In Old Tracks

By The Editor.

(Read before the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club, 9th February, 1909.)

Like the girl who, when the extreme ugliness of her “young man” was remarked on, explained that her father had always impressed on her the importance of going through life “with an object,” so Greenwood, in his summer holiday, always climbs with – I had nearly said me, but what I really mean is that he plans out a climb for each working day and trusts to luck and weather for the result.

His “objects” in 1908 were the Zinal Rothhorn, the Dent d’Hérens, the Herbetet and Mt. Blanc by the Midi route, four fine peaks, involving visits to the equally fine valleys of Zermatt, Valpelline, Cogne and Courmayeur – old tracks all of them for us, but not the less pleasant for that.

We reached Zermatt by Lausanne, my favourite way of getting to the Alps, as it gives you glimpses of Paris, the Cote d’Or, Burgundy, the defiles of the Jura and the Lake of Geneva, by daylight, if you are wise, with a good night’s rest at Montreux and the chance of a morning swim in the lake.

I remember Zermatt before the railway, when we had to walk up the lower part of the valley and drive the rest, and though I have been there many times since, and by many routes, it has not lost its charm, indeed, I think it has improved!

Alpine centres are best, of course, when unspoilt, but if they have to be ” spoilt ” – I speak the selfish language of the climber, who, like the deerstalker of the Highlands, thinks the mountains were meant only for him and would, if he could, “make a wilderness and call it peace ” – let them be really and completely ” spoilt,” as Zermatt now is, with concreted streets, sanitary hotels and mountain railways, rather than half spoilt as Zermatt was until lately, with filthy streets, germ-laden hotels and mountain tracks blocked with obstinate mules and kid-booted tourists.

Zermatt is in fact now “regularized” and the daily tide of visitors is dumped at the railway station, housed in comfortable hotels, fed to the sounds of a string orchestra, given clean streets to walk in and shops where anything can be bought from fancy ice-axes to picture postcards, and taken up the Gorner Grat comfortably in the train; leaving the high mountains and the green Alps to their old worshippers. So are all satisfied.

We took the Rimpfischhorn for a training walk, without guide or porter, and thought, as we toiled over the hot slopes of the Findelen valley, of our attempt on that peak in 1891, my first snow climb – except the Breithorn, and of the storm that drove us back from the final rocks. We had no such bad luck this time, and after a lazy afternoon and sleepless night in the little hotel at the Fluh-Alp, which is just the same crazy wooden shanty it was when in 1894 we spent a delightful off-day basking like lizards on the flat rocks in front, we bagged our peak, troubled only by soft snow on the descent and got down to Zermatt in time for dinner. The climb is a fair mixture of snow and rock work, with nothing difficult about it, and we rather envied another man with two guides, who had taken the more sporting way straight from the Adler Pass. I will say nothing of the view – Monte Rosa, Weisshorn, Dom and the rest; nor of the stars and the sunrise: sunrise in the High Alps, as indeed everywhere, is always a new pleasure.

The bite of the afternoon sun had prepared us for the rain next morning, but it cleared up after lunch, and after sending our luggage off to Martigny we went up to the Trift Hotel with Messrs. Raeburn and Ling for the Rothhorn. This detachment from impedimenta is not the least of the many charms of Alpine wandering, and we usually see our bags only long enough to change the labels.

We had no need for guides with such companions who, like the late Mr. Mummery, are brilliant exceptions to the rule that three on a rope is best.

The old Trift Hotel was swept away some years ago by a stone avalanche and is now a mere heap of stones, but a new and larger building has been built a little lower down. The weather had not been promising when we went to bed, but we got up dutifully next morning at 1 a.m., breakfasted, paid the bill and stepped out into the dark only to find it raining steadily, so crept back quietly, and may I add thankfully, to bed. I remember doing the same thing at Simplon and spending one of the small hours reading an odd volume of Punch whilst we gave the weather a chance to clear. I know few things more satisfying for not only have you a sense of duty done but also the prospect of a “long lie” in the morning. And in fact we rolled breakfast and lunch into one, and spent a lazy day reading and keeping up l’entente cordiale with a genial Frenchman and his family and a handsome Dutch lady, who had brought up Kropotkin’s latest work on “Economics” as light reading for a mountain ramble.

We had several companions when we turned out next morning in perfect weather, among them a German lady, garbed in all points like a man (except the hat), and the costume certainly looked more in place here than, as I once saw it, on the dizzy heights of the Montanvert.

We followed the Trift-joch route to the head of the moraine, and I thought of our tramp down it in 1894, when, in our hot youth, we made our first guideless expedition, one of fourteen hours, from Zinal to Zermatt; and of another descent in 1906, when, with two mountain experts, we had failed to find the way up the Trift-horn, and not liking to go back to the Mountet by the Trift-joch, of which we had already detached an appreciable part, came down this way alongside a cataract of stones and returned next day in fear and trembling. Of all mountain passes I know I like this least.

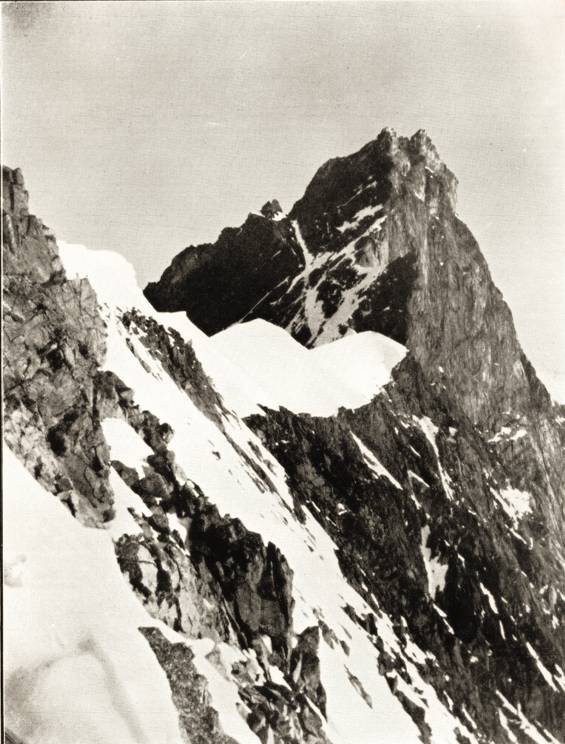

We turned to the right at the head of the moraine, traversed the easy slopes of the Trift Glacier, where the day was heralded by the bursting of a prodigious meteor that lit up the mountain like a flash of lightning, and got on to the rocks at the foot of the eastern ridge of the Rothhorn. Passing along a ridge of snow, up a snow couloir on to the Zinal side, across the slabs which were in good order, up a snow slope and over a broken ridge with tremendous

precipices on our right, we came to the famous corner just below the summit. The passage of this corner is certainly as sensational as they make them, for there is a clear 2,000 feet drop below your heels as you go round, but it is neither difficult nor dangerous and there is plenty of hold.

On the top we found several parties who had come up from Zinal and spent some time enjoying the splendid panorama which was clear all round, even on the Italian side.

The descent by the Zinal ridge is a fine piece of rockwork, always narrow and sometimes steep, but never too difficult, and I enjoyed it much more than the snow ridge which followed, for it was very hot and we had to step up to the knee in the hard-frozen steps of other parties and at every step my sun-shrivelled brain seemed to shake in my skull like a withered nut in its shell.

As we came down to the Mountet Hut I had fearful thoughts of a night spent there two years ago, crouched in one corner of the dépendance among thirty guides, all the climbers’ quarters in the cabane being occupied by a party of Dr. Lunn’s ” mountaineers ” from St. Luc, who had come up to see “high life” for one night only, and of the sleepless vigil I thought I had spent until my companion, Haskett-Smith, asked me next morning if I had heard the avalanches which he averred had been roaring past the hut all night. But Fate was kind and had moved some guide to build a small but very comfortable hotel on the rocks just below the cabane.

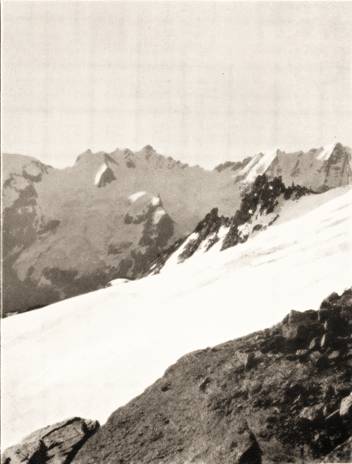

Ling and Raeburn remained here next day to prospect for their climb on the Dent Blanche by the very difficult north-east ridge, which they did the following day,[1] whilst Greenwood and I set off at 5 a.m. to cross the Col du Grand Cornier to Ferpecle. We descended on to the glacier in the grey sunrise, skirted round to the right of the island of rock called the Roc Noir, which is now on Dr. Lunn’s programme of summer excursions, crossed to the foot of the Grand Cornier Glacier, cut steps up its steep slope to the level snowfield beyond and climbed to the watershed by easy rocks on the right. We had a splendid view of the Rothhorn and Weisshorn in the distance and of the tremendous cliffs of the Dent Blanche close at hand, down which a succession of gauze-like films of snow were falling, as though to hide their very real terrors. But such high game was not for us and crossing the ridge to the easy slopes of the glacier on the other side we went down to the moraine and had a long and lazy bask in the hot sunshine. The Dent Blanche towered right above us into the blue, the very embodiment of brute strength, and over its summit hung the baby moon, scarce two days old, like a wisp of cloud in the summer sky. It is memories like this that make an English winter tolerable.

At Bricolla we found a new hotel, so new that the floors were not yet put in, though the beds lay ready outside, and after a pot of tea, rambled gently down to Ferpècle for Sunday.

The little hotel at that place has not altered at all in the last twenty years and is an ideal place for a day off – tiny bedrooms with sunny balconies, a tiny dining room and the tiniest of salons, well stocked with English novels. The young man in charge had doubtless qualified in hotel keeping, now a recognized subject in the curriculum of Swiss education, and, with the help of Messrs. Armour and Maggi, turned out that monotonous sequence of soup, fish, hot meat, cold meat, lettuce leaves in vinegar, nuts and bad coffee, which no self-respecting Swiss innkeeper ever varies. It was the national feast day and some of the inhabitants went down to Hauderes to assist in the celebration, the others had one of their own here, ending in the usual fight. I am sorry to say we missed the prolonged twilight which Raeburn and Ling enjoyed on the summit of the Dent Blanche and have described so vividly – a fitting reward for a great climb.

We set off next morning at 2 a.m. to cross the Col des Bouquetins into Italy, and as the guide-book route, up the far side or true left of the Mont Miné Glacier, was declared to be swept at one point by falling stones we took the local guide to show us the alternative route. We went

down on to the glacier and up its lumpy surface as far as Mont Miné, a huge island of rock with some pretensions to be an independent peak, which stands at the junction of the Mont Miné and Ferpecle Glaciers, and traversing along in the trough between it and the Ferpecle Glacier until we were abreast of the icefall and the Dent Blanche, turned up steep slopes to the summit of the Mont Miné, and paid off the guide. Very dear we thought him and the precious wine which, of course, he had insisted on taking, and which, equally of course, he took back unopened. Crossing over the ridge we got on to the névé of the Mont Miné Glacier, above the icefall, and walked easily along the vast plateau of snow to the frontier, with the Dent des Bouquetins on our right. At one point, where we crossed the track from the Col d’Hérens to the Col de Bertol, our thoughts went back to a tremendous broiling we got there in 1895 when crossing from Zermatt to Arolla. I do not defend the passage of a snow-covered glacier with only two on the rope, but there were no crevasses and the use of a doubled rope reduces the risk to a minimum.

The Za de Zan Glacier falls from the Col in tremendous curves, but we found an easy way down the rocks on the left, and after crossing a rather rotten snow basin and descending some easy couloirs, where the ever-careful Greenwood actually allowed me to unrope and glissade, and after missing our way once in true guideless fashion and fumbling across some rather nasty rock pitches, we came to a well-marked path and a small spout of fresh water. We were glad to have had clear weather for the trip as the way is rather bad to find, and made more so by the maps, which have improved on Nature by inserting a ridge of rock that does not exist, though the written directions in Ball are correct enough.

We never carry much to eat, and our ” elegant sufficiency ” that day had been reduced to four pieces of toast – a Ferpècle speciality – and the inevitable tin of jam, so we did not tarry long over lunch, and going on came quite unexpectedly upon a hut (the Capanna d’Aosta) which the C.A.I, has just put up.

We found there two climbing friends who had come over from Arolla the day before, broken into the hut (the key of which is kept down below at Prarayé), climbed the Dent d’Hérens that morning and were now busily engaged in “siding up,” (as we say in Yorkshire), the remains of what must have been an Epicurean feast. We stood the contrast as long as we could and then made tracks down the glacier to Prarayé, the highest hamlet in the Valpelline, and found good lodgings at a large hotel, which has been built not far from the ancient grange and quaint vaulted cowshed of the Canons of Aosta, where we had stayed in former years.

With a situation so delightful and accommodation so clean it is a pity that so few seem to come here. Scarcely any English names were in the visitors’ book and the only guests besides ourselves were two Italian geologists, who spent their days in rambling about the country and their evenings in copying out their notes. We felt very inefficient members of society in comparison.

We should have liked to spend more time in this delightful spot, but we had not yet done the Dent d’Hérens, so next day we retraced our steps over the rocky barrier which lies above the hotel and up the bare wet glacier to the hut. Being without guide or porter we had to fend for ourselves, and this included splitting the wood, lighting the fire, fetching the water and cleaning up afterwards, duties which very much reduce the desire for a varied menu, just as ladies are supposed, when lunching alone, to prefer what can be brought in on a tray.

We were followed by a party of two young Italians with two guides, all carrying prodigious stores of food, as they intended to remain there for ten days, a phase of mountaineering that does not appeal to me at all. I much prefer not only the greater comfort but the change of interest to be got by wandering from one mountain centre to another.

We had a comfortable night, in fact I had eight hours sleep, a record surely for a hut, and got away next morning at 4 a.m. There was a south wind blowing and some clouds, but no sign of any immediate break-up of the weather as we went down the crest of the moraine below the hut, up a steep snow slope into a side valley on the left and along rolling snowfields, having on our left the steep ridge between this and the Zmutt Glacier, until we reached the foot of the south ridge of the Dent d’Hérens, which divides the Valpelline from the Val Tournanche. Crossing the bergschrund at an easy place, we got on to the south-west face of the mountain and found it a succession of little rock terraces and snow gutters – one could not call them couloirs, the going being less difficult than unpleasant, as the rocks were iced and the snow not in good order. We aimed for a rock pinnacle on the west ridge of the mountain and had got within half an hour of it, going carefully and leaving baby stone men to mark the track, when the weather got worse. Big black clouds were boiling up out of the Val Tournanche and eddying round the summit, though they did not cross the watershed, so we called a council of war – with the usual result. It would have been possible, perhaps, to reach the summit, but there would have been no view, and if the storm had caught us coming down we should have had a bad time. There was no one on the Continent sufficiently interested in our movements to know to a week or two when or where to expect us so, as “members of the Club ” and ” under all the circumstances” and so on, we decided to return, and I think we were well advised, for though we got down to the hut – and to the hotel – dry, the storm broke in the evening and we had such a buffet of wind and rain that we thought the windows had been blown in.

It was still showery when we got away down the valley at noon, and we had to shelter several times, once in particular at the village of Bionaz where I remember stopping in 1894 to get tea at the house of the curé, but they had never heard of tea and to arrive at the price of an omelette had recourse to the market report in last week’s newspaper for the price of eggs and butter. Lower down, at Oyace, there is now quite a good hotel, full of Italian pensionnaires, where we got coffee – they had no tea, and honey, with a mountain pansy tucked into each napkin, by which token and the sticks of gressini we knew we were indeed in Italy. It is a lovely valley all the way down – the church and castle of Oyace, perched on a high rock promontory in right Italian-wise, are especially fine – and we were much better able to appreciate its beauties than in 1894, when we had come over from the Staffel Alp and were pretty well played out before we got down so far.

At the village of Valpelline we hired a carriage and drove down to Aosta in the gloaming. Some day, perhaps, we shall be rushed into that ancient city in the train by way of the already-talked-of tunnel under Mont Blanc, in greater comfort perhaps, but with none of the glamour of the white road, the walled-in convents, the campaniles nodding with the sweet vesper bells and the far-flung gloom of that glorious valley.

We rumbled slowly through the narrow streets, across the spacious market-place to the Post Office for letters and then back to the Hotel Mont Blanc on the western outskirts of the town, with its open galleries and shady courtyard, a very haven of refuge for weary mountaineers.

Next morning was fine and, after a breakfast, of which the toothsome sponge cakes wrapped in silver paper still linger on my mental palate, and a stroll in the town, where I tried in vain to induce a grave ecclesiastic, the sacristan they called him, but he looked the Dean at least, to let me see the gold and ivory treasures of the Cathedral, we drove up the highway, hot and dusty as of yore, as far as Aymaville. We found there a man with a small carriage and leaving our sacks with him set off to walk the rest of the way to Cogne. And what a charming walk it is ! Sometimes high above the torrent, as at Pont d’E1, where the Roman aqueduct, sound as the builder left it, spans the gorge, sometimes alongside the tumbling stream, until we reached the flat meadows where Cogne’s white campanile stands guard at the meeting of the waters.

It was not our first – nor our second – visit to that charming centre, charming years ago in its primitiveness, but changing like so many centres. The old Hotel Grivola, with its crazy galleries and dark salle a manger, frescoed with the owner’s pedigree at full length, has been enlarged and modernized in a half-hearted attempt to meet the rush of Italian tourists who are beginning to find out the beauties of their own country, and another hotel has been opened, where we once had to sleep in the little salon, and both were full. So also was the village, not indeed with tourists but with Alpine troops – fine, stalwart men, who would have been better employed, one thought, in helping the womenfolk in field labour than in dragging mountain batteries up and down the passes in mock warfare. An armed peace can be bought very dearly.

But amid all the changes the women still cling to their quaint hooped petticoats, and with the late J.K.S., we were tempted to exclaim:-

If her anatomy comprised a waist, I did not notice it.

Nor is there any change in the unhealthy houses, imposing enough outside, but inside, all barn and mistal, except the one living room, with tiny fast-shut window and door opening into the barn. No wonder the people look pale and washed out!

Cogne is in fact a spoilt centre at present and will have to go through the same chrysalis stage as Zermatt before it again becomes attractive.

We set off next day, after lunch, for the Herbetet Chalet in the Valnontey, taking with us a porter to carry the bags, a puny creature to look at but a beggar to go. The great Glacier della Tribulazione fills the head of the valley and I looked curiously for the place where, in 1899, with Holmes and my brother, we thought we knew better than Ball and had a very pretty bit of rock and snow work before getting clear. To save time the porter took us up one of the steepest paths I was ever on and we were not sorry to find ourselves at the chalet. It is not a cowherd’s chalet but just a square stone-built hut, like those we see in quarries at home, with a sleeping shelf for five, a table, some benches, a stove, a casserole and a few pots and spoons. High above the murmuring stream it stands in full view of the glaciers at the head of the valley and almost on a level with the Roccia Viva and other minor peaks on the further side.

We dismissed the porter and set to work to fetch water and cut the firewood, or rather to split it with our ice-axes – not so easy to do as it looks, and had just made ourselves comfortable with soup and coffee when four young Italians came up and things got a bit crowded. But they were pleasant fellows and knew how to make themselves happy with weird cooking stoves and other fitments, and we were soon friends.

Venus was shining like a small moon as we left the hut at dawn, and, circling round the glen along a shattered hunting path, came by screes and snowfields to the south Col de l’Herbetet, where we left our bags and started up the easy north ridge of the peak, our Italian friends crossing over for the more difficult ridge on the east.

We climbed by slabby rocks on the left on to the broad face to our right and then over steep snow slopes, with ice underneath, and under overhanging rocks to the shattered summit, and at once found ourselves in a circle of old friends. Far away in the east were the Disgrazia and the Bernina – the former we climbed in 1904, the latter beat us back ignominiously[2]. In the south the Tarentaise, in the west Mont Blanc, and close at hand, on the north, the Grivola, which has foiled us three times, twice by a hot sun, after that awful grind up from Cogne and once by bad weather, and on the south the Grand and Petit Paradis and that fatal ridge between, from which poor Clay and his companions fell in 1904.

The snow was bad on the descent and we took it carefully down to the col, and then, picking up our sacks, traversed the easy glacier on the north and came down in the hot afternoon through the steep pine woods to Dégioz in the Val Savaranche in time for that luxury of mountaineering, a jug of milk and hot water and an hour between the sheets before dinner.

Dégioz is one of the nicest Alpine villages I know. Lying on the eastern slope of the valley it catches all the afternoon sun, at any rate in summer, the houses, unlike those of Cogne, are built on sensible lines and the people look fit and healthy. The little inn has one homely salon for guests and about eight bedrooms, with wooden galleries outside, and a quaint wooden “bridge of sighs” across the narrow street, leading to the landlord’s private house.

There were several Royal Chasseurs standing about and we learnt that the King of Italy was then in the valley for his annual shoot, and that one poor beater had just been knocked down the rocks in trying to turn a frightened bouquetin and killed. We had expected to see some of these fine animals during the day but they and the chamois had no doubt been driven over to the other side of the valley by the beaters. His Majesty, unlike his royal grand- father, is said not to be a keen sportsman and keeps it up only for the sake of giving employment to the people in these valleys. It is at any rate not from any lack of energy or nerve, as witness his recent conduct at Messina.

We left next morning at 8 a.m. and walked down the valley to Villeneuve as the rays of the morning sun were filtering through the pine woods that fringe the summit of the eastern ridge. The path runs high up above the stream and affords a fine view of the head of the main valley and the bare brown uplands of its further side with the snows of Mont Blanc beyond.

At Villeneuve we had lunch and waited for the motor-bus which now runs from Aosta to Courmayeur and reduces that six hours’ agony of a drive to two. But when it did come there was no room and we had to content ourselves with the humble diligénce, and although we chafed at the delay, for the odour of Courmayeur’s flesh pots was already in our nostrils, we had the more time to appreciate the fine scenery – in places almost theatrical. I am thinking more especially of the wooded gorge through which the Val Grisanche forces its way into the main valley, and of the sudden view of Mont Blanc seen through a rock-hewn tunnel.

Near Pré St. Didier we saw a lot of navvies busy on the other side of the stream making what looked like a railway and we thought the Mont Blanc tunnel scheme had actually materialized, but we were assured it was only a new road with a better gradient for the motor-bus, and we tried to believe it.

We reached Courmayeur just in time for dinner and at once found ourselves not only on old tracks but among old friends, mostly Italians, who cling to this charming spot with great fidelity. Nor do I blame them. The village is clean, well-paved and breezy; there is the finest mountain in Europe to look at and the stiffest of climbs up it if you feel that way inclined; and an excellent hotel, the Royal, with cool galleries, spacious salons, first-class cooking, an orchestra for dancing and good company, with no taint of Cook or Lunn or what takes their place in France or Germany. Courmayeur will always be my favourite centre and I hope ” the flat transgression of a schoolboy” which I am thus committing will do nothing to spoil it.

Of course everybody dresses for dinner and the ladies put on their best bibs and tuckers, but they made allowance for vagrants like ourselves who could not boast of two changes of raiment – or even of one, and gave me at any rate a good time – Greenwood does not dance.

I suppose I ought to have sent a dress suit on ahead but I had in mind what happened in 1899 to an Italian friend who had gone up with us to the Victor Emmanuel Hut for the Grand Paradis. We had sent our luggage round by the Col de Nivolet on a mule, and the animal had the bad taste to roll in the snow on the way and when the bags arrived my friend found his newly purchased haberdashery a soaking mess of starch and linen and spent all next day in drying them.

We had been lucky so far in carrying out our programme to the letter and Greenwood was anxious to take advantage of the continued fine weather and set off at once for Mont Blanc but I begged hard for one whole day at Capua and he kindly gave way.

We spent the following morning accordingly in idling around and shopping. I have heard, and felt, hard things about the Italian bread and remember once taking out a Yorkshire loaf to Holmes who had been gritting his teeth for some weeks on Italian crusts, but we found here a supply of soft brown bread, which, when eaten with marmalade, was like manna in the wilderness.

After lunch I fell so far from mountaineering grace as to go for a ride in a friend’s motor car to the summit of the Little St. Bernard Pass. But though the trip had few of the merits of a mountain climb it had all, and more than all, its perils.

To be carried up and down those fenceless roads, along dizzy precipices and round hairpin corners, at an average of 25 miles an hour, in a 60 h.p. car with a cargo of six passengers, a 70 h.p. car in front to set the pace and another behind to see that you keep it, startled dogs disappearing over the edge as you slew round the corners, swearing orderlies on prancing chargers, crawling wagons with straggling gas pipes sticking out behind, your companions standing up and shrieking to the sleepy wagoners:- “Ancora due!” (“Still two more to come !”) – there were five cars in the mad procession – and all this through tunnelled gorges and over bare grass slopes where Hannibal perhaps once laboured with his elephants or Napoleon with his tumbrils, was indeed motoring in excelsis! And then the pleasant tea, carried up in Thermos flasks, at the rude inn on the summit, and the delicious cake, rightly called millefleurs, so soft you had to eat it with a spoon; and, for the final touch, a travel-stained car from Paris rolling up the glen and stopping to cool its engine with snow. On its roof was a spare tyre cased in a round band-box, just like that in which our precious cake had been carried up, and I earned great fame as a wit by exclaiming: “Voila, encore un autre gateau qui arrive!”

But we had not come out to the Alps to enjoy ourselves, (as I remember saying to Holmes in 1896 after a fortnight of rain and dancing at Zermatt), and next morning we strolled gently up to the Mont Fréty Hotel, or rather to its blackened ruins, for the little hostelry which had been a welcome haven three years before for a weary band , sore spent with toiling over the Col du Géant in a hot sun, had been burnt out in 1907, and was now being rebuilt, and the only shelter was a tin lean-to where we had an omelette and a dubious sausage. I was pleased to meet an old friend, Omer Balley, of Bourg St. Pierre, who, with his brother Jules, led me across the High Level Route in 1893, my first Alpine wanderung.

Two hours up brown pastures and steep rocks brought us to the Rifugio Torino at the top of a couloir down which the workmen, busy in improving the path, were sending cataracts of stones, and a fine row they made.

We had left our sacks for the guides to carry, for we did not care to tackle Mont Blanc on our own, and my friend Mazzucchi, who takes the chamois shooting on this side of the range, had kindly lent us his head guide and chasseur, César Ollier, who is the guide chef, I believe, of Courmayeur, and was with the Duke of the Abruzzi on Ruwenzori. As he could not break his own rules and come alone we took his nephew as second guide.

There is probably no finer outlook from any hut in the Alps and we picked out many old friends: the Combin, the Paradis, the Herbetet, the Dent Parrachée and especially the Ruitor, in whose summit hut I once spent a weird night.[3]

From my wooden bunk I could see the moon blushing red through the blue haze that had settled all round the southern horizon at dusk, and when we left at one o’clock next morning she was in full splendour and we never lit our lanterns. We roped at the door and mounting by the short path to the Col went right across that vast amphitheatre of glaciers, past the rock spires of La Vierge and the tremendous cliffs of Mont Blanc de Tacul to the trough which lies between the latter peak and the Aiguille du Midi, nearly as far as the rude hut where some parties sleep out for our climb. For myself I think the extra comforts of the Torino Hut well worth the extra two hours’ walk from the Col du Géant, at any rate when the snow is good and with such a moon as we had.

Turning to the left we mounted by a very steep snow slope and circling round to the left reached the summit of the Tacul (14,000 ft.). Dawn had come, saffron-hued and streaked with bands of cloud, the moon was paling, Venus our morning planet had dwindled to a star, all round lay white wastes of snow, in the depths below ran the dark valley of the Arve and beyond rose the grey mountains of the Chablais. It was a weird scene and perhaps the weirdest touch was a twinkling cluster of lights in one of the furthest valleys, like the Pleiades, “tangled in a silver braid.” Street-lighting must be cheap at Le Fayet, if that was the place, to allow of leaving the street-lamps burning all night.

But the wind had been getting stronger and keener and the short descent to the foot of the Mont Maudit did not warm us much. My finger ends were getting numb and as we sheltered in the séracs and gnawed some food, the guide said:- “Battez les! Battez les!” and proceeded to “bat” them between his, which caused considerable pain but otherwise made no difference. We had no Thermos flask of hot soup to give us courage and as the weather above, so far as we could see, was getting worse, I took it upon myself to order a retreat: wisely, as it turned out, for no one got up that day. Nor had the party that had followed us from the Midi Hut or that other from Chamonix, which we had seen far below us on the Grand Plateau better luck. It was a great disappointment, as we had been beaten back in 1894 from the Italian side by a change of weather above the Bosses, and again from the Chamonix route in 1902 by a high wind in a clear sky after getting as far as the Vallot Cabane. The monarch of mountains is not easily conquered.

It seems but a short way down from here to the Grand Mulets but there is an impassable ice-fall between, so we had to trudge down the Géant Glacier to the Montanvert – and this was Greenwood’s seventh time![4]

We found the séracs in their usual muddled and sloppy state and got through them easily. There were several parties about and we overtook one man with two guides in the middle. He was not an expert and at places where our guide led across without even looking round, his leading guide got above him and held him firm on the rope. It is the possibility of work of this kind that is no doubt taken into account in fixing the mountain tariff and, like tailors’ bills, they who pay cash have to eke out the defaulters.

We paid off the guides below the séracs, and as they had no rope and would not return without one, I had to sell them mine, new that season, at half-price.

And so past the Tank, that well-remembered cistern of fresh water, sacred to the memory of picnics in the long ago, but now, alas, encased in a stone wall, to the Montanvert, full of the usual crowd. The railway has not quite got there yet but I sincerely hope it will next year, for only then will the path to Chamonix be once more clean and pleasant. When tourists insist on coming to a place like the Montanvert as part of a tour by coach and rail, they ought to be brought up and taken back in comfort and safety. In 1893 I saw an old lady, who had been descending on a mule and had swooned and fallen off backwards, lying dead on that very path, and I have no wish to see another.’

We went down past Chamonix to Argentiere and next day by the newly-opened railway to Martigny. It is a fine ride, with a striking descent into the Rhone Valley above Vernayaz, and I could not help contrasting our easy run of three hours and a half with a walk that way in 1889 when it took us a long day.

And so home by way of Lausanne.

[1] A.J., vol. 25, p. 627

[2] Y.R.C.J., vol. 2, pp. 106 et seq.

[3] A.J., vol. 21, p. 215.

[4] Another attempt in 1909 was even more unlucky and after a wet day in the Torino Hut, we had to be content with again crossing the Col du Géant.