Cave Exploring In County Clare[1]

By E. A. Baker and H. E. Kentish.

The Cave Of The Wild Horses. – It was our landlord at Gort who first told us about the cave, but the wild horses we did not hear of till later. Wherever you go round Gort you come across caves, devil’s punch-bowls, underground river-beds, huge cavities engulfing water, and underground channels now deserted by their streams and brilliant with calcite and stalactite. There is also Lough Coole, a quiet lake that receives the worst-behaved of all these streams, yet never gets any fuller, though it has no visible outlet – a mystery explained, though not to the satisfaction of the peasant mind, by the existence of a large submarine spring a few miles off at the head of Galway Bay. In Clare and Galway, in truth, there is more water running below the surface than one ever sees above it. But the attractions just enumerated were of trifling interest compared with the landlord’s secret – the name and whereabouts of a cave that had not yet got into any guide-book, that science had not explored, and the natives were afraid to enter. Not till we got him into the car and found ourselves going west did we realize that this was not in County Galway at all, but somewhere over yonder in Clare, the limestone border-line of which towered far along the horizon. The amount of refreshment stored away behind indicated that it was some distance off.

Yesterday we had come down from this limestone frontier, through the biggest thunderstorm Ireland had had, so they told us, for thirty years; and to appreciate a thunderstorm, I venture to say, no sea-cliff, no mountain peak, provides such appropriate scenic accessories as this debatable land between Galway and Clare. lt is the margin of that hopeless region, the Burren, into which they used to drive evicted Catholics in the old days, and which was described as not having enough water to drown a man, trees enough to hang a man, or earth enough to bury him. Yet there are hills and valleys in the Burren, refreshing copse, cheerful heather, and a flora as choice as in any limestone district. But this Galway side of it, beyond a doubt, is the stoniest waste in the British lsles. Right, left, in front, as far as we could see, stretched a pavement of naked limestone, the polished slabs they call “clints” in Yorkshire here displayed on an unparalleled scale. The land, if “land” is the word for it, is let at three-halfpence an acre, and the poor beasts have a hard job to get his money’s worth for the farmer from the few inches of browsing that come up through the cracks. From north to south of this landscape an inky sky spread, dazzling flashes lit a prospect as infernal as unassisted nature could produce, rain-torrents splashed us right underneath the hood, and we wondered whether India rubber tyres were really as safe an insulator as people state. To-day, the weather was of that moderate degree of softness which they regard as fair in Ireland, but the clints did not look much more alluring. The terraces of the higher Burren, with the wonderful campanulas and cranes’-bills by the roadside, were a great relief, though we had to walk some of the hills. Altogether, in some fifteen miles, we passed barely half-a-dozen cottages. Then we came to a cluster, one of them a decent farmhouse, and our guide told us to alight.

We thought, of course, that we had reached the cave; but an Irishman cannot appreciate the disinterested motives of the speleologist, and accordingly our landlord had brought us to what he thought a more profitable subject for investigation – a mine. lt was an abandoned mine, yet doubtless there were still possibilities in it for the expert. All we found, however, was mud, and we were glad when a patch of deep water gave us an excuse for declining to explore any farther, and insisting on being taken to the genuine cave, about whose existence we were beginning to have doubts. Another half-hour of dodging along byroads with numerous hairpin bends and gates that had to be unfastened in the pouring rain, brought us to another farmhouse at the head of a little valley exactly like those you find nestling under limestone crags in Craven or the Peak of Derbyshire. One feature gave the characteristic difference, and that was the ruined shell of a church standing in its graveyard beside the road. Kilcorney Glebe is the name of the spot, and right opposite, beyond what the Ordnance map describes as a “turlough liable to floods,” was our cave, at the base of a handsome limestone cliff. The spot is about a mile south of Carran, and six north-east of Lisdoonvarna.

We learned a good deal whilst we were getting into our overalls at the house. Out of this cave of Kilcorney, in days of old, a herd of wild horses had issued and ravaged the plains of Ireland. Perhaps they were ancestors of the famous horses of Emain. There were variants of the legend, we afterwards found, and many persons aver that a savage race of horses still make their den in the bowels of Kilcorney. More to the point was the information that water never runs into the cave, but that in rainy seasons a flood pours out with a noise that is heard for miles. The cave runs in at the foot of the cliff in a downward direction, but, with no stream-course to feed it. On the contrary, the “turlough liable to floods” is obviously watered by streams forced up from below. Our cave, in short, is a kind of safety-valve or overflow-pipe, which comes into action when the cavities of the hills are glutted, discharging the excess of water that cannot be carried away fast enough by the subterranean channels.

It was rather disappointing to find, after all, that we were by no means the first in the cave. The entrance tunnel was full of traces of humanity, which grew scarcer, however, as we proceeded, though beyond the first severe obstacle – a passage blocked by enormous stones, with a tight and cornery descent at the other end – we still found some evidence of former visitants. One of our party, a recent convalescent not eager for toil and hard knocks, turned his attention to a subsidiary passage. The landlord’s enthusiasm had lasted only as far as the cave mouth. We speedily found something that would be a sore tax on the two of us left. At the end of painful crawl we suddenly found ourselves on the rim of a great funnel, plastered with slippery mud, a black, gaping hole at the bottom leading to unknown depths. Previous explorers, we soon ascertained from inscriptions on the walls, had reached this point and the end of a by-passage and then retired, daunted by the aspect of the funnel and the hole. Doubtless, we were near the birthplace of the legendary steeds.

It is a strict maxim in caving that one man must never let another down a vertical drop single-handed, because it is impossible to get him up again by a direct pull. Stones thrown down indicated some fifty feet. For a bit we were in despair, then we remembered our pulley. We had picked it up a few days before, in a moment of inspiration, at a marine store in Dingle, thinking it might be useful some day. It took half an hour to fetch it from the car. As the lighter man, I tied the pulley on in front. Kentish attached our A.C. rope to a jammed block above the hole; the rope was then threaded through the pulley, and I prepared to descend. Even if it came to a vertical pull up, Kentish would have only half my weight to support, the other half depending on the fixed rope.

All went smoothly – too smoothly, for the walls of the chasm were not only unbroken by a single ledge, but coated with a lubricating sheet of mud. Then the rocks were cut away, and I found myself sliding down the corner of a mighty cube of limestone, without a hold to save me from swinging to and fro. Below was darkness, composed chiefly of black mud. Then at forty-five feet down I stepped off on to a peak of mud, and grasping the rope-end essayed to reach the base without slipping helplessly into the unexplored. There were lofty passages going in several directions, one of which I easily followed for some distance. But there were other openings that could not be entered without assistance, and it seemed best to return for the present to see if Kentish could possibly join me with more help. The pulley trick worked admirably. Kentish got me up, but as no one could be induced to lend a hand for further exploration we had to be content for the present with the discovery that Kilcorney has a lower series, apparently much more important than the series previously known.

Our second chapter opened a year later, in 1913, when we induced two gentlemen, hitherto innocent of any wish to explore caves, or of any misdemeanour deserving this particular form of expiation, to lend us their muscular assistance in a joint descent of the mud-funnel and the hole. With several ropes to carry, we found the long crawl more excruciating than ever, especially as the tunnel had water in it, and there was no keeping dry except by straddling across with one’s back forced against the roof. Piteous ejaculations came from the disillusioned volunteers, their moans changing only a semi-tone or so when they beheld the horrors of the funnel and the pit. Nevertheless, one of the novices followed down for the first trip, Kentish coming third.

We did not reach the wild horses. A main passage running at right angles to the chief passage overhead gave access eventually, by a cross road, to a parallel cave of no little beauty. Over a floor paved with ridgy stalagmite a brook came purling – the first brook we had seen in the Burren – spreading into a pool, whence it ran with a strong current into a fissure too narrow for us to penetrate. Close by this pool, separated from it by a mere lip of stalagmite, a pot-hole, thickly encrusted with stalagmite, ran down ten feet into a side fissure, and though the water was brimming up against the lip none ran over, and the fissure was practically dry. Other passages led into huge, misshapen, mud-lined chambers, with mud-lined pot-holes in the floor. There were also transverse openings and chimneys, but none led us far. At one of the cross-roads a startling incident occurred. Some five feet above the ground a big block bridged the passage, and to reach a point above it I scrambled on to this and into the chimney beyond. In returning, as I rested comfortably on the block, I felt a move, and next moment it was on the floor with a terrific bang, sending my lamp flying and throwing me across the cave. Well over a ton in weight, the stone had been balanced on two points no bigger than a finger-nail; it left only two minute scratches on the walls. Luckily it fell too far out to block up the passage through which we had to return. We had all crawled underneath several times, thinking it was a solid roof above us.

To the right of a man descending the big limestone cube under the funnel, one looks down a steep mud-slope to a pot-hole choked with mud, above which a branch passage ascends at a forbidding angle. Kentish climbed up this for twenty feet, and found the return ticklish. The main passage goes on to the left, but at right angles a narrow fissure passes behind the rock to a widish chamber containing another mud-lined pot-hole, which we could not descend for lack of a spare rope. As it appeared quite shallow, and the mud was some feet thick, there was no encouragement to explore it further.

Having gone along every branch, and definitely ascertained that Kilcorney Cave does not communicate with Galway Bay, or with the fabled home of the wild horses, we took our turns at the painful ascent to the mud-funnel, accepted each our share of the disparaging remarks from the friend who had spent some hours in the mud, with a solitary candle, waiting for us at the pulley, and returned to the “turlough liable to floods.” At Lisdoonvarna they were sceptical when we said the wild horses were a myth, and told us of a cave, quite in the neighbourhood, where a sea-beast comes out and roars at stated intervals. This sounds more exciting even than Kilcorney, and we hope to explore that cave shortly.

E.A.B.

Other Caves. – Near the supposed lurking place of the wild horses, but higher up in the cliff, is a large archway conspicuous from the road. This cave runs into the hill for about twenty yards, and then becomes silted up. It was probably inhabited in prehistoric times. Layzell began digging here, but in the short time available was unable to do very much. It appears very promising. This cave seems to have originally connected up with two other caves, visible from its mouth on the other side of the valley, before the latter was farmed. We explored these caves, and also various small rifts in the sides of the hills, but could not get in very far.

About two miles from here, on the road to Lisdoonvarna (on the cross road to Ballyvaughan from Kilfinora), we noticed a series of swallets. The first was choked, and would need to be dug out, but appears to be worth the trouble. We were on the point of leaving when we found a small cave hidden round a corner of rock. It was about seven feet high and two feet wide, and we followed it in nearly horizontally for about 680 feet. A short distance in, a stream fell from the roof and ran along the passage to its end, disappearing into a pot. This pot was in the side of the main passage, the entrance a very narrow and twisting crack; and although I got into the top and could have descended, it appeared unlikely that I should be able to get out again without a ladder, so I came back. The pot appeared to be about twenty-five feet deep, with smooth, round sides, and there did not appear to be a large outlet at the bottom. On the far side of this, and in continuation of the passage we had entered by, another passage came in. It was very cramped, and the floor covered with mud, iced over with an elusive stalagmite crust, which gave way under us as soon as we were fairly on it. Baker went in first, uttering awful groans, and found a pretty little stalactite chamber. I followed him, and went on to the commencement of this passage – a stalagmite fall from the roof. To get there I had literally to swim through three feet or more of mud, and presented a magnificent spectacle upon arriving at the entrance again. This cave, which is called Poulwillin, appears not to have been explored before.

Meanwhile, the hotel people having discovered our soft spot – I am sure they thought we were all mad – reports came in daily of fresh caves in the neighbourhood. Truly this region is honeycombed with caves. There were caves near Ennis, caves between us and the coast, and more caves on the slopes of Slieve Elva, towards Ballyvaughan. One of these latter, near the farm of Caherbullog, was said to have been penetrated for two miles and a half. We received this information rather sceptically at first, but afterwards had every reason to believe it true. We decided to complete our programme for County Clare with an examination of this cave, leaving the others for a future occasion.

It is situated close to the road skirting the eastern side of Slieve Elva, about six miles from Lisdoonvarna. There is a big funnel-shaped hole, with perpendicular walls on two sides, about sixty feet deep and a hundred in diameter, overgrown with trees, and below it a large perpendicular shaft about forty feet deep. A small quantity of water runs into this pot-hole and disappears into a horizontal tunnel at the bottom. There is also a big rift running into the side of the hill above the pot-hole, which can be entered through a small hole in the grassy slope near the surface. I let Baker down into this rift, but could not follow him, as we were by ourselves on this occasion. He was unable to explore this rift very far, as it proved to contain a staircase of deep pools held up in stalagmite basins, extremely beautiful, but difficult to traverse without planks or ladders. Our chief object, of course, was to explore the cavity below, and we wasted very little time here.

We next turned our attention to the tunnel leading from the pot-hole. Somewhat like an oval drain-pipe, its walls had a surface like hammered metal, the little stream from the entrance forming in places deep pools. We twisted and turned in a most extraordinary fashion, and once or twice had to take disused upper passages to avoid deep water at our feet. The passage gradually enlarged, and at times became an enormous rift, stretching for a hundred feet or more into the roof, and expanding into a chamber below, round which the stream had cut out its channel. At 513 yards from the entrance a large waterfall came in from the roof, no doubt from a pot-hole on the opposite (east) side of the road, which we had examined but been unable to penetrate. A wide chamber with a capacious floor ten feet above the water occurred at a distance of 1,400 yards from the cave mouth, and here we found the names of several early visitors inscribed. Then came a huge dam of enormous boulders, and in various spots very magnificent cascades of stalagmite, which looked most imposing against the prevailing blackness and bareness of the cavern. At 1,563yards we met a tributary stream coming down a huge cavern exactly like the one we were following, but we only ascended it a short distance, returning to the main stream. At about 1,800 yards from the entrance we decided to turn back, as time and carbide were getting short – we had not come prepared for such a cave as this. If our information is correct, the cave extends a mile and a half further, and finally ends in a sink.

On our return our driver, J. Connolly, who by his local knowledge was quite invaluable to us, told us of another pot about a mile nearer home on the east side of the road, which, he said, was so deep that a stone dropped from the surface would take a quarter of an hour to reach the bottom! This would make the depth about thirteen million feet, so we got quite excited!! This was so overgrown with trees that we could not see the actual hole. A rock thrown down appeared to strike some kind of bottom at about a hundred feet. Unfortunately we had to leave this also, as we were due at Enniskillen to meet Wingfield in twenty-four hours. Its name is Poulelva.

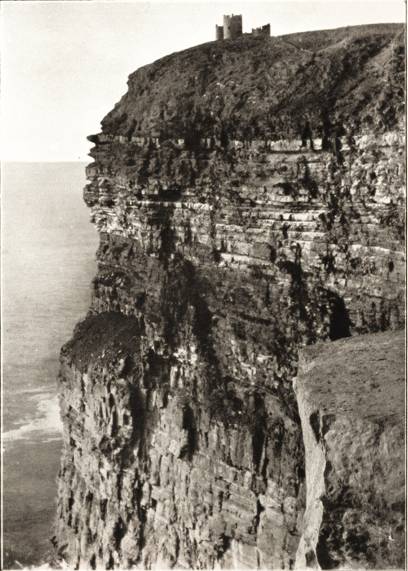

While staying at Lisdoonvarna we made an expedition to the cliffs of Moher, which face the sea about three miles to the west. The strata here are nearly horizontal, and the cliffs have a perpendicular height of over 600 feet. The rock is millstone grit. The walk from Doolin village along the edge of the cliffs, which gradually get higher and higher till they culminate at O’Brien’s Tower, is worth going far for. It should be continued past the Hag’s Head to Liscannor. Before leaving Lisdoonvarna we visited the sulphur springs. We had hitherto thought the Harrogate water sufficiently unpleasant to effect any cure but that of Lisdoonvarna is just five times as powerful. Its taste is best left to the imagination.

[1] Acknowledgments and thanks are due to the Editor of The Field for to use much of the following material, which appeared in his columns.