on the way out took me to the car, 53/4 hours.

Pleasant as was this day it turned quite cold after our picnic tea and we were not surprised to find Thursday very misty and gloomy. From Tongue we drove round the head of the Kyle, and leaving some natural woodland behind went five miles down till opposite Tongue, then over six miles of upland, a dreadful wilderness, no rock, no becks, and no sign of Ben Hope which I had come to climb. We had begun on the Sutherland coast road, a great joke among roads, a joke 100 miles long. Once it had been two cart-ruts, now with the help of the excellent Archaean rock, its rawness smoothed by mixture with earth, it is the highroad from Tongue to Durness, to Scourie, to Loch Inver, and south to the Achiltibuie road. It is seven feet wide, you daren’t get off it, and in most places as it is either sunken or raised, you can’t; passing places are few and far between. After your first meeting with another car, you learn to call out mechanically, ” passing place,” to impress on your mind what the situation is when you spot something ahead, whether to push on in hope or go back at once. The Ministry of Transport has just made a heavy grant to Sutherland, so if you wish to test your driving and the comfort of your car, get there soon.

A steep descent to Loch Hope, a glen parallel to Loch Emboli, running into it near its mouth, and we turned south along the lake on a ” road ” which goes through to the Altnaharra of our route north. It was a pleasant drive ; half way along Loch Hope one enters thick natural woods of birch and willow, no firs, and the scenery is that of the Highlands we were used to. The road is 6 to feet wide, and after a time we began to realise we might be in trouble ; there were no passing places. There was nothing for it but to push on prayerfully, and after six miles, at the very head of the lake, we found a place where fishers had already parked a car, with room for another.

Ben Hope was a marvellous Alpine sight, great buttresses covered in the lower parts with trees towering into the face and losing themselves in the cloud. In fine weather I expect it looks much less impressive, but I notice that J. H. B. Bell found quite a sporting ascent from this side. To-day there was no point in trying it.

The idea of going over from here to Loch Erriboll by a road shown on the map and seen on the hillside fell flat, there was certainly no bridge, and there did not appear even to be a made road to the ford. The flora was extraordinarily poor, so after lunch we bolted back down Loch Hope as fast as I dared drive, then over the hill to Loch Erriboll. Bare and desolate as are the hillsides and shores, and gloomy as was the day, it was a grand and striking scene. The road was very bad at the head of the loch, mere shingle, and later on we met a car and went back a bit to the only passing place we had seen for miles. Next we passed a long stretch of crofter dwellings. The road here was solid enough but rougher than anywhere else on the whole 100 miles.

Several warships were lying in Erriboll and on this western side there were numerous parties ashore, playing football, etc. We met detachments marching, who appeared to be soldiers, not marines. Later we learnt that the Admiralty own much of the uninhabited land round Cape Wrath, and that the fleet regularly conducts firing and landing exercises there.

A really grand piece of rocky coast, by the open sea for the first time, came next, one little bay after the other. All at once we had a narrow blue inlet running close in on the right, and a beck flowing under the road from the left. There was no bridge—here was a pot-hole ! Some people say that I went to Sutherland because of the Cave of Smoo’, and I will confess that amongst the luggage were the wire ladder and another. The afternoon was brighter, but on getting out of the car the bitter wind by the sea gave one quite a shock. A run round showed that the pot was probably more than one ladder, and one was glad to take shelter in the cove. We were a mile or so from Durness, and several boats were drawn up here. At the head of the cove is an enormously wide arch ; the stream comes from a side cavern within, cut off by a barrier and containing a huge deep pool curving into the darkness to the left. By climbing on to the barrier and a little out on the right wall, the waterfall can just be seen. Somewhere I have come across a writer who had had a boat lifted over the barrier and who got a better view.

There is a temperance hotel in Durness, but the fishing hotel, where I had fortunately ordered rooms, is at Keoldale on the Kyle of Durness, two miles on, forty from Tongue. The journey is possible on foot, as two ferries cut off many miles. A walk in the evening showed that the flora by the coast was quite interesting and the weather showed signs of being warmer. After two poor days out of three we were wondering if Sutherland weather was always bad, but the Times indicated that the South was having a poor time and next morning we were positively cheered to open a copy, 24 hours late, which had a column headed “Ascot Ruined.”

Friday was spent in a walk right along the coast from Keoldale to Faraidh Head (Far Out Head) and round to Durness, and as the day wore on the weather became warmer and more sunny. As far as the narrow isthmus there was sand, and low cliffs, after that the rocks rose to a striking height. It was the first time I had seen a really rocky coast, other than chalk, and the views were most impressive, particularly along to Cape Wrath. Dry as Octopetala is common high up in the Alps, it is rare even in the limestone of Northern England, but here it was fifty-fifty with the grass on the sea-cliff, flowers mostly over, but with abundant very large blooms on some inland banks. Sea Thrift was abundant, and Silene maritima, the white Campion of the Wasdale crags in July. There were many patches of Yellow Iris.

To reach Cape Wrath it is necessary to use the Keoldale ferry and then to tramp eleven miles along a dreary road and eleven back. The usual method is to make up a party and do the journey in a wonderful old motor which the hotel people have taken across in pieces and reconstructed on the west side. There is an area S. of Cape Wrath, about 10 miles square, where there is not a human being.

The 23rd was a blazing hot day. Eight miles up Strath Diomaid and over a pass we suddenly came from the drift and peat-covered region of the north coast into an entirely different type of country. In a few miles we passed the head of a sea loch in delightful scenery—more bracken, more birches, more rock. The bones of the land, the Archaean gneiss, stuck through in hills and knolls, the road swung round a hillock, past a lochan, over a burn, up and round another hillock, along more burns and by more lochans, past Laxford Bridge where for the first time we might have turned back across the county to Lairg, and so to Scourie. Then on, another fifteen miles or so of twisting road through a lonely and delightful land, where the only sign of life was some fisherman’s car parked handy to some lochan, duly assigned him on the list daily exhibited in the Scourie hotel.

We lunched near Kylestrome in the superb surroundings of the Kylesku Ferry, half way up a huge sea loch, by the amazing strait above which it splits into two mighty arms. Opposite towered Quinag, great peaks behind a great corrie flanked by impressive crags. If Quinag is not the most famous peak in Scotland as a local guide-book claims, it is certainly one of those worth travelling far to see, and to climb. Kylesku Ferry is easy, the ferry boat runs up end on, the ramps are not too steep and are free from seaweed, but the bump on to the boat is still sufficient to damage the tail ends of the more absurdly built modern cars.

Beyond Unapool the car climbed steadily for some miles on to a moor at 849, E. of Quinag. At the bottom was a gate opening on to a vile road N. of Quinag. Namesakes of mine, a father and a son, in an excellent £5 Humber, had passed us while halted at Kylestrome, and were so attracted by Quinag that they took this road and after ten miles of adventure, awful surface and hills almost too much for the car, emerged on to a comparatively Christian road at Drumbeg. As for our road it got looser and looser, and sometimes very narrow, but was always passable. Then we saw Suilven and Canisp in front, and Ben More Assynt to the left, and so down to Loch Assynt, a great sheet of water, seven miles long. Inchnadamph is at its head on the road to Bonar Bridge on the E. coast.

What a difference, a nine foot road with passing places, a racing track ! I fairly trod on the gas till we had to stop to look at the view near the end of the lake. Then winding down a delightful glen, to the woods and open sea of Loch Inver. The hotel is small, and the word was—” booked till the end of September, Inchnadamph probably the same.” It looked like Bonar Bridge that night, but the landlord relented and mentioned that there was a boarding-house. Seaview House, Miss Forbes, is an excellent place, with a large sitting room upstairs and there we stayed. Later we saw our friends coming in after their tremendous round from Kylesku, and brought them in. The summer days are long in these latitudes ; we saw the sun shining at ten p.m., and went out to post letters at eleven in broad daylight.

One hot day had passed, but it was nothing to the next, which scorched the skin of my face as it has only been scorched in the Alps. I went up Suilven with George Roberts, jr., his first mountain. It involved a long walk up Glen Canisp, so to save some grind we took his car up to Glencanisp Lodge.

This is a private road, but the inhabitants of the lodge are not so fierce as is usual. Meeting us on the road two of them backed their car ever so far and then gave us advice about not going further. Nevertheless a man with a car with a low bonnet who can see where he is going is not to be deterred. The track beyond had once had a foundation wide enough for a car, and for half a mile we proceeded crushing down bracken, gorse and broom, till stopped by a narrow gap in in a wall. Here we left the car, for good I thought, and followed a very bad path for miles. Then we struck up heather slopes past some tarns, and by very steep grass slopes went up the N. side of Suilven, just beyond the formidable looking Grey Castles, the sea end. The wonderful view was rather spoilt by haze, as the day passed.

From the summit, back along the ridge, up the middle peak, and then along the ridge, to be startled by a sudden gap and the formidable appearance of the precipitous face of the lowest peak. Keeping to the left of the crag it gives a short and pleasant climb. We kept on to the bitter end of the ridge, rounded the head of Loch na Gainimh, bathed, and found Glen Canisp decidedly long in the blazing sun. At 7.15 we contemplated the car, at 7.30 it was apparently fixed for ever across the road with a pair of wheels in each of depressions which had once served for ditches. On such expeditions carry a spade, the handle of the jack is quite inadequate for digging turf. The brain wave which sent us away at eight was to use two long and heavy stones which could be rolled. Driving off these the car heaved forward an inch or so up the bank, one stone was rolled forward and jammed in place, the clutch released, then the same process for the other wheel, and bit by bit the back wheels mounted to the top of the stones. The spray of rubber when driving off edges was wonderful, but the tyres seemed none the worse. A little filling in and the back wheels were on the solid foundation, and we proceeded on a triumphant career through the gorse bushes, very late for dinner.

On the 25th my car carried the party to the shade of the trees by Loch Assynt Lodge, and by the wrong path first, through bog myrtle and deep heather to the right one, the same two fared forth to bag all the peaks of Quinag. Five

peaks ran in a line on our right and the highest was on a great spur behind the middle one. The path was a tremendous help, the walk to the pass only a mile, and the variety of scene much greater than on the Suilven day. From the pass we traversed the slopes of the middle peak, point 2,448, gradually ascending till we were right under the dip in the ridge north of it, then straight up a very steep slope.

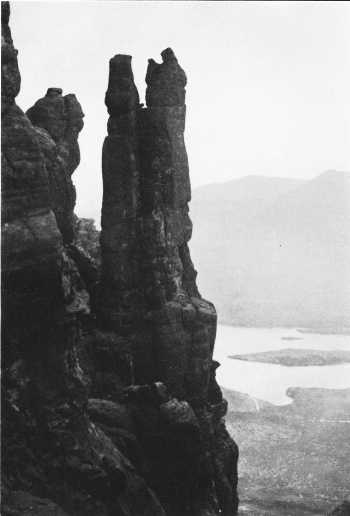

The hillocks and rock basins of the west coast are Archaean rocks, the strange isolated mountains are Torridonian, the next younger rock, and some of them, like Ben More and part of Quinag have caps of gleaming white quartzite. Torridonian is a sandstone, which goes several better than millstone grit in its absence of holds and in the rounded edges of its strata. We gained the ridge through a break in a line of formidable crags stretching far to the north, our left, passing through rocks of the ” hot cross bun ” type, i.e., the ends of the aretes went up in towers which looked like great piles of stone buns. Where the Torridonian is not in impossible faces, it gives many an amusing climb, where a new technique, the arm-hold round a segment of ” hotcross bun,” has to be learnt.

It was a glorious day; we saw islands, lochs, a land covered with hundreds of tarns, and a perfect mountain view. The heat was delightful, but up there on Quinag the sun was at times almost intolerable. I have read that in the tropics the sun is an enemy, and I had the feeling then that the sun was almost hitting me. Never in the Alps have I had such a terrible scorching as on the peaks of Quinag.

We had gained the ridge in an hour and three-quarters, and after a long rest went on over a 2,000 foot point a mile to Sail Ghorm, 2,551, 2.40 p.m. There were grand views down the line of crags, and we saw many a narrow ridge and tower of the quaint Torridonian kind. There must be many climbs on Quinag, waiting. From Sail Ghorm we came back and climbed slowly to our third peak, 2,448, then without much descent went east to the highest summit, 2,653, a quartzite-capped peak (4 p.m.). Returning most of the distance, we had to go down quite a long way and then climb very steeply up to 2,306. The sun was at its worst, and Spidean Coinich, 2,508, looked a terribly long way above. One more effort and all was over, bar shouting. Quinag is a grand mountain ! An easy line down was spotted, the pass below gained in 35 minutes, and the path to the road at a cowhouse, not at the Lodge, travelled in seventeen. Here by the trees and the lake the midges fell upon us.

On Tuesday our friends went on, but my cousin and I remained at Lochinver to loaf by the sea, and let my face heal. Iris was everywhere and in the gardens a profusion of the old Scotch yellow rose. The summer flora seemed quite early with a curious lingering of spring flowers. At Lochinver were the only firs we saw on the coast run.

North of Inverness one is beyond the influence of the Prince Charlie legend with its curious suggestions of Scotland as a Roman Catholic country, ruled by Englishmen, and held by English troops. Sutherland went Protestant early and began to settle down 100 years before the rest of the Highlands. Clan Mackay held the north of the county, the Sutherlands the south. The Mackay, the first Lord Reay, fought through the Thirty Years’ War, and is stated to have recruited 12,000 Scots. Another Mackay led the Scottish army at Killie-crankie. The fighting forces from this now desolate district in the old days are surprising, the Sutherlands mustering 2,000 claymores in 1745. A month before Culloden a French force compelled to land at Tongue was captured by the Mackays, Munros, and M’Leods ; the day before Culloden the Sutherlands and Mackays with hardly any loss destroyed another force of 250 Jacobites at Dunrobin. Prince Charlie would have had a poor chance had he landed among these stout Presbyterians. The names of the clans which formed the seventeen independent companies holding the Highlands after the departure of the regulars, Mackays, Macleods, Munroes, Macdonalds of Sleat, Rosses, Gunns, etc., show that beyond Inverness you have left behind the clans of Charlie’s dramatic and gallant adventure.

The 27th became a morning of heavy showers during which I wrestled continuously with the problem of removing part of the engine tray to locate and recover a nut dropped in from the oil filler. After lunch we went south on the last twelve miles of bad road, eight of them far and away the most difficult driving experienced. Innumerable corners were so sharp and narrow they had to be taken on second gear, remembering that if you gave the left mudguard too much margin off the wall you might drop the right rear wheel into the ditch. Some much needed passing places were being built, but to-day we met,no one. The slimy road made it a trying drive, but we touched nothing.

Modern cars with their poor view are not easy to drive on a road like this, and the more extreme forms are a serious nuisance. More than once I have had to get out to assist drivers into a passing place. In one case the driver was so sunken that even at the sixth attempt he dared not turn his wheels sufficiently at the right time, into what appeared to him a sea of heather diving into peril. We never should have got past without man-handling his car, but for a weakness in the ditch which enabled me to drop in my near wheels and climb out again.

The following day a driver swore he had seen no passing place, but ran up his wrong side and invited me to try. There seemed an inch or two to spare so I biffed his mudguard, as neither of us could see the leading edge. Having since torn the flywheel casing when backing, I shudder to think how I got past finally. In spite of the cut bank I ran my off wheels on top somehow and drove past, the flywheel casing scraping off the edge, no doubt. Fifty yards ahead was a passing place, and very soon another !

The worst was over at the River Polly, where was one of the lonely wood and iron schools one sees as a sign of some houses in the neighbourhood. The problem of staffing these little Highland schools must be a very serious one, to which there is nothing to-day in England comparable. By now the clouds were breaking up and we had remarkable views of Au Stac, Cul Mor and Cul Beag. Once on the 9 foot road west to Achiltibuie we turned east and flew inland past Loch Lurgain, till we struck the road from Lochinver to Ullapool, then ran N. past Inchnadamph, a 50 mile round in all.

But at Inchnadamph the map showed that Traligill, coming from Ben More Assynt, disappeared in the ground. The afternoon was now glorious, so we sought and found the swallet, two miles up from the hotel. It took the whole beck under a low arch, but after 20 yards the cave narrowed and needed proper outfit to follow. The dry bed was followed down for quarter of a mile to a rising, and 200 yards lower the burn was joined by another rising.

The Cave of Smoo’ (Durness) is formed in Cambrian Limestone, the next stage less ancient than Torridbiiian, and a thin exposure of Cambrian quartzites and limestone runs’south to the head of Loch Assynt, where it widefis out a bit. I have since discovered, through Platten’s help, that half a mile above Traligill are two caves, Cave of Roaring, and Cave of Water, which seem worth attempting. The glen next south of Inchnadamph is dry for a mile and contains a powerful spring. It is called Allt nan Uamh (Cave Burn) and is well known to bone-diggers.

On Thursday, another day of really hot sunshine, we left Lochinver, passed through the two glens to the south so gloriously covered with birch woods, and made to-day more comfortable but still cautious going over the twelve bad miles into Ross-shire. Stac Polly and companions were glorious. By Loch Lurgain on the good road we stopped, and I went straight up the steep slopes by the gully direct to the W. top of the remarkable ridge of Stac Polly, 2,009. I was only 70 mins. though the last bit was up a slab and by a pretty climb among ” hot cross buns.” Again there was glorious heat and good visibility.

Stac Polly has grand crags at either end with stiff climbs on them but along the top is an easy scramble. The ridge is accessible at many points but the fine rocks along it must-offer many excellent short climbs and sporting pinnacles. I got back to the car after three hours, and though on top I felt good for another peak or two, in this land of island peaks it is difficult to make oneself drive on another four miles, get out, and start a second peak all over from almost sea level. Anyhow I failed miserably to tackle Cul Beag, just above the road, and’we went along into Ross, turned south to Ullapool and on through the magnificent woodlands stretching for miles up Loch Broom and beyond, up to 700 ft. above sea, almost to the fork of the Dundonnell road.

The Ullapool woods are not produced by a doubtful struggle with man and animals. Here there has been planting and one sees not only park land trees as at Tongue, but also many fine firs and pines. From the first sight of Loch Broom the well remembered forms of the Teallach peaks kept us company, where years ago Bell and I made first acquaintance with the weird piles of Torridonian rock. From the Dundonnell fork we tore along to-day over the wilderness on an excellent nine foot road past a single house, the Altguish Inn, across Ross-shire to Garve, a road along which years ago we had crawled and bumped from mound to mound and rock to rock, and been glad of the ancient motor, a pioneer of the buses, which bore us.

At Garve you get the best dinner in the Highlands, and that is saying something. Also at the foot of Ben Wyvis you have quite lost the strange Sutherland country and entered bh glens and among mountains of a more familiar type.

Contrast and contradiction were the impressions I carried away. The grand trees of Ullapool and Tongue, the dense natural woods of stout thick birches resembling those of the Sognefiord, but occurring only at long intervals, are very puzzling. I should hardly think man can have been responsible for a general destruction of trees. The temperature maps give the January temperature as that of West Wales and Somerset, but the July temperature as 30 less than that of the mass of Scotland, which in turn is 3° less than that of the South Coast (which is 30 less than London town). This would make the spring very prolonged, and a warm period for ripening seeds may be very uncertain. Trees may then grow well, but spread too slowly to gain ground unaided against animals in our geological age.

If Sutherland belonged to the State, it would be an ideal country for the erection of huts, and for the marking of routes. There the builder of a cairn would be a benefactor. At the time of the row over Lloyd George’s Land Valuation Bill,, the Duke who owns practically the whole county, I believe, offered it to the State in a sense, that is, the Treasury found that his retaining all the water rights made the offer of no value. It is a great pity no offer for complete purchase was made him, and the lands annexed to the Crown.

Like the Coolins, the west coast of Sutherland is one of the things to see in these islands. If you go, order rooms at one place at least or you may have to turn back to the east. The country is the fisherman’s, not yours, and he stops for weeks.