Six Days In Dauphiné

By F. Oakes Smith.

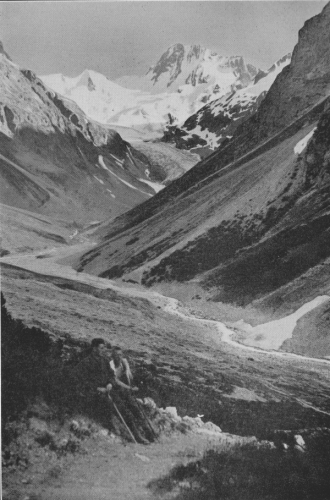

The first day found us at Ailefroide in delicious alpine environment, at the junction of the St. Pierre and de Celse torrents, Eastern Dauphiné. Thrust into the outhouse of an hotel at the call of later but wealthier patrons, we slept late, lost to the beauties of the morning. The day was an easy one as we were bound only for the Cézanne hut, one and a half hours up the valley, at the foot of the converging Glaciers Blanc and Noir. Bathing, sun and water—the kill-time of the Alps—passed the time quickly enough and the afternoon saw us trudging up to the hut.

It is small, much too small for the three streams of climbers converging on to it, but we were early arrivals and had the place to ourselves until evening. Major operations on the stove—which involved lifting it bodily outside the building—and on the preparation of foodstuffs, resulted in a meal. With bunks reserved we wandered on comfortably up the valley and considered the precipices of the Fifre and the Barre des Écrins.

The hut was quitted at 3 a.m., a late hour in view of the severity of the work in front of us, and the Glacier Noir was followed. It is completely covered for half its length with the rubbish of countless stone avalanches. A longitudinal moraine unbroken for fully two miles makes an easy way up its right side to the basin of the glacier. In one hour of splendid going, one reaches the foot of the Couloir des Avalanches. The slope, frozen hard, led to the foot of the bergschrund. The intention was that it should be crossed, the face of the Fifre on the left gained, and thence a first ascent forced up a couloir to the right of the Couloir du Brèche Nord, which lies further to the left and leads to the Brèche Nord du Fifre.

The schrund turned us away from its right flank where it was lowest, some twenty feet high. An uncomfortable half-hour or more was passed, for the whole area was covered thickly with powdered stone. Already the sun had reddened the ruinous mass of the Écrins straight up above and streamlets from melted snow were splashing down. The rocks on the left extremity were finally climbed, and time it was that we left the unhealthy place.

For twelve hours we climbed hard and the climbing was consistently that of a straight British severe. The couloirs were themselves about forty-five degrees and the snow was frozen hard. At 3,400 m. the right side of a névé was reached. It lurched into space and was circumvented on the right to avoid falling snow and stones. Two feet on our right fell the vertical wall of the Fifre, to bury its foot in the Couloir des Avalanches. The snow lay shallow on the scree-strewn rock, but the passage along the edge of this card pack was mercifully short. A diminutive crevasse was followed to the south toward the Col du Brèche Nord on our left.

Above, we made a long and serious attempt to reach the summit direct. A second small névé was crossed, obviously highly unsafe. Its foundation was again sloping slabs covered with loose stones and a light mantle of snow. The whole surface was ready to slither and there were belays nowhere. We wanted them badly. The top of the slope was reached and, full of hope, we went round the buttress to the right again to a gully. The top of the mountain was visible now, only two or three hundred feet above us, crowning an unclimbable wall. There was the gully at last. It had a slope of something like seventy degrees, but just as rotten as it was possible to imagine. Every spike of rock, and there were hundreds, leaned outwards and leered drunkenly down at us.It was hopeless and we knew it.

The time was now 4.30 p.m. and to descend the way we had come was out of the question. The one thing only to do was to descend slightly and traverse to the Couloir du Brèche Nord, mount it if we could to the Brèche, and descend by the south-west slope of the mountain to the Temple Hut. Therefore had we the immense pleasure of descending the nerve-racking slope we had mounted. The traverse looked as if it might go, and go it had to!

We reached the foot of the final 30 ft. of the couloir, which narrows down to a chimney. Both walls were covered with clear ice, and the chimney itself was capped with a cornice. The lead was magnificent and this couloir climbed for but the third time. The summit lay at hand up some easy rock on our right.

We were now in a less precarious position, but it was 6 p.m., and we turned and fled down a wide gully which offered. We were still in the gully when the last sunset fires flamed and burnt out. At 8 p.m. we reached its foot and gazed into the hostile maw. The Vallon de la Pilatte Glacier was hundreds of feet below and our spare alpine line was insufficient to use en rappel. Vainly we looked for a ledge where we could suffer the night in reasonable discomfort. There was nothing, and no light in which to go looking for non-existent lairs—of the kind we wanted anyhow. A number of jammed chock-stones in the snow-filled gully offered the only hospitality, and one hour’s chopping and scraping laid open a little sconce, five feet high and four feet square at the base. Firmly tied on to a belayed rope, we crept into our hole like four rats. Two of us taking the view that sleep would lower dangerously the vitality, declared against it. After we had made an intolerable effort to lie two deep, the two had the opportunity of practising their undoubtedly correct conviction by standing in a graceful curve with their backs to the ice all night. Their heads stuck out like giraffes against the stars. This ought to have been funny but the time was definitely not one for such humour, which would not have been appreciated. Thoughts wandered in strange realms that night.

Snow fell slightly throughout our sullen vigil. Spectral clouds, fugitives from uneasy gusts, swept away the cold radiance of the stars, only for it to return, flashing brilliantly through the thinning veils. Venus burned as never she has burned to the dwellers on the plains. Winthrop Young, I believe it is, describes the faint purple shadow cast on the snow in her light. The planet is superb.

Fortunately for the sleepers, the cold was not intense. The night dragged along. The wall and bed of the cave soon became saturated with water which had melted during the day and was now seeping down the bed of the gully. It wetted everything, stopped the cigarette-clock with its quarter-hourly solace, and then froze. The stars began to fade a little at 4.30, and little by little the ghostly glaciers were linked up as the darker rock ribs and buttresses took form. The shadowy outlines of the peaks became defined and soared lightly until they touched the sun’s fire. I have a recollection—possibly not unnaturally—that the sunrise was unusually beautiful and soothing. The Val de Vénéon was brimming with a sombre mist untouched yet by the rising sun. Fugitive pennons of diaphanous mist arising from the slaty-hued depths were diffused with the morning gold of the sun. They floated round the glittering snow peaks, disintegrated, and disappeared against the reds and azures of the sky. The precipices and virgin hanging glaciers spoke not yet. The silence was absolute and the scene perfection.

One or two dots below on the glacier came into sight: a late caravan for the Ecrins. We yelled; a pause ; then we saw the dots stop. Again a pause; and then an answering call came thinly up to us. It was immensely cheering.

Slight frost-bite was patiently rubbed out. At five we rattled, or anyway, creaked away to the lists, our armourplating firmly riveted in place. I suppose we looked as if we were in the throes of acute rheumatism. The contour was followed round the south-west buttress of the Fifre towards the higher slope of the glacier, and a subsidiary gully was reached after a short spell of climbing. An abseil took us then to the longed-for slope. The doubled belay rope would not be recalled and back one went, unhooked it and climbed down, chiefly by avoiding holding on to anything for long. The wall was bulgy with disintegrated plates leaning outwards. A grand feeling it was to get our feet on that glacier at last. The axe fairly whistled its way down the three hundred yards of steps—for we were without crampons. Little we should have cared if there had been a half-mile of such slope. The schrund was jumped and within an hour we were basking in the hot sun on the little sward by the Temple Hut spring; thirty-six hours after setting out.

We overhauled our supplies: a few bits of chocolate and wet biscuit pulp. The biscuit was divided to a drop. An hour’s sleep by the trackside righted matters and the party ambled down to La Bérarde after a Parthian glimpse at the shining steeps of gold and snow.

An off-day, or rather two-thirds of one, sufficed to put us in fettle and once again we left for the Temple Hut. It lies but two hot hours from the village. The slope faces south-west and is covered with scrub. Our quest on the morrow was the Barre des Écrins, the highest oi the Dauphiné. It is a grand mass and its glacier is dwarfed to a mere label stuck high up on its side.

The hut was left at 3.15 a.m. and we followed the fine sweeping curves easily and steadily upwards. A broad snow aréte circling the bastion of the Fifre arose from the bosom of the Vallon Glacier and gave direct passage to the Col des Avalanches, from the south-western side. High up on the Fifre, we could see the speck of our bivouac of the night before. In three and a half hours after leaving the Refuge we reached the Col des Avalanches. We looked east. Arrayed before us were the peaks of the Eastern Dauphiné. On the right was the buttress of the Fifre, steep and broken, whereon is the ordinary south-west route. We turned to our left and after drinking and spilling good wine, eating tinned herring and bread, we crossed the snow to the foot of the Barre and to a small couloir. The rocks on the right are climbed after a step over the crevasse. In the main they consist of two steep and completely enjoyable slabs with adequate holds. High up, the second becomes almost vertical, slippery, and blotched with yellow, somewhat suggestive of an oily leer. They are climbable if free from ice but a short steel cable hanging down saves time. The correct route then crosses to the right and after a delicate fifty foot climb on straight-up rock we spotted the right route crossing below us. A traverse of nice balances on bronze-coloured plaques took us on to it, and led to the Couloir Champeaux. A streamlet falls here during the afternoon with the result that the gully is filled with hard clear ice. That is crossed and a long rock aréte followed: grand easy work in the thrice-blessed morning sun. The peak seemed a colossus in its vast reach, pinnacle on pinnacle, clear lines against the purest and serenest of blues. This was the first wholly fine day we had had and we cherished every minute of it.

The Glacier des Écrins is crossed along its upper section and the great couloir reached. The snow had become unpleasantly soft but seemed sufficiently consolidated. The right edge of the couloir was taken to avoid the risk of avalanche from the cornice and subsidiary gullies above. A wise precaution, for with a hiss,a malicious little avalanche buried the rope between us whilst we were crossing one after the other. Ultimately one is able to take to the rocks on the right for the final section. The head of the gully was hung over with an enormous flaked cornice but these rocks gave us a safe route to the twin summits.

The crest of the Barre is a long ridge, each end higher than the centre. The ends form the culminating East summit 4,103 m., which we were approaching, and the West, T Pic Lory, 4,083 m., to which we passed. The reverse side, the North of the mountain, is glistening ice-slope, exceedingly steep. Although, I believe, there is a route up it, the normal descent of the mountain is made by this traverse to the Pic Lory, by following the aréte and leaving it before reaching the Dome de Neige, 3,980 m. The position is entrancing, for in places the ridge is only a knife-edge which one can sit astride, one leg over the Vallon Glacier many thousands of feet nigh sheer below, and under the right foot the Glacier Blanc, a vast circle of ice and snow without rock outcrop to blemish. It is spotless. The vast Mont Blanc Massif, Grand Combin, the Valaisan group, Matterhorn, and Monte Rosa, spanned the whole northern horizon, over fifty miles away. The burnt Italian Maritime Alps stretched to the eastern horizon in all their naked lifelessness. On the south horizon were the plains of Savoy. Nearer lay the Grande Ruine, presenting turret after turret, the square Zsigmondy face and Glacier Carré of the Meije, the Pelvoux bloc, the spread of the sweeping pinions of the Ailefroide, and Les Bans.

Our reveries over a bite of food were broken by the roar of an avalanche, and a cold wind from the North drove us from the summit down the slope. The inevitable schrund separated the summit snow from the Glacier Blanc, and after a climb down to its upper lip the six feet separating it from the lower were jumped. We bore off across the face of the east side, only very gradually descending. It was essential to pass above the ice-cliffs which hung over the main glacier. From here we zig-zagged to their base between the unsteady ice-walls. The track of a recent avalanche was passed at the double. There remained several hours’ distance to the Cézanne hut, so we bent our heads and trudged on through the soft snow, past the Caron hut under the shoulder of the Roche Faurio, then skirted the tumbled base of the glacier as it turns over into the St. Pierre valley. On we plodded to the Tuckett hut—a veritable barn. The way, lost awhile amidst the shifting moraine, turns sharp right across the glacier end. The unwary plunges straight on and inquisitive wild things want to know what the lumbering thing is doing in their domain. Marmots inspect and then skip away under some boulder or other. A quarter-mile precipice however, with a View down on to the Cézanne hut, a mere speck, shews him conclusively the error of his way and he returns to overtake his lazy but wary brethren, already half-way down to the Refuge under the Grande Sagne at at the other side of the gorge. Its black polished sides warn away most folk, who have but a single thought—the Cézanne Refuge and its bunks.

The hut scenically is beautifully placed. It is built at the foot ofthe gaunt rock slopes, at its sides and back the protective pine-wood, and beyond rise the Massifs of the Dauphiné, Pelvoux and Les Écrins. The snouts of the Glaciers Blanc and Noir overhang the high meadow. The smooth ravine of the Glacier Blanc shows that the glacier has yielded ground to his mighty foe.

One party of men and women filled the hut but contrived most generously to make room for us. One expects as much consideration as cleanliness in many a French Alpine hut, but one experiences nothing but kindness and cheerfulness from the Hauts Montagnards of the Club Alpin Francais. There was even a bolster fight that Saturday night.

We rose on Sunday at the Christian hour of eight o’clock or so, and went out into sparkling air. It was delicious to laze on the meadow with the runnels each side carrying their icy water. The stove—the chimney of which had been apparently carefully removed by a neighbouring peasant,to encourage trade in lean times and discourage the use of pine-wood—was bullied into giving out warmth and a disproportionate amount of smoke. Breakfast and bathing as usual filled the morning and mountaineers are as near to heaven in these spells of leisure as they are likely to ascend.

The approach of midday sent us with reluctance down the valley to the Ailefroide Hotel and filthy swarms of flies. We had, and paid for in full, a satisfactory dinner. The flies made a valiant effort to turn our stomachs: they crawled on everything and in scores.

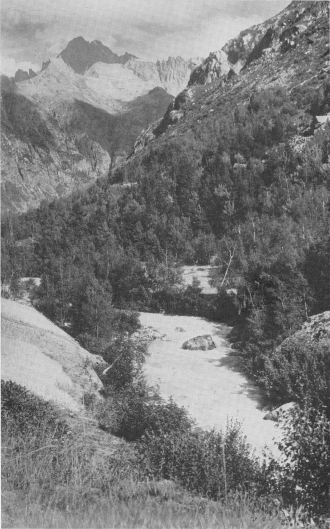

Mountaineers are not welcome. The flies, carelessness which ruined a suit—a serious matter—and the unsympathetic management, made us glad to leave. A sun-speckled dell with the mountains peering over, is the only memory I care to preserve. It had a small intake, scoured out by the backwash of the torrent whose voice rose rich and deep. The boulders under the seething waters could be heard speaking gutturally as they were driven and pounded along in that mad rush. Forty winks completed the spell, broken by a wicked horsefly. He bit through a thick stocking.

We left just after four in the afternoon for the Selle Refuge. The Way lies up the Torrent de Celse Nière and soon becomes rough and steep. High up the valley one has to cross over to the south side to mount a steep snow slope and pass over a shoulder of the cliff which blocks the head of the valley. The torrent here plunges into a great throat behind the thin dry lip of the precipice, whence drifts a light cloud of spray. The river reappears from under a snow arch over which we had passed, at the foot of the cliff. The force is shattering but it spends itself in the depths. The moraines lie here and the Sélé Glacier is close by.

The night was closing on us rapidly when we spied the hut perched under a protective buttress. In the gloom without a lantern it was something of a climb to reach the hut, for it lies above loose rock of perhaps 150 feet in height.

We had taken some four hours to rise the 1,300 m., for the Refuge lies at 2,700 m.

The interior was filled with the usual French guides, and dirt. The table ware was unusable as it was covered with grease., The chimney smoked dreadfully. The only coffee percolator was commandeered by them—for an early morning start. Altogether we were just as happy to leave the grease and fleas of the hut—we were all bitten more or less severely—as we had been to leave the inhospitality and flies of the hotel.

The cool sweet air before the dawn and the indescribable grandeur of the sunrise cleansed us mentally of our troubles and unkind expressed thoughts. The snow swept up before us to the south-west as if to join the sky. On the north, the Ailefroide for mile after mile turns round on its vast pinions. The resemblance is perfect and astounding. Tapered buttress after buttress runs up to the Pelvoux ridge, the wing-bone, to form feather after feather ; and the wing-bone joint and droop are exactly right.

We crossed to the south side of the glacier and after strapping on crampons ascended the frozen steep snow easily. The glacier wheels to the west, steepens and breaks up into ice-cliffs and crevasses. By passing above on the left, one reaches the Col du Sélé.

The day’s work lay in front of us, and after a meal we moved off in the usual two strings. At our feet the rocks sank away to the upper reaches of the Glacier de la Pilatte. They were shattered, but by the use of two shallow parallel gullies, any danger from dislodged stones was eliminated. At the edge of the snow, crampons were remounted. The traverse under the ridge connecting the Boeufs Rouges with Les Bans was really steep and frozen hard. The slope was at least half a right angle and at the ice-falls vertical or overhanging. The frozen snow would have needed many hours of step cutting but with crampons we were able to walk across cutting but few. Ankles complained of the awkward strain, and the spicules of dislodged ice scuttled down with surprising acceleration, finally making one unnerving bound over the bergschrund below. One felt most insecure and feeble-ankled. The best of the traverse was the crossing of the final ice-cliff. The crevasse was fully 100 feet deep and it ran out into the overhanging cliff. Its extremity was bridged over with snow, but as it was cheesy there were four ice-axes belayed at this point ! All went well and by following a semi-circular route we gained the scintillating white ridge and the Col des Bans. This sharp corniced ridge led us to the foot of the rocks. A short clamber up snow-covered rock took us to a knob, clearly visible on the horizon from the hut below, where we dumped the sacks. Sardines were swallowed on lumps of chocolate, because that was all we had.

The kit was light, but we enjoyed the sheer bliss of climbing with none to the summit. We fairly shot up the tolerably sound rock—glorious climbing—and reached the summit in just one hour. Even impossible routes on the wall on our right were worked out in our exultant minds.

The view from Les Bans is that of the heart of the Dauphiné. In the north sweep the Meije, Écrins, and Ailefroide, and below is one of the two most riven and picturesque ice-rivers. We slept on the top, utterly content, for some period we wotted not. The hot sun, blue sky, white glacier and dark rock made a perfect tableau. We were the only blemishes, like so many nigger minstrels with sun-burnt faces ringed and smeared with white cream.

The descent to our pinnacle took three-quarters of an hour. On reaching the snow ridge the two strings roped together and this time went straight down the slope. It was excessively steep but went well. An airy jump of some eight feet landed us on to less steep ice and we joined the Col des Bans route, and zig-zagged in a series of chevrons to the foot of the Pilatte. The stony track from the Pilatte Refuge to La Bérarde passed slowly although it is a fine walk. Occasional glimpses of chamois against the skyline kept up one’s flagging interest until the village was reached. Two long mountain traverses had left us little the worse for wear.

The dinner that evening was suited to the occasion and the soft clean beds were as soft as we had wished them to be. On the morrow the ways of the four diverged—each to softness : a cabaret at Chambéry, and a river balcony at Grenoble and charming female company.