Corsica In May

By The Editor

The visit of Smythe and Slingsby to the mountains of Corsica was responsible for the circulation of enthusiastic accounts of the island. Two things particularly attracted me-the first, a story that about the end of April a man could point to a cloud and say: “ That’s the last we shall see for four months.” After an Alpine season in which the weather, without being bad, contrived to effect the maximum of interference, the thought of a country in which one had not to worry about weather was irresistible. Smythe has since published his summing up thus : “ Bad Weather is in Corsica a sneak thief in the palace of King Sol, not a feared and despotic tyrant as in the Alps, nor a luckless institution as in Britain.” He is about right, but it did not work out quite as we expected, in fact the general tone of the many recent articles on Corsica is that there nothing does.

The second attraction was that unclimbed peaks could still be bagged, and as Smythe knew where these were, this settled it, and we arranged to go out in May, 1929. During the winter Brown joined in, but the idea of a personally conducted fortnight was rudely broken by Smythe’s taking up an office job like ordinary people, with the usual holidays.

Brown simply ridiculed any idea of giving up the expedition in face of the bother entailed. To a man who had wrestled in inadequate French with Arabic speaking Berbers who knew less, the difficulties of getting into camp in Corsica simply could not exist. So I turned to read up the books, and gradually it dawned on me that the serious climbing in Corsica is all in the group of Monte Cinto and Paglia Orba, and is all worked from one spot in the Val de Viro, or has been so far.

Had I known the sea voyages from Marseilles or Nice ran to 240 miles in 15 hours, or 150 miles in 10 hours, I should never have had anything to do with the venture. However, new boats have now been put on, and with ordinary luck the voyage, first class, is quite comfortable and reasonable. The time-tables are singularly confusing, but in the island the French have a simple one which shows a boat each day to one port or other. Ajaccio and Bastia alone concern the mountaineer, with Corte on the railway about half way between them.

We left Leeds early on 8th May, 1929, and all the way south noted that the trees were bare and backward. In Kent the fruit blossom was only in bud. It was the same for a hundred miles in France, till dusk came. Most trees were very bare, particularly the poplars, and the willows more backward than in England. But the thing that struck us most was that ten days before we had walked by Bishop Thornton and Sawley and seen the hedges a drift of blackthorn, and still far into France was much blackthorn without leaves.

We woke to another climate beyond Lyons. Here was that fortnight ahead—horse -chestnuts in full bloom. At Avignon poppies appeared and by the coast were a glorious show. By the sea we had entered upon summer. “A brilliant day and bare rocky country, vegetation surprising considering the thin covering on the limestone.” I can guess now what that vegetation was.

Beyond Marseilles we grew weary of endless vineyards and beastly bare grey olives. It seemed a country into which all food is imported and paid for by wine. Near Nice there was more woodland and rougher ground. The palms were a miserable untidy wreck, the effect of an unusual winter, we were told.

The day was so overpoweringly brilliant, and the sea so blue we must surely have discovered that Italian blue of which our Alpine reading had told us so much, and which we had looked for in vain. Some weeks later we knew we had merely hit one of the piercingly brilliant days which precede bad weather, or what stands there for bad weather. We never saw anything like it again.

From Nice we saw land faintly and a peak which was Paglia Orba.The crowd puzzled us much , so unlike it was to what we had expected. Finally I had a brain–wave–it was Ascension Day and a public holiday.

Friday we spent crossing, lost our beautiful blue by lunch time, saw some peaks above the clouds, never saw the famous view of Corsica, and reached Ajaccio in an English atmosphere with dense clouds low down on the hills. A French writer has described a winter in Corsica as a “ second summer.” Nothing is going to persuade me that Ajaccio does not have some severe weather. Never have I seen so many bedclothes. There were eight blankets and an eiderdown on my bed. Were the climate so equable as the books represent, the hotel would not have possessed the stuff, much less put it out.

Ajaccio we left by train at seven a.m., and learnt from some English people that the tall trees with brown rags of foliage, which annoyed us there and on the Riviera, were eucalyptus. It was summer by the sea, but as we climbed to three thousand feet through a country like the Lakes, with a scale and steepness not that of the Alps, we came to a region where the trees were a week or so behind England, yet with contradictions, for there were cherries set in a station garden. The Col di Vizzavona was cold and misty, but down near Corte we came to warmth again, with more turf and less of the heather–like maquis than we had seen on the west. At Corte we lunched (Hotel de la Paix, seems quite satisfactory) and shopped. Alas, that shopping! The MairieEpicerie is not much good, Moench on the opposite side lower down is better. For a charge of 100 francs a motor took us 16 miles over a col and up a remarkable ravine, Scala di Sancta Regina, to the village of Calacuccia, along a marvellous winding road with scores of sharp corners and several hairpin bends. Brown is a bold and confident driver, but in the front seat next the Frenchman the pace round the corners put the wind up even him. In the ravine the rocks were eroded in a singular fashion, but we were reminded of the Highlands without the peat rather than of the Alps, and the rain and low clouds of the afternoon fell in with the impression. Renwick in his RomanticCorsica considers this the most beautiful part of the island.

At Calacuccia we put up at the Hotel de France, a small clean inn (with a shop) having all the comfort one can expect, but according to its advertisements a “ first-class hotel with modern comfort.” We went to bed happier, because the clouds broke, and wiser, for we had discovered the troubles we anticipated were non-existent. Corsica is simply an ordinary country. The roads are good, useful roads, and motors can be obtained everywhere at cheap rates, 6d. a mile. There is no “ back of beyond,” some of it caters for holiday people, most does not. You can buy anything in the shops the natives buy, and the things the natives don’t buy, you do without, exactly as in London or the West Riding. The journey to camp was no more difficult or out of the local routine than to a camp in Lakeland, but our food supplies were not so satisfactory.

Bread and butter were excellent ; after ten days the Corte bread was still soft, though the Calacuccia bread was getting hard, but the bully-beef and Heinz beans sort of thing was unprocurable. A bit of ham was good, a curious sort of cold pork in a cloth I could eat, but Brown could not. Jam and sardines were as usual, but we could get no tinned fruit. We went to camp firmly believing that we had secured seven large tins, but to our horror they had inside a tasteless jam made of every possible kind of pulp, which even I had great difficulty in getting used to. Then, too, at that season of the year there is only imported fruit in Corsica, principally bananas, but at Corte on Saturday afternoon the whole week’s supply had gone. But heaven be praised for onions, which, eaten raw, contain in a little a whole alphabet of vitamins.

Sunday, 12th May, leaving our suit-cases and unnecessary kit, we set off under an overcast sky with a badly loaded mule, did two miles on the road to Albertacce, followed a stony track up the Val de Viro by chestnut orchards to Calasima, which we passed under a hot sun in two hours, and in another 1½ hours over a very rough path reached the big boulders called Grotte des Anges. On the only level and stoneless spot, a patch of gravel covered with thin grass, the tent went up as it usually does, in the rain, and the muleteer left us to apparent loneliness, He charged 50 francs, but insisted on more for the return journey!

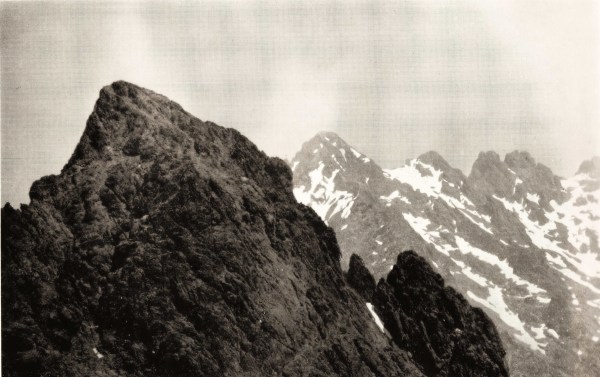

The situation was magnificent. The left bank, that of the Cinque Fratri,was bare all the way down from just above the Grotte des Anges,but the opposite bank and the whole Val de Viro above was covered by forest of Corsican pines (PinusLaricio) .Castelluccia was opposite to us, further right the glorious Paglia Orba, then Tighietto, Uccello, Minuta, and Capo Larghia far up the valley. On our own side we had the Cinque Fratri behind us and could see almost to the top of Monte Falo. There was no turf, but endless stones, and compared with the Alps, few flowers–they simply cannot survive the dry summer. Great masses of hellebore were much the most conspicuous, and crocuses abundant.

Monday’s expedition was an ascent of 3,000 ft. up the broad ridge to Punta Castelluccia direct. It was very hot in the forest, and by the time we reached the limit of the trees we realised that heat is one of the impediments of Corsican climbing and that we were in for a struggle. Presently on the easy rocky ground we struck maquis, here brushwood growing downhill, used a snow slope, an awful grind, to avoid it, and at last reached the final rocks covered only with juniper and some crocuses. In spite of a seven a.m. start we only covered 3,000 ft., the height of Scawfell, in five hours in a very exhausted condition.

The breeze was refreshing, in fact our two hours on top became uncomfortable owing to cloud and cool wind. There was no distant view, the southern mountains being in dense cloud and the Viro group mostly so. The descent was down easy snow and we began to acquire knowledge of what maquis through the snow means, solid ground and not a rotten bridge over a big stream. When we reached camp the sun had gone and it was too cold for a bathe.

On Tuesday we decided just to scramble up on to one of the Cinque Fratri, 2,000 ft. above, and enjoy the view. So we started this time at 5.30 a.m. and went first down the valley, and ascended happily for a time. But the instant the sun struck us we collapsed and it was as much as we could do to struggle up the first Brother after four hours. We visited the second, but the heat drove us off at twelve, and we walked down the easy side of the Brothers and stumbled down the stones to a tributary beck at two. We were determined to bathe, but the sun instantly disappeared. This is a game which can be played with great success in Britain, but it does not go in Corsica, so we sat it out and after three quarters of an hour all the available supply of clouds was used up and we got our bathe.

A shepherd arrived and we held such converse as we could about many things. At one time he appeared to be telling us of the presence of woodcutters in the valley. On reaching camp we continued the experiments already begun on trout-fishing and digging for worms. Brown had provided a trout rod and a minimum of experience, my contribution was some emphatic Gritstone advice on the only place to dig. We were greatly cheered when Brown caught three fish, which went to the good against the fact that the coffee had not been ground and had to be hammered between stones, and the annoying disappearance of his watch.

It was a cold night followed by a glorious day with a very cool breeze. We bathed, caught four more trout, and slept peacefully in sunny recesses in spite of the prickly Corsican plants. In the afternoon we wandered up dale through the wood, found wood piles, then a hut, and finally eight Italians sawing planks by hand. So accurate was their work that we had supposed a machine saw to have been used. The Italians are wonderful workers–one wonders how all the stupid attacks by pro-Germans can persist.

Our walk resulted in the discovery of a faint track from above the Grotte up to a little colwhence the Falo and Albano becks could easily be reached. But our day’s observations also entirely removed the impression of loneliness. The camp and all our movements were under constant observation. Every morning a donkey or so went up and down from the woodcutters, and I frequently heard some one come past the tent in the early hours. Later came the shepherds,bergers, from Calasima, driving two or three hundred miserable sheep up and round the valley wherever thin grass was to be found. A week later they constructed a bridge opposite the Grotte des Anges. The bergers were always ready to chat and very curious about our equipment.

Our suspicions now being roused, we turned everything out of the tent, went through all our property and the powdery bracken which was the only thing we could find to put under the groundsheet, and were driven to the conclusion that the watch, left hanging inside the tent, had been stolen on Tuesday. Hitherto the Corsicans have borne a reputation for scrupulous honesty, but though our suspicions first fell on the Italians, there was later some ground for thinking the thief was a native.

Heavy rain fell all night. At five and at eight dense clouds and rain forbade a start for Paglia Orba, but soon after nine the weather set fair. A very hot walk of two hours took us to Calacuccia for lunch. We interviewed the gendarmes, and the chief, though quite hopeless of recovering the watch, promised that a detachment would visit us next day at three.

We got away well before 4 a.m. on Friday, crossed the little col and followed a natural line through the forest on the left bank of the beautiful Falo beck. There was a most refreshing breeze, and above the trees we made splendid progress, keeping below the masses of maquisand closing in on the stream until we reached good hard snow. I am unable to discover in any book which bush constitutes this high growing maquis. It was not in leaf, recalled alder, and it has been suggested it was a dwarf beech. Altogether maquis includes a dozen different plants, but only two grew near our camp.

After breakfast it began to occur to us that the delightful breeze was remarkably cold, and against it we were equipped with one thin cardigan and one pair gloves. Clouds were everywhere, there was no sun, but the group generally clear and the distance not so hazy as hitherto. We passed over Monte Falo at 8.20. The snow on the west was brick hard, there was ice in places and a troublesome wind. Instead of the direct ridge to the Col de Crocetta, the head of the Val de Viro, we used the rib to the left and had to double rope once, reaching the little peak beyond the col in an hour. The next bit of troublesome ridge we dodged by easy snow and stones on the right, then over stony slopes we gained a summit where commences a broken ridge reaching to Monte Cinto. Along this we went as hard as we could, in view of our engagement with the gendarmes, and I believe we reached the foot of the final re-ascent to Monte Cinto.

The wind had so far been very trying, but once we turned the sun appeared and we had a short and pleasant halt on the Col de Crocetta till noon. The snow was soft and treacherous, most dangerous we found at the top of each slope, but good glissades carried us a long way down. Then over awful ground, where we saw two moufflon, we at length came opposite the Bergerie de Ballone, but failed to find any path. Patient stepping over terrible stones brought us to camp soon after two.

Three gendarmes, armed, had been there since eleven, had interviewed the Italians, had caught many trout with Brown’s rod, in fact had had quite a pleasant excursion, but had of course not been able to do anything for us.

Saturday was a glorious day, spent in idling. Trout fishing was pursued with increasing success, and perfect division of labour, I who refused to thread worms on hooks, doing all the gutting and Brown getting the sport. We saw no one.

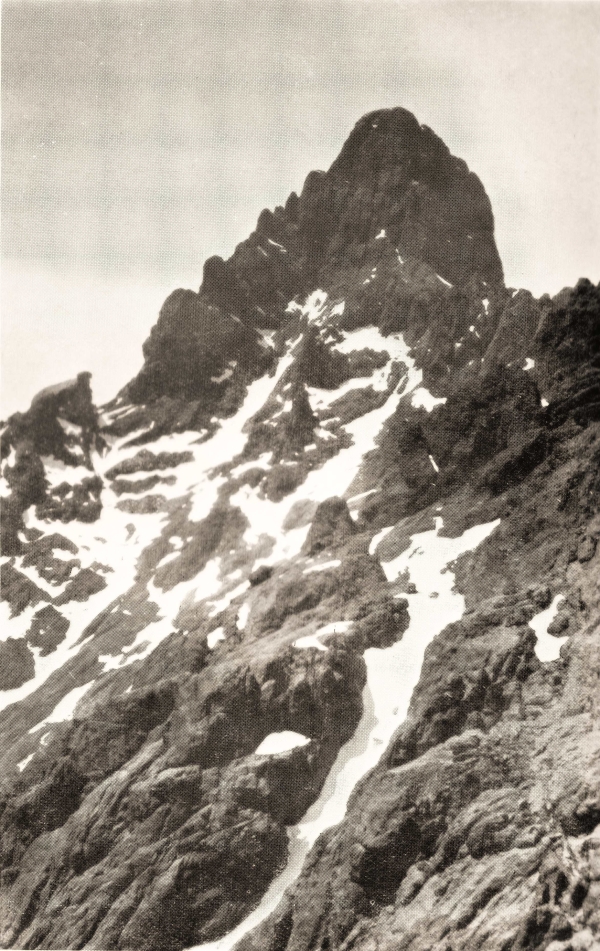

The 19th was our most successful day. Provided with warm clothing this time we went up to the Col de Foggiale, most of the way on snow in a great gorge and gully. 4.50-7.10 a.m. We were greeted by a bitterly cold gale and had a most uncomfortable meal. Then on scree we rounded Paglia Orba slowly ascending, and on very hard snow passed just under the Col de Tafonato. We had had to be vaccinated before coming out to France, and the climb on to the rocks of Capo Tafonato was quite stiff enough to remind Brown that his had been unpleasantly successful. Thence by a snow patch, an obvious ledge to the left to a leaning boulder, a short climb up either to an easy or a harder ledge, the route leads to the famous hole through the mountain. The view is magnificent, but the position is not quite so sensational as is sometimes suggested. We were extremely interested to see a road coming over a high pass and descending into the valley below. The W. side of Tafonato should therefore not be entirely inaccessible. An extraordinary rake leads across to above the Col de Tafonato and an easy ascending line round the corner to a difficult slab below the summit. This Brown conquered neatly and out of the bitter wind in glorious sun we spent the hour from nine to ten. The descent by an easier but longer chimney avoided the slab.

About noon we left the snow patch on Tafonato and attacked Paglia Orba, which looked formidable. The rocks were wonderful, and some extraordinary places were conquered without difficulty. We hit the foot of a great slab half-way, bore left into a wide gully or small snowfield, had to rope because of the exit to the left not going, came out over easy rocks to the right anywhere and in spite of the top being a long way behind reached it at two. I should like to mention that Robinson and Smith (Gritstone Club) returned from Capo Tafonato by passing under the great North Face of Paglia Orba.

Under a perfectly clear sky, for once we saw a coast view to the S.W., and more mountains to the south than ever before. To the Col de Foggiale took an hour, the only awkward step being the passing of a line of crags by a snow gully where we had to kick and cut in good snow two hundred feet. With the help of glissades and increased familiarity with the less rough parts of this valley we were back in 1½ hours. The exceptional extremes of the glorious day were followed by a cold night, and a continuing cool wind. Monday afternoon was so overcast that the bergers took the sheep home early and the trout would not bite, but no storm came on.

We were just off to bed when Robinson and Smith burst upon us, three days out via Bastia (5 a.m.) but at the cost of 100 francs for the evening trip per mule. Besides their company they brought all the luxuries we lacked, oranges, etc., and such uncanny skill as fishermen that it is no wonder the bergers complain there are hardly any trout nowadays.

On the 21st Brown and I left for Punta Minuta at 4.45, after the warmest night so far. We held the so-called path to the Bergerie de Ballone, crossed, and by easy rocks and snow slopes gained the upper Col di Minuta at 7. 30. It was obvious to us that the Uccello-Tighietto traverse should include another peak nearer Minuta, and that it is one of the best things in the district, but we had missed it.

In 1¾ hours we climbed Minuta, avoiding a great green tower on its right. About ten, thick mist swept round us before we had formed any clear idea of the peaks ahead. Descending the E. ridge we had to halt for some time to make sure which of twin ribs ran to the col. We went straight at Capo Larghia I. and seemed to get up very quickly (noon). Large painted letters showed clearly that there had been other visitors.

The only glimpse we caught of Capo Larghia II. did not suggest that we should have difficulty with it. However the mist remained so persistent, we hesitated before tackling the chimney straight ahead, but finally descended it, a sporting climb, and slabs to a col which was not, I think, the lowest between C. Larghia I. and II., and thence to snow. Once on the main snowfield we went down fast. Past the place of the moufflon we picked our way steadily in heavy rain to the Ballone “ path.” The storm did not quite fill the day, which closed round a huge log fire and a tremendous feast of trout.

We now decided to give up camp and make an excursion to Asco, a much talked of village, “ the most beautiful in Europe,” on the N. side of the group. I went down to Calacuccia on Wednesday and had to beat down the muleteer to 70 francs before he would come up for the baggage. On the Thursday morning, a day of extraordinary extremes after a fearfully cold night, I climbed in three hours to the featureless skyline to the south. It was most interesting to find that the highest patches of wood were beech, the old Corsican forest, growing almost up to 5,250 ft. level. The mountains to the north were clouded, and I gained no information. Those to the south cleared a little after a fierce thunderstorm at noon, and left an impression of a Scotch rather than Alpine character. The Tavignano gorge between us seems to be extremely fine. Following a broad ridge a mile over gravel and grass, I descended by a very rough mule path from the Col de Rinella.

Brown had come down with the caravan and we spent the evening at hard mental work, finding a route to Asco over an intricate country from the old black and green French Ordnance map without contours. This is out of print, but Wade had very kindly lent us his copies, now of considerable value, as there is no other map of Corsica other than the cycling variety, and we were relieved to return them undamaged. The trouble was the absence of indication as to whether the three gorges to be passed on the long route to the pass required serious descents and ascents, and the ignorance of the natives as to whether it could be done.

We left on Friday at 6.30, went two miles down the road to a big bridge, then by mule paths by Corscia to Costa and in great heat a good 500 feet down to cross the Radda. We felt the day was lost, but the move up developed into a mule path of obvious importance and continuity, if not much used, leading us for hours over rough and steep ground high above the Radda, turning over a ridge, high above a second gorge and up through its forest to a critical position on a little col whence we viewed the Ancino. Our luck was in, the gorge was below us and an almost level traverse landed us in the upper regions which reminded us of the head of a Highland glen. At this point we finally lost the amusing company of a man, a boy, a donkey, and three pigs who had been within hail since the Radda. The flora had been more copious and varied than hitherto, while some erosion forms were rather staggering. I admit that the hollow boulder with a door and window may have been trimmed up, but smaller hollow boulders were certainly not artificial.

Avoiding the maquis we took the west branch of the Ancino past the Bergerie de Galghello to the Pass, where we arrived with joy at 12.20. The contrast of the truly Alpine character and steepness of the northern side was surprising, though there was only one strip of snow. Clouds prevented a full view of the end of the Cinto range, and presently the noon thunderstorm swooped upon us, and greatly refreshed us.

On the long steep 3,000 ft. descent we luckily bore left to the Bergerie de Pinnera and avoided difficulties. Down through the pines with great fat cones (PinusPineaor Stone Pine), and at the end of 1¼ hours the sunshine had come again, and we were ready for a glorious bathe. It made us very slack and when we arrived at Asco Bridge at five, we looked very sadly at the 400 feet of ascent and wondered gloomily where we should that night lay our heads, for Calacuccia openly said there was nothing at Asco. By great good luck, the first group of men addressed put forward the patron of the Hotel de Cinto and having convinced him in emphatic terms that we were not Germans, in two minutes we were sitting in a comfortable simple room.

Later we ate a splendid dinner and had the best breakfast in Corsica, that is with jam and butter instead of bread only, bill 70 frs. Asco may be the most beautiful village in Europe, but the singularity of its access is now ruined by the trace of what is to be a road, and there is no forest, no shade, no place for a bivouac in the two hours long valley. At length we emerged and held on for miles along a road over unenclosed heath in terrific heat, then we saw a man cutting hay, the road to Calvi, and came in four hours to the railway station at Ponte Leccia, horse-chestnuts and roses, and a much needed bathe.

On the way back to Calacuccia by rail and bus we came across a local party and a German party both bound for the Grotte des Anges, which seems to have become a crowded neighbourhood.

On the following day we went to Bastia, where we do not recommend the bathing. We further entirely contradict Renwick’s RomanticCorsica on the serious question of afternoon tea. Except at the hotel of many names, the Palace, it cannot be obtained in Bastia. The voyage to Marseilles with a night on board was very comfortable, but the landing, due to Corsica being outside the French customs, is a terrible affair, and is probably a less serious business at Nice. Otherwise by spending an afternoon in Lyons and the night in the train to Paris, we made the journey work out comfortably.

A thunderstorm in Lyons was accompanied by a long continued fall ol hail of the kind one hears of with scepticism. Lumps of ice as big as eggs we saw with our own eyes, traffic was stopped, twigs torn off the trees and a great deal of damage must have been done.

Minor misadventures followed us to the end. We did get our property in time, but the trout-rod was left in Bastia, and the van containing our registered luggage was derailed in Kent, without involving the rest of the train, and left behind.

If the mountains of Corsica have not the tang of the Alps the rocks are good, and there is much snow in May. In summer they must be a waterless desert, and climbing impossible. The May visitor will never regret the long journey.

HEIGHTS.

Calacuccia .. 2,780 ft. | Grotte des Anges .. 4,300 ft.

Paglia Orba .. 8,278 ft. | Monte Cinto .. 9,121 ft.

Capo Tafonato .. 7,687 ft. | Monte Falo .. 8,364 ft.

Punta Minuta .. 8,501 ft. | Capo Larghia .. 8,268 ft.