The Siege Of Mere Gill

By E. E. Roberts.

Wanderers on the northern slopes of Ingleborough seldom fail to pass by the long and curious rift into which Mere Gill Beck falls. At flood times the roar is tremendous and it is a wonderful sight, standing on the great rock bridge, to watch the huge waterfall pouring into the pool 40 ft. below and the smaller fall close by, leaping out and dashing against the rock-pinnacle which rises from the depths. The remainder of the rift is only a few feet broad, and has for floor the same pool, which is usually some 50 ft. deep, but in very dry weather shews a little beach under the fall and a steep slope of mud running down under the bridge into the shrunken pool. From this slope you can look right through the narrow rift to the northern end, where an underground stream tumbles in. Fluorescein has shown that this stream is the same as the odd little beck labelled P. 101, which can be seen breaking out from the flank of Ingleborough some distance to the S.W.[1] Shepherds have been lowered down to the beach to recover the corpses of unlucky sheep, but I know of no printed reference to this cave, and history does not record who was the first to take the sensational stride on to the Pinnacle, climb down the crack and discover the Cave by crawling into the low tunnel at the foot of the fall and up the 10 ft. bank of gravel inside. Rare visitors followed and, by a level dry passage of 30 yds., came to where a stream falls in and round four or five bends to a great shaft or pitch. Finally Mr. Haworth’s party descended this – the First Pitch – and found another great obstacle beyond. There is an outlet somewhere in the floor of the Mere – for so we have christened the pool, though there is good reason to believe the beck itself takes its name from some local word – but the water-level generally stands well above the entrance to the Cave, and the main flow is over the gravel bank inside and forward, by waterfall, pool and soak, chamber and crack, until, after uniting with the smaller stream inside and with all the other waters of Chapel-le-Dale, it comes to light at God’s Bridge, in the valley, 500 ft. below.

Here then was a pot-hole which offered sport indeed – all the fascination of the unknown and all the difficulty of an unclimbed peak. Nor has its conquest been easy – indeed a regular siege has been necessary. Each Whitsuntide since 1907, a little band of mountaineering men have attacked, or threatened it; fresh cragsmen from this Club have filled the gaps from time to time, and its captors were, in the end, almost to a man, at once engineers and mountaineers. Three seasons did we get into the Cave, five times was the attack delivered, but success only attended a combination of spade work and good luck, with a thorough knowledge of the water-system.

Payne first came across Mere Gill Hole in 1905, and forthwith began with enthusiasm to collect a working force. Next year he brought myself and others on a glorious camping trip to Ingleborough and Gragreth and showed us Mere Gill, promising us a pot-hole inside with a single drop of fabulous depth.

At Whitsuntide, 1907, Payne organized our first camp at Mere Gill. Mrs. and Miss. Payne came, and Clarke, Williamson, Hoessly and myself. Mr. Kilburn, of the Hill Inn, brought his cart for the first time up the steep track on the scarp above Souther Scales, and found it very difficult. That camp is still remembered as the infamous “Cold Camp.” How it froze and blew, and what devices we tried to keep warm! How some people burnt themselves with hot stones, and how comfortably we went to sleep, to wake up shivering at 2.30 a.m., and how at length Payne, the resourceful, gave the less hardy the right tip, and I slept warmly the last night under a blanket made up of 300 ft. of rope!

This was a mere reconnoitring expedition; the mouth of the Cave was far under water and our operations were more amusing than serious. We visited Douk Cave, found Far Douk, and let Hoessly down over the big pitch, to be nearly battered to bits by the waterfall before we hauled him back. Has anyone explored the latter cave in the last ten years? We made, too, our first useful discovery about the Mere Gill waters – how to turn the beck so that it falls over the Pinnacle into the Mere.

In 1908 the weather was favourable and our partially successful attack is recorded in this Journal (vol. II, p. 312). With four men on the drag-ropes the heavily laden cart went at a trot up the scarp above Souther Scales, and Hoessly brought two new men, Boyd and Oechlin, to make good our losses. The latter, an absolute stranger to the district, arrived at 1 a.m., having made a bee-line for our beacon in the dark from somewhere south of Ribblehead Station, over scores of walls and miles of scars.

Inside the Cave there was only a reasonable amount of water flowing over the First Pitch, which is some 60 ft. in all, with a large platform three-fourths of the way down. There are also two good ledges, and, if you are clever and quick, you may not get very wet. Hoessly did a wonderful thing here in estimating and sawing off exactly the right length for the beam which we jammed across the shaft to take the pulley for the body-line. Out of the chamber at the foot of the pitch, over a little pool which once successfully engulfed and robbed us of two pulley-blocks, round a sharp corner, through a deep pool and by a narrow but very high winding passage, we followed the water to the big pool with the smooth rock slide just before the Second Pitch. Roped, I slid down in safety and turned to warn Hoessly. He came at it fast, away went his feet, and he slid on his back into the pool. For one brief moment I saw above the water, at one end a boot, at the other a hand grasping a lighted candle, then both disappeared. That pool is known as “Hoessly’s Bath” to this day.

To the Second Pitch we dragged the end of the very long rope which had been tied on as a hand-line for the descent of the First Pitch, and then stupidly threw all the slack over the edge. I was the first man to be lowered, and by a marvellous fluke managed to keep a candle alight through the splash and spray of the 90 ft. descent. There is a broad and very damp ledge, 30 ft. Down – we called it Candle Ledge – and a little below one passes through a slanting corner among sharp ribs of rock which have at one time or another damaged every passer-by. A tangle of rope had to be cleared off the Candle Ledge and several coils released on the way down. Hoessly came next and the magnesium light showed us the gigantic hall – the Canyon Hall – into which we had penetrated. Smaller than the Great Chamber of Gaping Ghyll, it impresses me as longer and higher than that of Sell Gill Hole. A few yards further, the stream falls over a 20 ft. pitch, and from a chockstone above we could see a clean cut fissure – now called the Canyon – running straight away from us, and cutting deeply into what appeared at First sight to be the Hoof of the Canyon Hall.

This was our limit for that day, but, as the Mere continued to fall, in spite of a wet and miserable night, Hoessly and I were lowered again next day. When the first man climbed under the chockstone into the Canyon, and went on lowering himself into the water till he was up to the neck, it looked, for a time, as if it would be necessary to swim, but the pool was deepest at that point, and after another bit of climbing and more pools, to be crossed with care, we went on, roped together, down what seemed a huge length of perfectly straight passage, in a state of wild excitement – for this was entirely unknown ground – till we came to another great pool and, shortly, to where the Canyon ends at a third great descent. In the glare of the magnesium it was possible to make out a platform, 20 ft. down, and a huge shaft to the right. The roof was still an enormous distance overhead. The wonderful thing about the Canyon Hall is that it runs right into the mountain for a good 100 yds. in a direct line with the rift on the surface. We tried to persuade the three men above to send us down another man, but they very wisely declined. Strong men though they were, the hauling at the entrance to the passage was round so many bends that there was not much reserve strength. So Hoessly and I turned to expiate our own carelessness of the day before by undoing the most awful tangle of rope I have ever seen. It was thick rope and wet, and we suffered many plunge-baths in the inevitable pool and a continuous shower from the fall before we got it all clear. Nearly ten hours had been spent underground before, greatly to the relief of the ladies, we returned to daylight with all our tackle, very tired – and very clean.

A month later Williamson gathered a large party for a night attack at a time when the Mere was very low. Five men, including Erik Addyman, Hazard and Boyd, traversed the Canyon and reached the head of the Third Pitch, but the further attack failed, and it was clear that the last of the great Ingleborough pot-holes would never give in to any but a properly organized party with plenty of time and with each man thoroughly acquainted with his job. One good result, however, of this attempt was that Addyman and Hazard fell under the spell, and were keen to carry the exploration to its end. It was they who, by discovering some of the sinks in the bed of the Beck by which water reaches the inside stream and encouraging the Beck to flow into them, found that the supply to the Mere could be cut off early in dry times. The water was, in consequence, lower that summer (1908) than it had ever been before, and in 1910 the Mere was so depleted by this method that, but for the stream at the north end, it might have dried up altogether.

There was never any chance of entering the cave at Whitsuntide, 1909, so we joined the Gaping Ghyll Camp, and, with two of our party down below during the flood (Y.R.C.J., vol. III., p. 67), and the rest, including our ladies, among the workers outside, we had quite enough excitement to last the year.

In 1910 we camped as usual, intending to do minor pots. Never were we so strong. We had lost the two Swiss, Hoessly and Oechlin, who had left the North, but we had found a sixth man of the right sort in Stobart; and my brother came, as he said, to see us work. The accident to Boyd in Sunset Hole (Y.R.C.J., vol. III., p. 177) was a painful shock, and his absence in later expeditions a severe loss.

Mere Gill Hole had now become an enthralling problem. Whenever any of the five men keen to see the thing through got together it was a topic which lasted for hours. It was clear that the whole of the small party must be got down the big Second Pitch, and to do this rope ladders must be used. On the other hand, none of us thought this safe because of the distance to be climbed in the fall. Addyman came in here with the brilliant suggestion, which was the key to our ultimate success, that it might be possible to divert the Beck where it leaves a little gill, crosses some gravel and takes a more open course. Direct assaults having failed, the engineers now took up the siege and began by opening trenches. Some weeks before Whitsuntide, 1911, Addyman and Stobart surveyed a trench as far as the ridge between two big sink holes on the surface and on the side of the wall further away from Mere Gill Hole, and the farmer dug it out for us – at the critical point through stiff clay. With Barstow’s generous assistance, they also made seven rope ladders, and, after destroying every foot of untarred rope except our climbing ropes, we had 1,200 ft. of tarred rope. Numerous people were asked to join us, but Mere Gill Hole has a just reputation for being very wet, and the one accord with which they all began to make excuse became quite laughable. At Whitsuntide, 1911, the weather was lovely, though, owing to heavy thunderstorms, the Mere was nearly up to the Cave. The only drawback was that two men had to leave on Monday night but, on the other hand, there was Coronation Week to look forward to for a second attempt if the first failed. From midday on Saturday we laboured at deepening Addyman’s trench and building up a solid dam across the gravel bed. The water was found to run by one of the sinks down to the First Pitch, so we promptly turned it into the other sink. Three hours’ work sufficed to rig a new beam on the First Pitch, hang the ladders and get much of the tackle down. At the foot of the pitch the whole of the trench-water appeared, so that it was clear the trench must be carried further. After supper we all set to with what energy we could muster. Stobart and Addyman worked like giants till nearly 11p.m., and carried a shallow trench some distance away from the sinks to various holes which we hoped would convey the water to the Sunset Hole system. There was still a lot of tackle to send down when we got to work towards noon next day, including that awkward thing, a beam. With the recollection of Sunset Hole still fresh in our minds, the most extreme care was taken, but the ladders were finally settled on the Second Pitch, and lashed to a big chockstone behind Hoessly’s Bath. The waterfall, however, was very successful in putting out the lights, and it was 5 pm. before things began to come down the Second Pitch, but in the end the beam, three ladders and much rope were carried along the Canyon. One ladder was recovered with much difficulty from the recesses of a pool. For some reason we preferred to secure the ladders to the beam though it was difficult to fix. Hazard found the ladders too short at the first attempt, and at the second it was deemed advisable for two men to watch the beam, so of course the safety line chose to become tangled and before it could be cleared Addyman, who had got down nearly to the bottom, preferred to return. The work and the wettings had taken so much out of us that we now turned back, leaving the tackle in various safe places, and reached the surface at 11 p.m. on an exquisite evening.

Next morning all were very weary and Payne was fated to spend the next night in the train, but the other four pulled themselves together for another try. In two hours we reached the old place at the far end of the Canyon. Three ladders were sent over the Third Pitch, and Stobart and I went down the mighty shaft in which the Canyon ends – a wonderful descent of nearly 100 ft. in all, 70 ft. of it straight down the smooth wall below the platform. For the first time after leaving the top passage a roof can be seen when stooping to follow the stream. After going 60 yds. along the stream we stopped at a smooth pitch above a huge pool, where the aneroid showed us to be 410 ft. below the surface. It was nearly 4 p.m., time was up, and we turned back to the herculean task of dragging the tackle to daylight. Stobart left at 7 p.m. for Leeds but by 9 p.m. everything except the ladders was out on the moor. The ladders required yet another three trying hours’ work next day from three tired men.

Our defeat on this occasion was simply due to the inability of so small a force to crowd both trenching and exploring into the fifty hours available, but our Coronation Week experiences were even more galling and in the year 1911 almost incredible. The weather was doubtful all the week and on Thursday too wet for us to venture on any work below, but Friday was fine. We were without Stobart, but found that in pot-holing, as in mountaineering, practice and condition count for much. Every rope had its appointed place and the ladders were handled like toys and passed down as if by machinery. We chanced to have an electric lamp in going order for the second time, and this was of the greatest service to the first man on the ladders. It is a pity these lamps are so troublesome for pot-hole use. In five and a quarter hours the four of us (Addyman, Payne, Hazard and myself) had reached the Third Pitch, left three ladders ready tied and the necessary rope, and in seventy minutes more had returned to the surface. Mere Gill Hole was at our mercy! Perfectly fit and not a bit tired, we turned in with two full days in hand.

But the stars in their courses fought against us. At 2 a.m. the camp awoke to the furious patter of rain drops. All morning the storm raged worse and worse. For twelve hours the trench held back the flooded Beck and turned the moor beyond the wall into a great lake. At 3 p.m. the water topped the dam and the Mere filled up rapidly. For thirty-six hours the rain fell and we had to leave our ropes and ladders to the mercy of the torrents inside. Next week-end we came again only to find the Cave still drowned and it was several weeks before Addyman, by persistent expeditions and with various people, succeeded in recovering all but two or three ladders. One interesting discovery was made on the moor not far from camp – an opening into the tunnel by which the stream P. 101 reaches the Mere. On hands and knees, for nowhere can one stand up, it was followed through a cold stream for two or three hundred yards to a patch of stones where the lonely explorer can rest and restore warmth to his chilled knees. In April, 1912, Stobart and I were crawling hard in this passage for an hour and a half, there and back, and must have nearly reached the Mere before we gave up at a point where the passage is split into two.

The 1912 expedition almost organized itself. We made no further effort to get others besides our five selves, but a born “cave man” offered himself in the person of R. E. Wilson. The ladders were cut up and for the most part reconstructed and two light ladders bought which proved very useful. Everyone was under orders to turn up in camp at the earliest possible time, and at 11 a.m. on Friday I stood, armed with a spade, by Mere Gill Hole. Things could scarcely have been worse. The fine spring weather had broken, the Beck ran at three times its normal good-weather flow and the Mere was at high-water mark. However, the chances were all against our rallying so strong a party again, so the attempt had to be made. Soon after 1 p.m. I had got most of the Beck running into the trench, partly stopped up the Pinnacle watercourse and persuaded the water which stuck to the open bed to go through the various sinks into the Cave: at all events, there would be no waterfall into the Mere. At 2 p.m. there was a shout and Stobart appeared, brandishing an enormous pickaxe. All afternoon he worked furiously – and so did I, at times – building up the dam and digging a broad channel through the gravel bed straight for the trench. One leak under the dam and the streams from the moor still allowed a fair supply of water to enter the Cave. Hunger at last drove us to the Hill Inn and on the way we met Mrs. and Miss Payne coming up ahead of the camp equipment. After the usual strenuous push and pull up the scarp we got settled down in camp the same night. The Mere was falling rapidly but nothing could be done all next day, so we straggled up Ingleborough to show off our costumes, and spent the afternoon, together with Wilson, digging out the trench in the peat and trying to stop the leak in the dam. The other three men (Addyman, Hazard and Payne), and the second cart-load turned up in the afternoon. Hazard had brought several gelignite cartridges, with which he proposed to blow in a second entrance from one of the big sinks next the trench, and the strong men of the party put in their time there thumping the drill. I was severely censured for having turned in the trench-water and left the place extremely dirty. At bedtime there was a little excitement when we found that Hazard expected us to have the gelignite to sleep with us, but he pointed out the awful possibilities of frost and succeeded in overcoming our objections.

The water that evening was just level with the top of the mouth of the Cave and some of us climbed on to the stones which peeped up and enjoyed a lovely view of the water-filled pot. Next morning the entrance was open. Last year’s beam was found still in position and quite sound. All the ladders and most of the tackle were passed down the First Pitch, the lower part of which we passed, dry and unroped, by hanging a ladder from a belay on the left, and the three ladders for the Second Pitch were rigged. All this time the whole of the water which had escaped the trench was pouring into the Cave, and with the Mere only just below the level of the mouth we did not dare to turn it off. Moreover there was not a single electric lamp available and only one acetylene lamp in working order, and this the great spout of waters which shot over the edge threatened to put out. No one volunteered to go into so heavy a fall and get the ladders down this awkward pitch in the dark, so we had reluctantly to give up the idea of rigging the Third Pitch that day.

It was delightful to be out on the surface on such a lovely afternoon, in time for tea, and, as we were short of ladders, three men went over to the Gaping Ghyll camp and had two light ones very kindly lent to them by Wingfield. Stobart had also his first run down Gaping Ghyll.

Mere and beck had fallen very rapidly in the night and on Monday we turned all the water we could by way of the Pinnacle and so reduced the Cave stream very much. Stobart was first down into the Canyon Hall and in clearing the ladders at the awkward place below the ledge cut his hand seriously. At this and the next pitch we had now men enough to allow of one being stationed on the ledge and were thus saved much time and strength in forwarding the bundles, but he got well drenched by our trick of clearing out a certain pool so as to stop the stream for the moment before each climb up or down the ladders. As soon as possible four men pushed on down the Canyon, and one of them, Wilson, was considerably surprised at the depth to which he went in the first and deepest pool. All the channels we had once dug in the silt-banks had filled up but the pools were soon lowered again to a comfortable level. The rotting, mouldy mass of last year’s ladders was flung over the edge and we had everything quite ready before Payne and Addyman arrived. They had been delayed by having to re-lash the pulley for the body-line. Moreover, Payne had thrown down the 200 ft. coil of Alpine rope from Candle Ledge, and it took him a long time to discover that it had disappeared right into a singular and perfectly round little pot-hole close to the foot of the waterfall and to fish it up again from an astonishing depth. Four men, a rope and a ladder were sent down the Third Pitch, but as the only belay was 60 ft. back from the obstacle at which we halted in 1911, the 200 ft. rope was needed. Addyman was lowered over two drops in the stream and sent ahead while the other three were at work. He arrived back just as we were moving on. “A passage of over a quarter of a mile. Try not to be more than an hour !” and he returned to join the other two at the head of the Third Pitch.

So “Forwards!” The smooth pitch needs the rope as a hand-line – it can scarcely be climbed: the huge pool below is passed by an upward traverse on the left: another pitch is descended by ladder – though it could have been climbed: the next huge pool disappears under an extraordinary rock bridge and we take it on the right, bodies half in a bedding-plane and half in the water with feet scrabbling for hold on the vertical walls – two of us, at least, slipped right in: under the bridge we wade to a sandy beach in a lofty chamber, about 450 ft. below the surface – the Pool Chamber: our belongings have dwindled to a rope and a rucksack and we are hungry – but the end is too near for delay: a dry and fairly level side-passage is noticed, but on we go with the stream, along a narrow lofty course of the Douk Cave type, as fast as we can walk: corner after corner is turned: no pitch now to come – or only a small one: someone counts a hundred steps – they are soon over: the prize is ours and the passage echoes to terrific yells and the roar of the chorus:- ” Pot-holers, cragsmen, scramblers!”

High up on the left we see a dry passage, perhaps the one we had refused: beyond a great torrent pours from an opening, 12 ft. above us: I climb to a foothold in the fall, come off, and get a ducking: on again! the torrent making deafening accompaniment to our shouts: a pitch that only requires a bit of chimney-work into a knee-deep pool: a bank of stones held up by a beam, no doubt the one we used in 1908 : the roof descends: the passage widens: the water deepens and becomes still: all at once we feel gravel under our feet: saturation level cannot be far off and the problem of Mere Gill Hole is solved at last!

The sack is left where we have to crawl over some stones, and we move forward, stooping, through deep water: presently we are working along, bodies on a shelf and legs in the water: then we are crawling through a very wide bedding-plane, in the usual uncomfortable way, on elbows and toes, Hazard drawing ahead and Stobart with his damaged hand falling behind: Hazard shouts that he is jammed between floor and roof: the siege is over – and the awful whirlpool promised us by a local farmer is a myth!

We lose no time in the retreat and count 750 long steps to the Pool Chamber, where we wolf our food, a jubilant crew, and drag the tackle back to and up the Third Pitch. Once in the Canyon we scout the half-formed idea ,of abandoning some of our tackle: six men seem infinitely stronger than four: no double or treble journeys this time, and not so much wrapping up of ladders and with a man on the ledge the top bit of each pitch is climbed without the ladder turning round. Of course there is still much hard work and some happenings: Addyman, for instance, after wearing oilskins all day, contrives to tumble into Hoessly’s Bath, but is consoled by the yells of the unfortunate man climbing the ladders through the displaced water.

Wilson, who has laboured all day in the wet like a hardened veteran of many caves, is the first to crawl out into the daylight about 9.30 p.m., ten and a half hours from the start: seven ladders follow, and Addyman’s half-drowned victim brings up the end of the long line of ropes which have to be pulled through the top passage out on to the moor, and is revenged by one coil catching Addyman round the leg and doing him much damage. By 10.40 p.m. everything but the First Pitch tackle is on the moor, wet clothes are doffed for dry, and we sit down to supper. Grand explosions of gelignite and a magnificent illumination with candles celebrate the victory. The ladies as usual assist vigorously in pulling out the endless lengths of rope, and on Tuesday Mrs. Payne went down the First Pitch.

The exploration of the lower reaches of Mere Gill Hole was too hasty to permit of survey-work. One’s impression is that from the end of the Canyon, where the Cave ceases to run into the mountain and the survey ends, the passages take the direction of Sunset Hole or Douk Cave. If so, the long bottom stretch must lead underneath the upper course of Sunset Hole. The total depth which the water descends through the limestone is from 1,260 ft. at the surface of Mere Gill Hole to 750 ft. where it emerges at God’s Bridge. The opening S. 111, close at hand, is stated to be the outlet of the Mere, but it is curious that none of our party have ever seen water flowing from it in the wettest weather.

Two interesting points remain: the dry passage, and the source of the torrent, 460 ft. down. Most of the trench water can be traced quite close up to Braithwaite Wife Hole, and must therefore join the Sunset Hole water. The possible sources of the torrent, therefore, seem to be:- the Mere, an independent stream gathered underground, or the Sunset Hole stream. The second is very unlikely, and the volume seems too large for the Mere outlet, but it must be remembered that the stream P. 101 is pouring in water unchecked. One would like to believe that the torrent is the Sunset Hole stream increased by the trench water. We assume that from the point we reached the united streams soak through low bedding planes and tiny cracks to God’s Bridge, as the Gaping Ghyll water does to Clapham Cave and the Helln Pot water to Turn Dub. It is not likely that anyone will find a way through, but whoever comes after us, will find good sport in Mere Gill Hole. Once the Mere has been well lowered, a party of eight, working underground in two successive gangs, each for a limited time, could complete the exploration and survey in safety and comparative comfort. We wish them luck with so stout an opponent.

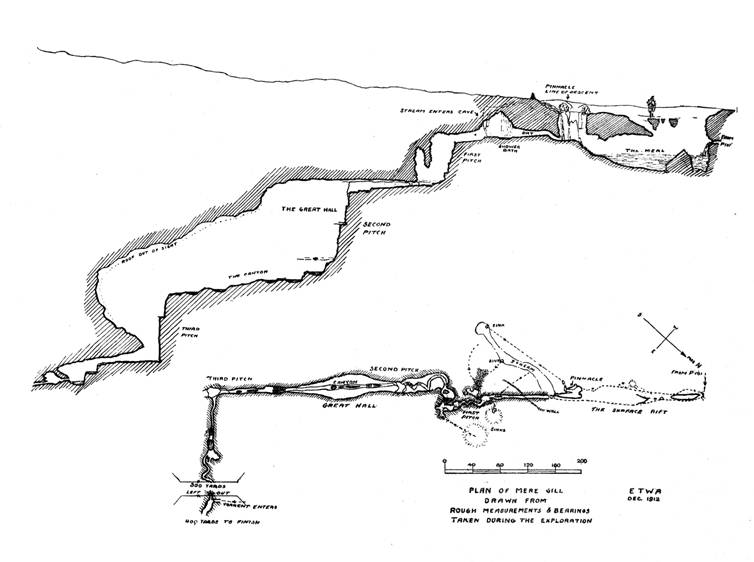

I have to thank Addyman for the accompanying Plan, which was gradually built up and checked by angles and distances measured during his many visits in 1911. It is accurate as far as the head of the Third Pitch.