Three Summers In The Club

By S. H. Whitaker.

My first experience of pot-holing was the 1927 Whitsuntide Meet at G.G. Quite a number of new members were in camp by Fell Beck, and it had been decided that a good initiation would be to do the Flood Entrance. Those who didn’t wish to make the complete journey, and indeed the parties to do this had to be kept small, could get quite a good idea of what pot-holing was really like by helping to carry the tackle to the foot of the 150 ft. pitch, a journey which was made by six men from the Main Shaft in 35 minutes.

Early on Whit-Monday the surface party, consisting of Frankland, D. Burrow, and Hilton, let themselves down through the Narrow Gauge and started on their long crawl. They were given a considerable start before the G.G. party started down the Main Shaft. Even so a long wait of an hour or more at the Flood Pot was necessary, which was partly spent in tying together the 150 feet of ladder and preparing the tackle, until a pin point of light announced the presence of the surface party at the top of the pitch. The beam of an acetylene light at last picked up the paperdecorated end of the cord dropped by the surface party, and first the life-line and then the ladders were hauled to the top and fixed. The members of the surface party then changed places with H. S. and F. S. Booth, Taylor and myself, one man from the surface party coming down, then one man from the G.G. party going up, and so on.

Long shall I remember that ladder climb ; being new to the craft I had rushed the first part of the climb in order to get out of the water as soon as possible, consequently when a sharp knock on the head and a concentrated stream of water down my neck told me that I had come to the lip of the fall I was uncomfortably blown. As the pin point of light at the top seemed as far off as ever I tried stopping on the ladder to see if the pull on the life-line was any good ; it wasn’t, the Yorkshire Rambler at the top didn’t believe in doing another man’s work for him. I no longer rush long ladder pitches in the dark.

After the last man of the G.G. party had reached the top and recovered his breath, the ladders were lowered and the end of the life-line dropped down the pitch. The G.G. party having burnt its boats moved on to the next difficulty, or rather to the next place where the difficulties were more concentrated. This is a ladder pitch and the surface party had left the ladder complete with the life-line doubled over the top rung.

As the leader of our party seemed to find some difficulty in getting off this ladder, which was rather short, the top eight feet having to be climbed up the mooring line, a timidly expressed hope that this was not as hard work as it sounded brought down a typical pot-holing answer, and we learnt that we too would blow and pant had we to lead such a place with a rucksack.

The chief snag about it is that the party is afterwards encumbered by the ladder and line in passages along which one has difficulty in dragging oneself. A short way beyond this pitch a small waterfall is encountered about 12 ft. high, which has to be climbed direct and was led by Fred Booth.

Some time was lost in finding the proper exit to Cigarette Chamber, where strangely enough we found a pipe in quite a good state of repair. From Cigarette Chamber to the foot of the long squeeze is merely a long crawl, and our main difficulty was to find the proper place to start climbing this 40 ft. squeeze; we were engaged, in fact, in solving this problem when C. E. Burrow’s cheery voice hailed us from the top and under his direction we went on to the end of the passage where he let down a rope for us, which simplified our ascent very considerably.

The last of our problems, the Gauge, was overcome by each man removing all but an irreducible minimum of clothing, a stirrup being let down and used as a movable foothold, with vigorous help from Seaman at the top.

The Three Peaks.–The meet at Horton-in-Ribblesdale in July 1927 was well attended, but its official reason, a Midsummer night walk, seemed to lose some of its popularity, for only H.S. and F. S. Booth, DeLittle and myself turned out, although I believe another party did the round during the next day.

We were fortunate in our weather conditions for when we started at about nine on Saturday night there was hardly a cloud in the sky. We reached the cairn on the top of Penyghent in daylight to witness a remarkably fine sunset. It was not thought advisable to spend too long admiring this, but to get back to Horton as quickly as possible in order to take advantage of what light there was before it got really dark.

From Horton to Ribblehead is rather a monotonous tramp along the high road, but the time was found useful to discuss the details of a coming holiday in the Pyrenees.

The ascent of Whernside was more difficult, as a considerable amount of open country has to be crossed to reach the mountain from the main road, and at night a boulder and a stray sheep look very much alike, and the way is very much more difficult to find. However, Whernside is hard to miss, and at length we arrived at the top, where we had an encounter with a little sheep in a more pleasant form (mutton sandwiches).

From the top of Whernside we took a line due south and day was just dawning by the time we reached the Hill Inn. Ingleborough was attacked in a thick mist, and perhaps as a result of this we got too far round to the west and had some very steep clints to climb.

Over Simon Fell very frequent recourse to the compass was necessary, as at times on taking a bearing we found ourselves almost at right angles to our proper course, visibility being confined to about twenty yards.

Pyrenees.–A fortnight’s holiday at Vernet in the Pyrenees with the two Booths led to only one serious expedition, an attack on the Barbette, one of the peaks of the Canigou. To start with, except for the Canigou the district is all wrong, and secondly the inhabitants do not understand the requirements of mountaineers. Among its recommendations, however, are a glorious warm swimming bath, and a peculiar liqueur, ‘ Liqueur de Canigou’

We started our attempt on the Barbette at 4.30 a.m. one morning, first following the main road to Fillol to a point where a mountain track leads off to the right, marked by a signpost ‘Canigou 6 hrs.’ No anxiety was felt when this track was lost in the darkness; Belloc’s maxim for ramblers in the Pyrenees was not then fully appreciated (it soon got to be).

No serious attempt was made to find the path ; we merely continued up the valley where we thought it ought to be. On climbing a steep slope at the end of this valley we came across another track where we had our second breakfast, the early morning sun shining over the mountain into Spain making a beautiful background to the sardines and various interesting kinds of cheeses. We followed the path we had found until the main peaks of the mountain came into sight, and left it soon afterwards, as it appeared to have no connection with the top. We struck straight up the shoulder which seemed to offer the most direct way to the top. My next memories are of unbelievably steep scree and perfectly diabolical heat. It soon became obvious that we had gone wrong somewhere; however, it seemed preferable to go on rather than to lose the height we had already gained by going down and starting the difficult task of finding a path. We accordingly carried on and eventually reached the top very thirsty and very hot.

We tried to traverse from the top of the Barbette to the rnain peak, but the rotten rock made any such attempt unjustifiable. We were also anxious to get back to the nearest water, one of us having mistaken the complete water supply of the party for his own ration. The ascent had taught us the importance of keeping to the track and Belloc’s rule was religiously adhered to on the descent, with the result that we got back to Vernet in quite good time.

Lost Johns ’.–Two camps were run at Whitsuntide 1928, one at G.G. and the other at Lost Johns’. Several new long passages had been discovered in the latter, and it was hoped to follow some of these right to the end. Six of us assembled in the Camp at Leck Fell House on the Saturday afternoon and carried in a considerable amount of tackle in preparation for the first long day.

My chief memory of the pot is one of appalling mud beyond the Centipede Pot, and also the climb up the Centipede after a hard day. It seemed difficult to keep the life-line on the right side of the ladder, one of our men having a particularly bad time through not climbing round at the proper time.

Only three of us braved the mud below Centipede Pot on Whit-Monday, the other two arranging to meet us on our way back at its head, and help to carry out the tackle. All went well until a pitch, which we have since heard is the last but one, was reached where we found we were a ladder short. It was arranged that I should go to the top of the last ladder climb, let down the ladder used there on a line, and if possible go to sleep until I heard from the other two, when I was to let down the line, and haul up and fix the ladders in position again so that the other two could get up.

I did not go to sleep. Hilton going down the ladders first had gone on ahead to explore–nothing was heard of him for some time—the other man began to get anxious, and a loud cry of ‘ Jack ’ rent the air, and, as there was no response several more appeals followed. Some time elapsed before the missing man turned up, and we learnt that the passage went on to another vertical. The Editor then went down to see what he thought about going on, but the obvious conclusion was that we could get no further.

Soon after this I felt a tug on the line and I accordingly hauled up and fixed the ladder. Approaching Centipede Pot with three ladders, etc., the mud seemed thicker than ever. Truly the mud here is the worst feature of Lost Johns’.

I think we were all three very glad to meet the others at the top of the long climb, and the rest of the day was spent in getting all the tackle on the entrance side of all troubles, where it was dumped, each of us taking a light load back to camp, which we reached just as it was getting dark.

Tuesday dawned very wet and the morning was spent in yarning in the tents, Roberts and I going for a shot at Short Drop later.

We unfortunately turned up at the entrance to this hole without any dry matches and only one electric torch. The expedient of drying matches in one’s hair did not work, probably because the matches were too wet. We fancied that a crawl of about 200 yards would bring us into Gavel Pot, but we followed the windings of the passage with our single electric light for what must have been at least quarter of a mile without coming to any sign of the waterfall. As we wanted to strike camp the same day we did not persevere, but turned back and made for the entrance, having an exciting moment when we nearly lost the battery out of our lamp. Had we done this things might have been exceedingly awkward. My chief impression was the discovery of how very difficult it is to get along a low passage filled with every conceivable sort of obstacle, or so it seemed, without a light.

Skye.–A fortnight is not a very long time to do anything in Skye, especially if the fortnight has to include the journey there and back. The journey from Leeds to Mallaig is not one to be undertaken lightly, without an ample supply of provisions, as the long stop at Crianlarich, to enable passengers to get breakfast may, or may not, materialize. In our case it did not, and it was a hungry party of five climbers, Crossley, DeLittle, H. S. and F. S. Booth and myself, who rushed wildly out of the station refreshment room to the already moving train, the last man having just time to complete his purchase of a large bag of buns ; however a good lunch and tea were available on the Portree steamer. We eventually arrived at Glen Brittle at about 7.30 p.m.

Early next morning we made our way up the Coire Na Banachdich, intending to reach the top of Sgurr Dearg by way of the Window Buttress climb,probably the best,and certainly the most interesting,way to the summit of Sgurr Dearg. Graded in the S.M.C. Guide as a 3, it starts in a 40 ft. crack which is probably the most difficult pitch ; there is also another interesting pitch near the top, from which the climb gets its name of the Window Buttress.

From the top of this climb an easy scramble and walk leads to the summit of Sgurr Dearg, passing the inaccessible Pinnacle on the way. We climbed this pinnacle by the long east ridge, the wind, rain, and extreme coldness of the rocks making this ordinarily quite easy climb not without its difficulties.

To this day we have not even yet succeeded in coming to a decision as to what climb it was we tried first on Sron Na Ciche; the descriptions of the Cioch Direct fit it nearer than anything else, but whatever it was we had to turn back and eventually reached the top of the Cioch by means of the well defined terrace which crosses the face of Sron Na Ciche at a steep angle, and then by the very steep slab leading to the foot of the Cioch itself.

The second week of our holiday was spent at the Sligachan Hotel, the weather remaining exceedingly misty and wet, our first expedition, the Pinnacle Ridge of Sgurr Nan Gillean, being done in a thick mist. We were fortunate, however, in having one really beautiful day when we climbed the West Ridge of Sgurr Nan Gillean and along to the top of Am Bhasteir, whence we got a wonderful view of both Black and Red Coolins, and indeed, of many mountains on both the mainland and Outer Hebrides.

The climb from the top of Am Bhasteir to the top of the Bhasteir Tooth entails a descent of about eighty feet in which there is one interesting pitch, and then an easy scramble to the top of the Tooth. We climbed off the Tooth by Shadbolt’s Chimney and returned to Sligachan over Sgurr Bhasteir, getting another particularly fine view of the Red Coolins from the top.

There are some very interesting crags about half an hour’s walk from Sligachan, Eagle Crags, and a very pleasant day can be spent climbing there; but as the route entails crossing a fairly big tributary of the Red Burn, parties should remember that Coolin burns rise and become almost impassable very quickly in wet weather, and in such cases it is better to send a man across on a rope, as the human chain method has nothing but simplicity to recommend it.

Norway.—The question of going to Norway for the 1929 holiday was first broached on a trip to Doe Crags, Coniston. The snag seemed to be that most of us could only manage a fortnight, and this had to include travelling time. Good and faithful staff work by Robinson, who was unable to go at the last minute, elucidated the fact that, although the only available Fjord boat left Bergen the day before the steamer from Newcastle arrived, it was possible, by travelling overland via Voss and Stalheim, to catch this same Fjord boat at Gudvangen.

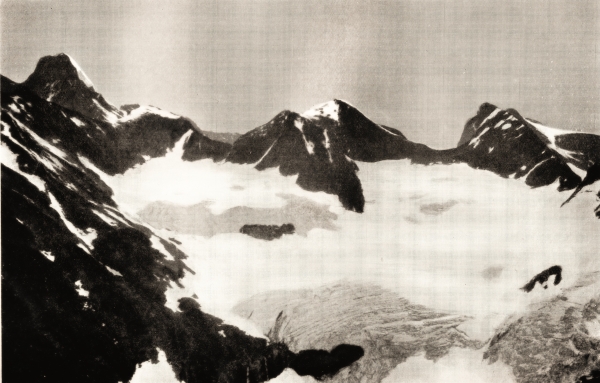

Our party,by some additions and subtractions, at length found its level at six. Creighton, Sale, Elliott, DeLittle, Fred Booth and myself, followed the itinerary previously mapped out by Robinson and arrived at Gudvangen in plenty of time to catch the Fjord boat to Skjolden. The walk up from Skjolden to the small hotel at Turtegrö proved valuable training for the more serious work ahead.

A 5 a.m. start was made next morning, in good weather, in an attempt to make the first ascent of the season of the Store Skagastölstind, the hut being reached about 8 a.m. Here a second breakfast was cooked and all the blankets taken out of the hut and spread on rocks to dry in the sun.

From the hut a steep snow slope was utilized, but this unfortunately involved us in scrambling up some nasty, greasy, steep slabs before another snow slope brought us to the foot of the main peak. From here we used Heftye’s traverse, which is a somewhat exposed traverse on good holds to the foot of an exposed difficult chimney, for the entrance of which a shoulder from one’s second is necessary. From the top of this chimney about 200 feet of rough scrambling lead to the top.

The same route for the descent was followed, with the exception that the slabs were cut out and we arrived back at the hut at about 8 p.m. Even with three blankets each, all our spare clothing, two Primus stoves, and six pipes going, we had a cold night and found another early start next morning for the Midt Maradalstind no hardship.

On looking at this ridge the night before we had seen a convenient snow filled gully leading on to a low part of the ridge and from thence the way along the ridge to the summit we hoped would go.

When ascending this gully next morning we took to some rocks on the side of the gully, which looked as though they might save us a long snow trudge, but in practice these rocks turned out to be more difficult than they looked, and as a consequence a good deal of time was wasted. In fact it soon became evident that if the peak was to be conquered that day, another night in the hut was inevitable and as our stock of provisions had by now run somewhat low, the wiser course seemed to be to go back to Turtegrö and do the peak later on.

The weather was too good to permit of an off day before something more was done, so another 5 a.m. start was made the next day for the traverse of the Soleitind, After some deliberation it was decided to tackle the main peak first, and then come back over the horseshoe to Turtegrö, taking in the two rock peaks on the way. The main snow peak went quite nicely, but the centre rock peak proved more troublesome, nobody in the party knowing the proper route from that side; two or three ways that seemed to offer possibilities were tried, but each one, in the end, had to be reluctantly abandoned. We did, however, succeed in forcing a way to the top of the smaller rock peak, by descending a snow slope a little way, then traversing and taking to the rocks. Our time for the traverse of the Soleitind from Turtegrö, back to Turtegrö, was 13 hours.

Our next trip was another attempt on the mountain that had turned us back on our second day, the Midt Maradalstind. This time we determined that any error in the commissariat department should be an error in the positive direction, not in the negative, consequently a pile of provisions was assembled in the hotel porch for dividing up into loads, sufficient, if the comments of the other people in the hotel were anything on which to judge, for at least a week. After afternoon tea on Sunday we strolled up leisurely to the hut in preparation for an early start next day.

This time we made the top of the snow gully in an hour and five minutes. We soon afterwards reached the point where we had turned back the first time, but the weather, which up to this point had been good, made a change for the worse, and the climb to the summit was made over difficult rocks in a partial blizzard, the return to the hut being particularly wet.

We had hoped to be able to go back to Turtegrö over the Dyrhaugstinder, but after waiting about all afternoon without seeing the weather get any better, we decided to go straight back that night. Having once made the decision we felt justified in really letting ourselves go on the provisions and reached Turtegrö about 8 p.m.

Not being so pressed for time on the return journey to Bergen, we were able to take the Fjord boat right through, a delightful trip across the North Sea making a fitting wind-up to a really splendid holiday.

LongKin.—Owing to bad weather in August this year, 1929, pot-holing in both Lost Johns’ and G.G. has been nil; also there do not seem to have been many private pot-holing expeditions organised for the smaller pots. One exception however, was Long Kin on Newby Moss.

For this it was arranged that a working party should turn up on the Saturday afternoon, carry up as much of the tackle as possible, and also rig the first two pitches.

Roberts, Fred Booth and myself accordingly met for lunch one Saturday at the Flying Horseshoe, Clapham. Six ladders, six ropes, candles, blocks, etc. were loaded into Roberts’ car and with Fred Booth sitting on the tackle in the back, and Roberts and I in front seats we started out for Newby Moss. The carrying up of all this tackle from the car to the pot was hot and thirsty work. It is interesting to note that the surface water round about the pot, whilst being excellent for acetylene lamps, is certainly not pleasant to drink.

Probably the best way to do this pot-hole is to rig both the first and second pitches from the surface. A good safe belay for the first pitch ladders was found, which brought the foot of the ladders to the extreme end of the first platform, about 70 ft. below the surface. The second pitch starts more or less directly at the other end of the platform :and about 10 ft. away from the first pitch ladders. We had heard tales of a man standing on the small chockstones for three quarters of an hour; if this was so, a good deal of weathering must have taken place, for it would be absolutely impossible now.

The ladders for the second pitch, 150 ft., were tied together and lowered until the top rung was only a few feet above the platform, then made fast on the surface ; the life-line for this pitch being also worked from this platform through a block attached to the surface.

The next day our party was augmented early by Sale, Gowing, and later by Burrow Taylor, C. E. Burrow and Brown, and the serious descent was made. The first and second pitches worked excellently (if the fact of the man stepping off the ladder at the bottom of the second pitch and stirring up a dead rabbit is taken as being irrelevant, which of course, it is). The greatest difficulty that this expedition had to face was undoubtedly to find a really satisfactory belay for the third and bottom pitch; the belay which eventually was found, however, proved extraordinarily satisfactory, because (by good luck) the surplus ladder at the bottom of the pitch could conveniently be utilized, without any further rigging, to descend a little final hole about 20 ft. deep.Minor accidents unfortunately prevented two of the party from making the full descent, but the presence of a large party pulling at the life-line at the top of the big pitch was very helpful to those coming up,

The journey down from the pot with nine men to carry the tackle was a delightful experience after the journey up.