Goyden Pot, Nidderdale

The Club Meet at Middlesmoor, on 8th and 9th October, 1921, led to the invasion, by at least 15 people, of the labyrinth discovered by Barstow and Stobart in 1912.

The interest aroused in this now very remarkable cave decided the Editor to publish the plan of the labyrinth, and a description of the cave. The original explorers have, however, shown no literary enthusiasm and he has been left to do the text himself.

The completest description so far is G. T. Lowe’s. in Bogg’s Eden Vale to the Plains of York, which takes one as far as the end of the River Passage and describes the cave as containing much mud. The mud has now gone and the climb along the rapid descent of the river is easier, no rope being needed. The Editor understood that the cave is regularly flushed by the discharge of masses of compensation water from the Angram reservoirs higher up the Nidd, and that it is by no means a place to venture into without careful enquiry. To these floods is probably to be ascribed the removal of the mud spoken of in earlier descriptions.

A citizen of Bradford having interviewed the Lord Mayor, and the Lord Mayor having ordered restraint of the waters, the Club is duly grateful for the safety and pleasure of their day below, in the otherwise dangerous area.

First, let us destroy the fable that Goyden Pot is only a mile from Middlesmoor.

Next, let it be understood that Goyden Pot is the big cavemouth, into which in wet wintry weather the whole River Nidd rages. In drier times, when the river disappears higher up, it is to be seen in Manchester Hole, a cave 20 yards from the bank, on its way to Goyden Pot.

At such times one travels into Goyden along a dry wide passage to the first turning on the right, and a short distance it along this into the River Chamber, down the side of which one scrambles to where the Manchester Hole water, i.e., the Nidd, emerges.

To complete the exploration of the upper level, a few steps forward from the turn to the River Chamber there are two openings on the left which are simply the ends of a big ox-bow. Opposite them is the big window looking down into the River Chamber. Further on the main passage bends left, and finishes in a chamber which, in October, 1921, had three plugged exits. Seaman states that these were once clear and led to other chambers.

In the River Chamber, the Nidd descends rapidly and then flows along a fine stream cave. This is gained by a fairly difficult scramble down big clean rocks, finishing by a tricky little traverse above a pool. On the way the roof descends, and forms a bridge with wide upper passage. Seaman reports 30 yards of it plus other passages.

On the River, after a sharp turn, wading is necessary, and it cannot be followed further than a wide bedding plane, partly choked with timber, in which the water seems to meet the roof.

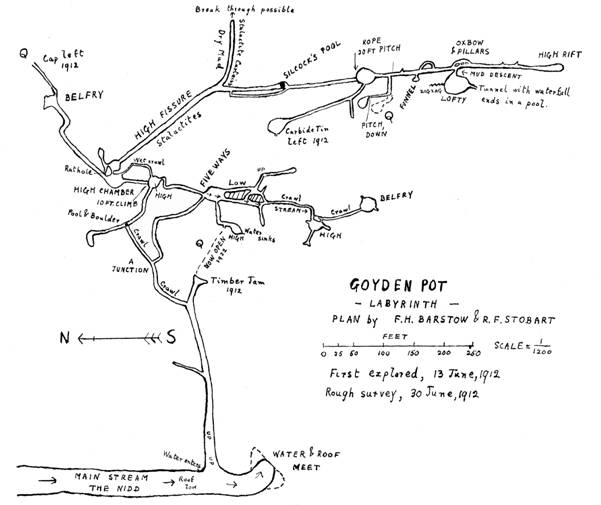

On the left, a little before the end, is very obvious the mouth of the Labyrinth, and, not so obvious, the inflow of a tributary. So far we have walked upright, the rest must be assumed to be crawling, unless the context shows otherwise. Barstow and Stobart first explored the new passages 13th June, 1912, and made a rough survey on 30th June, 1912. Their plan was found by the 1922 parties to be a remarkably accurate piece of work, though only done by pacing and compass, especially for the time taken, said to be four hours. It is reproduced with some verbal additions only, and two points have been marked Q where additions may be made and one where it is doubtful. A future expedition should aim at checking these points and at putting in the exact course of the little stream in the most intricate part near the Five Ways.

It would have been interesting to know whether the first explorers found the entrance as clean as did the 1922 parties. At the first fork, Burrow’s party went straight on and came to the Five Ways. Hence the Timber Jam of 1912 must have gone.

The Editor’s party crawled past the “A” Junction, the pool with boulder, to the Ten-Foot Climb, which is the best landmark in the labyrinth. Once up this comes some walking. “The Cap Tunnel” from the Belfry, marked Q, has been followed many painful yards without reaching the end. It has not been paced.

The next portion, a high fissure, feels like a broad highway. It contains some fine stalactites etc. and a singular beehive mass. Like other “beehives,” this beautiful formation appears to be solid, but proves instead to be a mere shell, and actual beehive shape. It has clearly been formed over mud, which is now being washed away. There are several signs that changes are taking place in the mud deposits here, and the place deserves a careful examination.

Beyond the pot-hole with the 20-feet descent, where a rope may be left, the furthest reaches of the cave are most interesting and well worth the crawling to visit. The extreme end and the side pot-hole are both very lofty and very fine. It looks possible to climb a long way up the curious funnel or chimney opening on the west of the passage. Almost every characteristic of water action on limestone can be studied in this area.

Six and a half hours were spent underground.

The question ever present in the minds of all who enter the Goyden Pot Labyrinth is, to what extent is the place flooded during the discharge of compensation water?

The Editor’s opinion, given for what it is worth, is that last October, the low clean passages extending from the Ten-Foot Climb and the Five Ways to the Nidd had been filled very recently, and the high passage with stalactites had been invaded. Beyond there were no signs of flooding, and in fact there was a passage with dry mud to crawl over, a much appreciated change.

E. E. R.