Gaping Ghyll Again

By S. W. Cuttriss.

Mr. J. H. Buckley in his account of the descent of Gaping Ghyll in July, 1906, says, “As this was a surveying party only, no further attempt was made to explore the pot-hole, this being left for a future expedition. It is hoped that the exploration of the new passages, which must exist to carry the water from the A bottom of the pot-hole, will lead to further discoveries.” To prove how far these conjectures might be realised was the motive prompting another expedition in the spring of 1907.

For the purpose of this descent twelve men[1] braved the elements under canvas in Arctic weather from May 18th to 21st. Mid sleet and snow showers the usual preliminary work of diverting the surface water into the side passage and preparing the tackle for a descent of the Main Hole by ladders was completed without loss of time.

Additional ladders and ropes were lowered, and by the expenditure of considerable energy, accompanied by groans and ejaculations of a forceful character, these were carried, pushed and dragged along the passages to the top of the subterranean pot-hole. The ladders having been made fast to a convenient mass of rock the descent was made to a depth of about 80 feet when a talus slope of loose rocks was reached, which continued for another 20 feet and formed the bottom of that portion of the chasm. A curious feature of this part of the cave was the presence of several large holes in the vertical flakes of limestone forming the side walls, with the artificial appearance of stage property rather than that of natural caves. At the level of the bottom of the ladders an opening was noticed. An examination revealed a continuation of the pot, and stones being thrown down it was found to contain deep water. Nothing further could be done without additional ladders, so a return was made to the surface.

Next day two more ladders were obtained and the final descent of 60 feet to the surface of the water made by T. S. Booth, A. E. Horn, and C. Hastings in turn. The lower cavity is in the form of a fissure about 10 feet wide and 30 feet long enlarged at the further end by the action of falling water. At the end where the descent was made is a talus of loose stones terminating at the edge of a vertical rock which descends sheer into water about 5 feet below.

The fissure on the opposite side of the water is a mere crack in the rock, and there is not the slightest possibility of further progress being made in that direction. The water was plumbed to a depth of 40 feet without finding a bottom.

Like all the other caverns in Gaping Ghyll this pothole is undoubtedly an enlargement of one of the vertical joints in the rock and probably continues downwards to the base of the limestone. The level of the water, from the measurements taken, is at an elevation of 810 feet, O.D. and taking the moor level at 1,330 feet O.D. this gives a depth of 520 feet from the lip of Gaping Ghyll to the water. A very accurate surveying aneroid taken to the bottom gave a reading of 520 feet from the surface. It will be fair to assume therefore the actual depth from the lip to the water level to be at least 500 feet. As the water where it emerges near the mouth of Clapham Cave is about 805 feet O.D. these measurements thus show only a difference of 5 feet between the two places nearly a mile apart. The water in the pot-hole evidently stands at the saturation level of the limestone, and as past explorations in Clapham Cave and other pot-holes show that water at this low level generally drains away along shallow and nearly horizontal bedding planes there seems little prospect of discovering a practicable passage between Gaping Ghyll and Clapham Cave by following the underground stream.

The deep water in the pot-hole suggests that at one time there may have been an outlet at a much lower level in the valley, probably at the base of the limestone itself, such as can be seen at the present day at Austwick Beck Head. This outlet most likely has been choked up and covered, with glacial drift as there no evidence now exists of any such opening. It would seem that prior to the Glacial Epoch many of the subterranean cavities and their outlets on Ingleborough and the neighbouring hills were of much larger dimensions than we now find them. However, the drift is being gradually washed out again and they should tend to increase rather than diminish in the coming ages.

To turn from speculations to actualities; one of the pleasing incidents of the expedition was the descent made by Mr. R. J. Farrer, who, although he had never previously set foot on a rope ladder, pluckily undertook the arduous task of negotiating 350 feet of “a squirming length of unmanageable awkwardness” and expressed great delight at what he saw underground.

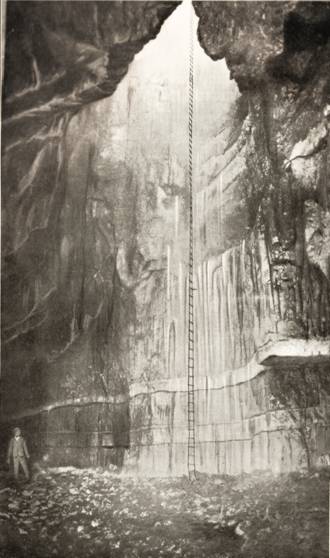

The untiring zeal of Hastings was rewarded by a large number of excellent underground photographs. The fine view of the shaft into the main chamber which, accompanies these notes was only obtained after repeated failures and by the expenditure of an incredible amount of magnesium powder.

A second expedition during 1907 was organized at – literally – a day’s notice and eleven men[2] camped at the Pot on Saturday, September 21st. The objective on this occasion was the investigation of another subterranean pot-hole, the entrance to which had been discovered since the Whitsuntide visit by another party of explorers, at the N.W. end of the Main Chamber.

Owing to the extraordinary dry weather of that month there was no surface water falling down the Main Shaft, the ladder descent being thereby much facilitated.

As on the last few occasions, it was decided that the exploring party should descend at once and remain below all night, while those on the surface would have the opportunity of a night’s rest in camp in order to prepare them for the arduous work of rope-hauling on the morrow. The actual descent was, towards the end, made “in utter darkness, as it was found impossible to keep a candle alight while on the ladders. By 9 o’clock five men were down, with all the necessary tackle, Hastings excelling himself by descending from the Ledge with two rucksacks weighing over 50 pounds on his back.

A supper of hot soup and other delicacies having been disposed of, a move was made to the chamber South of the N.W. slope. Careful examination showed very little change in the floor of this cavern since it was visited in 1896. It is evident that water enters it at times from the main chamber, as below the stalagmite lip, over which the descent by ladder is made, a deep hole has been scooped out amongst the loose rocks there by the descending water. The floor elsewhere is covered with a thick deposit of silt, and in places, close to the walls, it is at a lower level, thus showing as in the main chamber where the water drains away; but no opening through which a person could possibly pass was found.

An oak plank lying on the silt afforded further evidence of the flooding of the cavern by water from the main chamber.

In 1896 though the N.W. slope was carefully examined no passage was found there either. Since then this end of the main chamber has been practically neglected, the work of later exploration being made in the opposite direction. We were therefore surprised to find that there is now a comparatively wide though shallow opening in the N.W. face of the rock wall, which has been exposed by the falling away of some of the loose rocks. On creeping along this for a few yards, a narrow slit like a letter box opening, was found in the floor. By partially undressing we managed to squeeze one by one through the slit into a little cavity about 8 feet deep.

This cavity gave access to a passage which rapidly increased in height as we proceeded. About 60 feet from the Letter Box the floor fell away in a short steep boulder slope and ended abruptly. The fissure continued downwards to a great depth, while the limit of its upward extension could not be seen even with the aid of magnesium light. The sides were pitted and water-worn, showing that a considerable volume of water must at times flow down it from the main chamber. At the time of our visit there was not a trickle anywhere. Stones thrown down told of a rocky bottom, and while the heavy man of the party sat on the end of the ladders at the top of the boulder slope, the leader descended. The bottom, a slope of loose boulders, was reached at a depth of 80 feet, but no outlet could be discovered. The total depth here, from the lip of the Main Shaft, is 440 feet.

The exploration not having occupied so long a time as was anticipated, attention was then given to the old SE. passages to see if any change had taken place in them since they were visited in 1896. As far as the Mud Chamber no material change was apparent, the main passage being quite dry, as heretofore, and with no traces of water having entered it. The other high level outlets from the main chamber at present known, viz., the two at the N.W. end and the S. passage leading to the distant pothole are apparently sufficient to carry off the heaviest flood water. The S.E. passage would thus appear to be the only safe retreat in case any explorers were imprisoned by a great and sudden inrush of water.

In the Mud Chamber a surprise awaited us, for what had once been at steep sloping ridge of silt, like the roof of a house, was now considerably denuded, bare boulders being exposed in place of the ridge. On the west side it is now easy to walk down the wet clay and slippery stones to the bottom of the cavity. On the east side also a considerable amount of silt has disappeared, exposing here and there clean rock faces. The general character of the descent too is quite altered, and as it was evident that to reach the bottom of the cavern more tackle would be required than we had with us, the attempt was reluctantly given up.

Returning to the Main Chamber about 6 a.m. we telephoned to the men at the top announcing our arrival and by 4 p.m. everything was packed up ready for despatching home. The remarkably good time in which the expedition was completed was largely due to the efforts of those who remained on the surface.

Referring to the plan facing page 210 of this volume of the Journal, it is important to remember that none of the passages or caverns shown to the West of the “Junction” have yet been surveyed, that portion of the plan being only a rough outline drawn from hurried notes made during the actual work of exploration.