The Roman Wall of Hadrian

By G. T. Lowe

My first knowledge of the Roman Wall was derived from scanty references in school books on the histories of England and the Roman Empire. An article in Once a Week, Vol. V., 1861, entitled ” An Artist’s Ramble along the line of the Picts’ Wall,” aroused my interest, and I began to read more about this interesting relic of the Roman occupation of Britain. At last, at Whitsuntide, 1888, J. A. Green, H. Slater and I arranged to spend a week in exploring the Wall from end to end. We took for our guidance Jenkinson’s smaller guide and Dr. Bruce’s handbook, starting from Carlisle as the walk increases in interest as one approaches the western end.

The Roman Wall, once frequently called the Picts’ Wall, in its perfect state, was one of the most remarkable examples of military engineering in Europe. Even now, after a lapse of over 1,800 years, its despoiled remains tell in no feeble manner of its former strength and magnificence. It has generally been regarded as a barrier against the Picts of Caledonia, whose frequent inroads proved a terrible scourge to the inhabitants of Southern Britain, at that time becoming less warlike and self-reliant under the influence of the Roman rule. Added to this formidable menace, the Scots from Ireland made repeated attacks south of the great barrier.

Bede in his Ecclesiastical History (completed 731 A.D.) says that Severus was the builder of the rampart, which stretched from sea to sea with fortified camps, made of sods cut out of the earth and raised above the ground like a wall, having in front of it the ditch whence the sods were taken, and having strong stakes of wood fixed upon the top. He says also that the Britons built the Scottish Turf Wall after 410 A.D., and later with the temporary assistance of a Roman legion built a strong stone wall not far from the trench of Severus, eight feet in breadth and twelve in height. Bede’s dates and facts are very confused.

From the double nature of the fortified line, as represented by the Vallum. or earth wall, which consists mainly of three ramparts and a fosse, and by the Murus or stone wall, with a broad deep fosse running uniformly on the north side, many archaeologists hold the view that protection against the south was also an essential feature of the work. A more recent suggestion is that the Vallum is the older structure, and that the stone wall was erected at a later date, invasion from the north being the only reason for the existence of the fortifications. Around this phase of the question enthusiasts have disputed with the calmness and moderation characteristic of specialists.

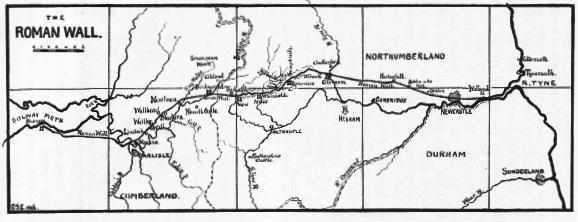

Stretching with undeviating persistency along the most impregnable line of natural defence, the Wall forms a huge bow from Bowness, on Solway Firth, to Wallsend-on-Tyne (Segedunum) a distance of over 70 miles. Between the Wall and the Vallum, and pursuing an easier course, was the great military road from Newcastle to Carlisle. From Sewingshields along the Nine Nicks of Thirlwall, an undulating series of precipitous basaltic cliffs, running some distance north of the most direct line across the isthmus, induced the military engineers to carry the structure along their verge, thus adding enormously to the strength of the barrier.

That the forts were in existence before the Wall is evident from the fact that, where the latter is built up to continue the north face of some forts, the rounded corners of the fort do not fall in with the line of the Wall, as may be seen at Borcovicium, while in the case of Cilurnum the Wall actually meets the ramparts some distance from the corner. In several instances forts lie to the north or south of the wall, entirely separated from it, as at Vindolana, the present Chesterholm, and these are believed to be part of the first chain of forts set up by Agricola.

Neglected and deserted for nearly 1,500 years, its well dressed stones have been utilized by generations of dwellers in its neighbourhood for the construction of castle, peel and homestead, until the extremities of the Wall have practically disappeared, although the fosse may still show traces of its former course. In the central portion, however, the existing remains are such as to enable the wanderer along its line to reconstruct in imagination the ancient rampart in much of its original form. Careful observations, assisted by excavations, have given us a clear conception of this truly interesting monument of the Roman occupation.

The more easily accessible forts are frequently visited, but few care to undertake to follow the whole line from sea to sea. This excursion is one to be strongly recommended, not only for the benefits to be derived from the exercise, but from the intellectual advantages. To see these time honoured remains in situ, to clothe the dry bones of history with fact, is to live again in the past, and to give birth to a desire to know more of the greatest nation of warriors and statesmen the world has ever known.

In following the Wall it is advisable to trace its course from west to east, as the interest in the relic is augmented by the gradually increasing importance of the remains.

The Wall was built of carefully dressed stones, generally about eight by ten inches, resting on a double course of larger stones which projected a few inches on either side of the upper portion. The space between these facing stones was filled in with rough concrete composed of small stones and excellent lime, as existing fragments testify. It was probably about eighteen feet high, and below the parapet from six to eight feet thick. The narrowest portions are found where the Wall traverses the steep heights in the middle of its course. The north face of the Wall is continuous, but the breadth seems to have been deliberately reduced during construction from eight to six feet.

At intervals of a Roman mile (about 1,618 yards) small gateway forts (milecastles) were placed, having two entrances, one to the north and the other to the south. Between each two milecastles were two small watch-towers, about two furlongs apart. So close were these sentry-towers that an alarm raised at any point could be passed from one to the other with great rapidity, thus enabling attacking parties to issue from the gates. In addition to these milecastles and turrets there were fourteen larger forts with barracks, varying in extent from three to five acres, situated at convenient positions along the Wall, usually about four miles apart and one at each end. They were quadrangular in form and rounded at the corners.

From the Notitia, compiled about the beginning of the fifth century, which is a kind of army list of the Roman Empire, a list of the prefects and tribunes of the cohorts located along the Roman Wall can be obtained. From this list, by comparison with inscriptions found on the spot, the names of many of the forts have been ascertainedwith absolute certainty. The number of these stations actually connected with the Wall was sixteen out of the twenty-three enumerated in the Notitia, the remainder being supporting stations north or south of it, among them,–Bewcastle, Castra Exploratorum (north of Longtown) and Birrens on the north, Chesterholm on the south.

It is convenient to consider the Wall in three distinct parts :–I.the stone wall or murus with the fosse to the north ; II. the earth wall or Vallum on the south side of the stone wall; and III. the stations, roads and habitations which would invariably spring up in the vicinity of the great camps. For the most part the Vallum and stone wall run within a few yards of each other right across the country; but in the central portion, where the Wall is carried to the north to take advantage of the high ridges, the space is much greater, approaching in one instance to half-a-mile.

And now one naturally asks whom shall we credit with the authorship of the fortification! Undoubtedly Agricola led the way when he built many of the forts across the isthmus afterwards traversed by the Wall, Modern excavation has shown definitely that the Vallum and forts mark the line first held, but just as definitely that the stone Wall was built in Hadrian’s reign, and restored by Severus, and again by Theodosius. The most recent theory, set out in Mr. F. G. Simpson’s lectures in Leeds (1934), is that the Vallum was constructed in Trajan’s reign, and the failure to hold the line is related to the destruction of the Ninth Legion. Hadrian landed in Britain A.D. 122 and died A.D. 138; the Wall was probably finished by 127 A.D.

In the course of two rambles along the Roman Wall, in one of which we traced the whole course from the Solway to Wallsend, we had ample opportunities of examining the principal points of interest. It is instructive to notice along the route how the place-names are significant of the existence of the Wall, as a cursory examination of the map will instantly confirm.

From Carlisle to Bowness the traces of the Wall are entirely absent, though the fosse gives feeble proofs of its former existence. To the east of Carlisle the first indications are to be observed in Drawdykes Castle and the peel at Linstock. The stones used in their construction are unmistakable, and make clear to the most careless observer the fate of the Wall. Such a convenient quarry could not be overlooked. Now, after 1,800 years, it is marvellous that so much of the original structure remains. From Wallby to Bleatarn the fosse is distinctly traceable on the left to the north. About a mile from Bleatarn the ditch passes through some gardens at Old Wall. Here a villager showed us a small stone nearly eleven inches long and nine broad, bearing an inscription to the century of Julius Tertullianus of the second legion. The stone was in the outer wall on the east side of a dilapidated hut near the end of the village.

After walking about half a mile in the fosse, we passed through Irthington and stopped at Cambeck Bridge for refreshments, and then went through the park by Castlesteads, which is probably the Petriana of the Notitia, to Walton. Westward of Amboglanna, [1] Burdoswald, no inscriptions have been found to enable us to identify the stations with the stations of the Notitia. Until one does turn up we must be contented to take the order of the list from Amboglanna and trust to its accuracy.

On the hills beyond the Kingswater the fosse can be traced for a great distance. After crossing the stream we found a long heap of stones under a hedge, which indicated the site of the Wall. Before reaching Garthside Farm several detached portions of the Wall from three to four feet high, considerably grass-grown, appeared; the fosse was well marked and regular. Many of the portions were without facing stones, but showed rubble and lime. Below Craggle Hill, in the south-east corner of a field, we found an unfaced bit nearly six feet high. The lime was good, showing white and clear. In the next field, at the bottom, another piece, seven feet high, was observed. On Hare Hill the fosse was magnificent.

The view looking back embraced the Solway, Carlisle, Skiddaw, Blencathra and the undulating country south of the Cheviots. A little to the south are Lanercost Priory and Naworth Castle.

At Banksburn the highest existing portion of the Wall is found in a garden by the side of the brook. It stands nine feet ten inches high, but had been deprived of its facing stones. It has, however, been refaced to keep it up.

Nearing Burdoswald the Wall appears on the south of the road in good preservation for a long distance, over seven feet thick and nearly six feet high. This fort, the Roman Amboglanna, is the largest on the line, being five and a half acres in extent, exceeding Chesters and Housesteads. It is situated behind a farmhouse immediately above the steep right bank of the Irthing. The place is typical of the rest. Looking out of the west gate the Wall on the right is six feet high, and on the left seven feet. The south-west corner is very high and solid, with the foundation stones very plain. The south entrance is broken down. The east Wall is almost gone, but over a modern wall the best gate is still to be seen, with two side guard-chambers. The walls are nearly eight feet high, with the remains of ornamental capitals. The pivot holes for the gates are very good ; there are two curved stones among the débris nearly two feet across, which probably formed portions of the arches.

A rough heap outside continues the Wall to a part of the foundation stones overhanging the Irthing, which, in the present state of the precipitous bank, causes one to wonder how the Wall was continued to the river, and to the bridge which must have crossed it. Several more mounds and portions of courses behind the vicarage garden next appear. Near the railway station there are traces of the existence of a milecastle. Next[2] Thirlwall Castle, built of stones from the Wall, is reached. At the back of an outhouse close to the stream at Holmhead, and built into the wall wrong way up, is an inscribed stone—CIVITAS DUMNONI. Up the hill the fosse is in splendid condition, and by the quarries the Wall is three or four courses high. The prospect along this portion overlooking Spade Adam Waste is wild, and until Carrow is passed the route lies along the most perfect and picturesque part of the Wall.

From Magna (Carvoran), one can walk on the top of the Wall, which in some instances is over six feet high, in perfect courses. Much of the first part is among boulders and a thick growth of trees. Passing an excavation about twelve feet square we noticed the fosse was absent, and the configuration of the country shows no need for this precaution, which, however, appears at every point where the natural protection is inadequate. , Over the Nine Nicks of Thirlwall the Wall rigorously pursues its course on their precipitous sides to Æsica (Great Chesters), a large fort indicated by high grass-grown mounds. At this point the rampart may be left, and at Haltwhistle, about two miles south, convenient accommodation is to be found. Resuming the journey, Cawfields milecastle, beyond the Caw Burn, is next reached, and the Wall shows in courses and mounds over Whinshields to the pretty group of Northumbrian lakes. Before reaching Crag Lough over Whinshields (1,230 feet), the middle and highest part of the Wall is passed. Nearly to the top of the crag the Wall is in splendid condition, and the sharp angles formed by it as it follows the contour of the edges are remarkably interesting,” On the cliff we stopped for a long rest and thorough enjoyment of the varied scene. The pretty little mere at our feet was dotted with waterfowl, and in the crevices of the rocks dwelt jackdaws, rockdoves, starlings and other birds.

On the next hill, after leaving the lake, is Hodbank Farm, where a visitors’ book is to be seen, given by the great antiquarian, Dr. Bruce, in 1856. He at the same time presented them with two of his works, which have since been borrowed.—Well, I need say no more ! The farm is beautifully situated, and affords a delightful and convenient resting-place for visitors.

From Hodbank we walked on the top of the Wall, which is here five feet high and over six feet wide, for a considerable distance. A little before the long plantation which terminates in Housesteads a grand milecastle is passed, with the northern wall over nine feet high; the southern doorway is broken down. Housesteads, the Borcovicium of the Romans, is a most interesting fort, magnificently situated on the brow of a hill, which, on its southern slope, shows traces of a considerable number of exterior buildings, the site of a town which had grown about the station. At some points the walls are over nine feet high. The western gateway is in excellent condition, with square columns standing, and two guard-rooms on each side about ten feet square. It has been reduced to half its width by closing the northern half of the outer and the southern half of the inner gate, When the garrisons were reduced this expedient was adopted at most of the camps, or it may have been owing to the lack of use. Bases of columns and other curious blocks of stone lie around the southern entrance. Rut-marks, as is often the case, caused by the chariot wheels, are plainly worn into the sill-stones of the gateways. The width of these ruts, 4 ft. 8½ in., is precisely the same as those to be seen in the narrow streets of Pompeii. The Pompeian streets surprised me not a little, and the high stepping-stones seemed to block vehicular traffic entirely. Probably their horses were inferior in size to our modern breed. It is noteworthy that this measurement exactly agrees with the gauge of the modern railway track, if it is correct.

The Wall, on leaving the station, is nearly eight feet wide and at the bottom of the valley is broken by a gap with large stones on each side, and to the south there are traces of guard-rooms. This was, no doubt, a more convenient entrance to the fort and town on the hill above, or it may have given egress to the amphitheatre supposed to have existed on the site of a hollow immediately to the north of this lower portal. Up to the small plantation the Wall is good, then it disappears, but by heaps of rubble it may be followed to Sewingshields.

It is an interesting variation to walk along the foot of the basaltic cliffs from Sewingshields to Borcovicium. The additional security obtained by leading the Wall to the north, along the verge of the precipices, is apparent.

With the exception of the Chesters remains the most interesting, and certainly the wildest part of the Wall, is now left behind. Undulating hillocks succeed, steep towards the north, then a recently excavated milecastle, with gateway and guard-rooms very plain. Several more castles were indicated by grassy mounds, and at Carrow we stopped to examine Procolitia, on the south side of the present high road. Carrowburgh is a dreary-looking station, with grass-grown ramparts, and the ruins of the gateways plainly appearing. The antiquarian knowledge of a local farmer led him, in a season of drought, to search here for water, and he was rewarded by the discovery of the ancient Roman well which on examination yielded a remarkable quantity of coins, altars, carved stones, Roman pearls, etc.

A little further on, and about a mile from Walwick, there are some fine pieces of the Wall and ditch. In one instance the former is over eight feet high, and remarkably solid and strong. The top is covered with a thick growth of bushes. The change in the character of the scenery is now very noticeable, cultivated fields and thick leafy woods replacing the wild rugged moorland. After passing Walwick, at the bottom of the hill Chesters is reached, at one time the residence of the late Mr. John Clayton, who has done more than any other man to preserve and make known the relics of the finest monument of the Roman occupation of Britain. In the road going down the hill to the entrance the foundations of the Wall were very clear in the present high road.

Permission being readily and courteously granted, we examined the numerous altars, inscribed stones, ear-rings, bones, pieces of pottery, etc., in the museum and behind the house and then proceeded to the park in front to inspect the remains of the Roman Cilurnum, which covered an area of five and a quarter acres, coming next to Amboglanna in size.

The ruins are nearly all exposed and free from earth accumulations, and present the most perfect examples of the buildings of the larger Roman forts. The Forum occupied the centre and at the south end of the enclosure is a vaulted chamber in good preservation, the aerarium or treasury of the station. Near the centre of the eastern wall was the praetorium or commander’s quarters. The hypocaust, blackened by smoke, and formerly yielding quantities of soot, is in an almost perfect state. The slabs of stone which formed the floors of the rooms are in position. Close to the river a series of seven arched niches, in good preservation, is noteworthy, and the building is clearly recognized as baths. At this point the North Tyne was crossed by a bridge of considerable size, as is evinced by the remains of the buttresses on the banks and the piers in the river bed. On the left bank the river has receded and a large mound of earth intervenes between the buttress and the stream. The lewis holes and grooves for the iron binders are clearly defined. One curious piece of stone, over a yard long, has the appearance of an axle-tree, with the holes round the centre. When the bridge was perfect it must have been a noble example of architectural skill.

Tired, yet thoroughly pleased with our day, we turned into the ” George,” a comfortable hostelry facing the lovely river.

Between Chollerford and Newcastle few obvious traces of the Wall are to be seen. Here and there the highroad passes directly over the foundation stones. This is especially noticeable before reaching the Errington Arms, and after heavy rain the stones used to be exceedingly plain.

At Heddon-on-the-Wall a long strip covered with a thorn hedge appears on the right of the road and just over the hill there is another piece nearly four feet high with the remains of a milecastle. The winding Tyne is now seen away to the south-east and a canopy of smoke indicates the proximity of a large industrial centre.

At Dene House, two miles past Heddon, in the corner of a garden close to the road, is a heap of stones which have formed the columns of the gates of a milecastle. Next, at Denton Burn, there are two irregular mounds between three and four feet high, surrounded by a wooden railing.

Of course, in addition to the remains enumerated in this brief outline, there are many less conspicuous which the keen antiquarian has disclosed, and to those who wish to have an exhaustive account of these I would suggest a study of Dr. Bruce’s large work and, for actual use on the walk, the handbook. Even at Wallsend traces still linger.

A few general remarks must terminate this account. Each of the forts was occupied by a number of soldiers varying from 600 to 1000, so that the whole garrison, consisting of cohorts of various nationalities, was probably about 12,000. In many places along the Wall specimens of rough inscriptions are still to be found, notably at the quarries on Fallowfield Fell, near Chollerford, at Coome Crag and at the Written Crag, in the glen of the river Gelt, near Brampton.

As will be gathered the central portion is in the most perfect preservation and this it undoubtedly owes to its wild and isolated situation. Thanks to the exertions of the Earl of Carlisle, the late Mr. John Clayton and others, the mutilation of the Wall has almost ceased and it is to be sincerely hoped that what remains of this valuable relic will be preserved from the destructive propensities of the passing vandal and the quarrying by the immediate inhabitants, ignorant of its antiquarian importance. Finally, a new era may be said to have opened for the Roman Wall, for now, careful and indefatigable attention is being devoted to its study and preservation, notably by the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-on-Tyne, whose journals contain notes on the most recent excavations and the consequent theories advanced.

1. Oswald’s Burgh-Burdoswald or Birdoswald.

2. A.S. Thirl-ian = to penetrate. Said to be where the Caledonians first hurled down the wall.