Speleology:

A Modern Sporting Science.

By E. A. Martel.

(Read before the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club, Nov. 22nd, 1905).

In the most remote ages, as far as we can learn, caves and springs always aroused human curiosity.

Caves, that is, the natural holes in the earth’s upper crust were considered, down to the eighteenth century, merely objects of mystery and terror, fable and fancy.

Springs were deified, consecrated to nymphs, and because of the supply of pure water they afforded, constantly considered one of the best gifts of mother nature.

Modern Science, by putting us in possession of part of the secrets so long retained by underground waters, and by proving their close connection with caves, pot-holes, springs, etc., has singularly altered these ancient beliefs.

I intend to tell you briefly how this particular subject I of underground research and subterranean exploration (” Speleology,” that is the Science of Caves), now carried on in France for some twenty years, has become, as a sub-division common to Geology, Physical Geography, Industry, and above all, Public Health, a very technical, practical and useful branch of human knowledge. But before doing so you must allow me to give you a few data of historical information on the matter.

The first really scientific book on Caves was the “Beschreibung von Neuentdechten Zoolithen” by the German Dr. Esper, published in 1774. The author dealt therein with the large bones found in the Franconian caves in Bavaria, near Bayreuth, especially at Gailenreuth, bones previously thought to be those of an extinct race of human giants. He believed and asserted that they were actually the bones of extinct animals-cave bear, etc. On the basis of these observations the great French scientist Cuvier, after a visit to Gailenreuth, took upon himself to found the science of fossil animals, I mean Palaeontology. Soon after (in 1823), the Englishman Dr. Buckland made himself famous by his book “Reliquiae Diluvianæ,” now of course somewhat out of date, though still valuable because of its account of curious finds and observations in English and Bavarian Caves.

To the Palaeontological side of the subject was soon added the anthropological one by the Belgian Dr. Schmerling in his “Recherches sur les Ossemens Fossiles de la province de Liege 1833-4, and the Frenchman Boucher de Perthes, who both first proved the existence of the fossil quaternary (now called pleistocene or paleolithic) man. Thus another science was formed, the Pre-historic or Paleoethnology.

A list of all the distinguished men and precious books that have made these matters thoroughly known would prove inexhaustible. I would recall only the last and suggestive discoveries of prehistoric paintings and drawings in the Spanish and French Caves of Altamira near Santander, La Mouthe, Font-de-Gaume, and ten others in Périgord. For more than a century and a quarter these dens and grottoes, the whole world over, have been eagerly dug in search of fossil men and beasts. Distinguished English names were also associated with finds of this kind, Lyell with his “Researches on the Existence of Man,” Falconer, Pengelly, Prestwich, Phillips, and many others amongst whom I would specially mention Professor Boyd-Dawkins, whose most valuable hooks “Cave Hunting” (1874) and “Early Man in Britain” (1880) “deserve high praise, and Professor McKenny Hughes, whose lecture “On Caves” to the Victoria Institute in 1887 was, in part, full of really prophetic ideas relative to underground waters, ideas which have been proved practically true by actual exploration since its delivery. But if it be true to say that other observations had been made previously in caves, such as those on their special kinds of fauna, to which space will not allow me to refer, it must be acknowledged that concerning Geology and Hydrology – the true origins und the real functions of caves as waterways and water reservoirs – so many things were, up to the last twenty yours, unknown or wrongly explained, that since 1883 in Austria and 1888 in France, Speleology has given us a quite unexpected harvest of new facts. This process was realized by special and dangerous explorations, by the descents of huge natural pits-in England known as “pot holes” and on the continent generally as “abysses” and also by navigation of underground rivers, too deep, too long and too dark to be swum or waded.

Of course, many previous attempts of the kind, some quite successful, were long ago made in such pits.

Macocha (Moravia) in 1748 by Nagel, Eldon Hole (Derbyshire) in 1770 by Lloyd, Tindoul (France) in 81783 by Carnus, Trébic (Austria) in 1840, by Lindner, Alum Pot (Yorkshire) by Birkbeck and Metcalfe (1867-8) and by Professor Boyd-Dawkins (1870) and Piuka Jama (Austria) by Schmidl in 1852, but all these pits were at least dimly lighted down to the bottom, except the Trébic one, nearly 1050 feet deep. The descent of this, the deepest of all abysses yet descended, was however, accomplished as an industrial hydraulic undertaking after eleven months of hard manual labour.

Concerning rivers also, the Austrian Dr. Schmidl long held the record for underground canoeing by his splendid finds in the Adelsberg district in the middle of the last century, as described in a most excellent work “Die Hohle von Adelsberg” (1854). But in spite of the efforts of these worthy pioneers, the largest and the most instructive parts of caves, pot-holes and underground rivers remained, and still remain in abundance, to be discovered and explained. It is admitted that the exploits of the three Austrian tourists, Hanke, Muller and Marinitsch opened the way in 1883 to a new kind of deep 8 exploration by succeeding in visiting the grand abyss of Kacna _Iama exactly 1000 feet deep, and the colossal river of the Recca in St. Canzian, under roofs 300 feet high and over waterfalls of 30 feet. Though” begun over 67 years ago (in 1839), all the recesses of these two huge cavities have not been entirely explored, and even 3 years ago (1904) a magnificent stalactite cave was found very high in the vaults of the Recca Grotto. In 1886 the Austrian Government ordered investigations to be officially pursued in Karst and Bosnian-Herzegóvina by the Engineers Putick, Hrasky, Ballif, and others for the purpose of preventing floods etc. The work of these three Austrian cave hunters was the signal for a really methodical organization for the pursuit of underground explorations and especially for my own, begun in 1888, ` and since then annually pursued through the whole of France and the chief countries of Europe.

It would take too long to give other names and dates: I will only claim for myself the idea of using for Speleological purposes the telephone (to go down the abysses) and the folding canvas canoe to paddle through both lakes and rivers. Most necessary and useful these rticles have proved, leading from time to time to the discovery of some mysterious marvel or some valuable fact of scientific importance. The boats are of different patterns, made by Osgood & Co., of Battle Creek, Mich: King, of Kalamazoo, Mich: and others in America, followed by Berthon[1] and others in France and Europe. They weigh from 40 to 60 pounds, can be put together or taken apart in a few minutes and packed either in a wooden box or in canvas bags. Wherever an underground passage is found to be barred by deep pool or stream we have the boat lowered down, put it together, and paddle on into the unknown darkness.

In deep chasms, generally somewhat widened at their base, the voice gets lost in its own echo, words becoming quite unintelligible at a depth of from 100 to 150 feet. This inconvenience much hampered my first explorations in 1888, but the following year we obtained striking results with the aid of a telephone, using a very light apparatus (14 ounces in weight and 3 inches in diameter) and as much as 1,000 feet of double copper telephone wire. Thus our words carried clear and distinct from the bowels of the earth, linking the explorers, far from sight, with their comrades in the sunlight above. This, I believe, was the first application of folding boats and telephone to L underground exploration. I have not heard that the latter has yet been used for this purpose in America, but I am sure that it will there prove successful.

And now I turn to two important results (among many others) of the notable feats of modern Speleology during the last twenty years. Putting aside all the newly ascertained facts about the formation and origin of caves, such as had been foreseen by Daubrél, Hughes and Boyd-Dawkins whose exact theories received the most definite and practical confirmation, I will deal with only these two somewhat terrifying proposals.

(1). A very great number of so-called springs, that is, up-risings of clear water, apparently pure and suitable for drinking, are not real purified springs, but often poisonous waters contaminated by exterior pollutions, and holding the germs of most dangerous maladies, such as cholera, typhoid fever, diphtheria, etc.

(2). Our old Earth is getting dry over the greater part of its surface; water sinks in it through the everywhere widening and deepening cracks, joints and faults of the rocks to unknown depths; everywhere growls the terrible threat of a shortness of water ; humanity will die of thirst! This we can confidently assert and forecast. How can it be shown and proved?

Simply by this fact, that the greater part of the earth’s crust is composed of cracked rocks, impervious in themselves, but quite traversable by water through their innumerable crevices. Limestone (of all geological ages) and chalk are specially affected by this characteristic and are also typical ground for caves, but certain crystalline rocks, even granite and porphyry, are also cracked, and from this fact two consequences have resulted. The first and most immediate one is, that all waters, either rainfall, streams, or rivers swallowed up, by rock fissures, carry with them all the impurities they have collected on the surface of the ground. The worst kinds of pollution, microbe and ptomaine, coming from dung and sewers, from unhealthy people, or dead beasts, from cemeteries and every sort of sewage, are freely introduced into the caves and underground rivers so numerous in limestone and chalk districts. There they cannot become filtered since the crevices are too large to allow it, and such filtering can only be accomplished by fine sand. In other words, cracked rocks are not filters, and water pouring out of them at the foot of table land or mountain contains the whole of the pollutions swallowed higher up by the pot-holes and lesser crevices. It is now proved throughout the whole world that those seemingly clear springs so large and abundant in limestone districts are deceptions, not actual springs, and not pure drinking water suitable for the supply of cities. I no longer give to such risings the name of springs, but of resurgences, from the Latin re-surgere, a more or less polluted flood which comes from the open air and returns to this same air, lower down, after an underground journey, shorter or longer, but (with very few exceptions) quite lacking the purity which it was previously everywhere thought to possess. In France geologists have recognized these facts and accepted this change of name for a limestone spring to resurgence, and the French Government, anxious about this new scientific announcement, five years ago established decrees and laws for the protection and examination of drinking waters. Even in the smallest village in France, a person is not allowed to draw water from a spring or to dig a well without it having been previously examined and reported on by an officially appointed geologist and an acknowledged bacteriologist, who both decide whether the particular water may be used or not for drinking purposes. It is also forbidden, under severe penalty, to throw dead animals into the depths (now in some parts fathomed and visited), of these abysses or pot-holes, which more or less directly communicate with the reservoirs or springs. It was my great satisfaction, after long subterranean work, to see this conclusion so publicly acted upon. Much of course still remains to be done in this way for the greater benefit of the public health, but these matters are going on satisfactorily, though slowly. Two years ago I was called to the Western Caucasus for researches of this kind on the beautiful eastern shores of the Black Sea, and in the summer of 1905, the French Government gave me a mission for an important and most interesting water investigation concerning the large town of Marseilles and part of the Pyrenees. Perhaps in England, where it is usual to drink artificially filtered river water, facts of this kind may be considered less important: but this custom gives rise to inconvenience and sometimes danger, as huge artificial filters are most costly and subject to occasional accident. Good spring water always remains the best of all; but it must be most carefully chosen, and this proves now to be immensely difficult throughout the greater part of the geological formations.

The second consequence of the rock cracks is a gradually increasing shortness of water. England also suffers greviously from this inconvenience, and I have read much about it in the report of the Commission on Water Supply appointed by the British Association and in the excellent papers of Messrs. Whitaker, Cartwright and others. Many think, I know, that excessive industrial pumping from underground water is the cause of this shortness. Partly it may be, as well as from other causes, the absence of snow for several years, deforestation, the present diminution of rain – according to the famous Bruckner’s period of 15 years dry and 15 years wet (a theory with which I am not in agreement), the increase of land culture, which augments evaporation, etc. But I think, and have found everywhere, that the deepening and widening of rock crevices by water erosion and corrosion, that is, mechanical and chemical destruction, cause water to descend lower and deeper into the bowels of the earth, in such a way that, for France at least, I have plenty of proofs, too numerous to be produced here, of the general lowering of the spring and well levels.

To correct this peril of the shortness of water, to stop its descent, especially through limestone, two means are at hand. Firstly, the making of underground explorations to examine the details and local ways and courses with a view to stopping the water losses, – and secondly, the replanting of trees in order to diminish infiltration and to regulate the outbreak of large and capricious risings. If these two means are not everywhere energetically employed, many centuries will not elapse before, in large parts of the world, men will die of thirst and the earth self perish of dryness. Central Asia and the Sahara already show how dreadful such a future may be, and the reports of the most recent travellers establish the fact that Lake Tchad and other African Lakes have in late years diminished with increasing speed. It would be easy for me (if time allowed) to prove that a process of universal drying up, much quicker than is generally supposed, is, alas, no dream or fancy.

Such are the two practical and most important attainments of Modern Speleology.

Moreover the systematic study of pit and cave streams throws much light on the questions of their origin and natural use. Everywhere it was formerly supposed that the chasms were thousands of feet deep, and that they always communicated with rivers below. This is not so. Such communication exists only in those caves (about 10 to 20 per cent.) the bottoms of which have not been closed by the falling or throwing down, during centuries, of earth, stones, trees, carcasses, and all kinds of rubbish. Very often rain water from above is able to find its way at the bottom through crevices too narrow for man to follow, but it is certain that the limestone pits drain the surface waters, that caves act as cisterns for percolating rivers, and that these underground-born rivers are finally discharged by large so-called springs. On the way, narrow channels or siphons form real water pipes – to be found everywhere – which prevent the cave cisterns from emptying themselves too quickly, and which act exactly like floodgates or bungholes. Such siphons generally stop explorers in their stygian navigations at a greater or less distance either from the mouth of a swallow hole or from the arch of a penetrable cave or spring. I have met them in almost all European water caves, the most typical of all being at Marble Arch Cave near Enniskillen (Ireland).

Natural pits are not generally due to the falling in of the surface, kinds of manholes marking the course of subterranean rivers: they are rather simple fractures enlarged by swallowed water. Many of them, especially in England where the rainfall is heavy, still drain rivers and rain water, conducting them to caves which act as cisterns or stream-beds, the excess discharge forming the so-called springs or risings. But caves of which the complete passage has been made from the swallow down to the resurgence are very scarce; one of the most typical is the Bramabiau in France, with a river half-a-mile long, a difference of level of 300 feet and four miles of lateral caverns which are partly filled up in times of flood.

The Meteorology of caves shows also that their temperature is not always uniform or unchangeable as was so long believed, and the variation of temperature may be used, as I have proved, to distinguish real springs from dangerous resurgences.

This science also concerns large public works, and not long ago the question was asked of my friend and disciple Professor Fournier in Besancon and myself, if dangerous quantities of water were likely to be encountered in piercing the three large tunnels for the Faucille Railway, leading direct from Dijon to Geneva. From our knowledge of underground Jura, we were both led to conclude that such a danger was improbable, and that if nothing like the disastrous hot and cold waters of the Simplon would be found under the Jura. Ten years ago I also went underground successfully in England and Ireland; of this l have only a few words to say, but I returned with this conviction that lots of caves and potholes might in your own country be profitably explored, not so much as a sport – as they have partly been by many courageous tourists and clubmen in Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Somerset, but more in accordance with the new rules of scientific Speleology. The practical and scientific points of view certainly deserve to be still more clearly developed, as is being done everywhere else in Europe.

We will now consider rather this sporting and picturesque side.

Firstly. The methods now practised in descending deep pot-holes and in the exploration of underground rivers previously forbidden to men before the telephone and the portable folding canoe, above referred to, were used:- As the best proof of the efficiency of these new means of investigation I will only mention that, in 1893, they enabled me to discover, through a pit, a prolongation of over a mile of subterranean river and the direct connection between two distant caves in the underground course of the Pinka at Adelsberg, Austria, although this cave had been most accurately investigated by many scientists since 1818, and particularly by the renowned Doctor Schmidl (in 1850).

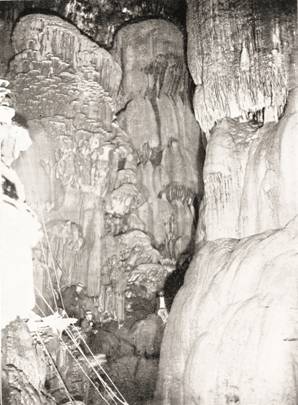

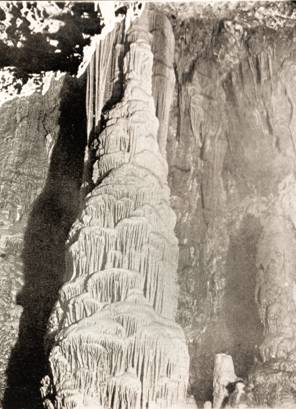

Secondly. A very brief review of the caves newly discovered throughout Europe during the last 20 years (chiefly by Austrians and myself) with their marvellous stalactites and subterranean pools, which far surpass those of the previously most celebrated caverns. Since 1883 Pot-holes or Abysses have been descended to some 1,000 feet, and this forms of course, a most exciting enterprise.

The real danger of descending pot-holes (Which has been called Mountaineering reversed) is the falling of stones detached from the walls of the shaft by the friction of the ropes. The two deepest holes descended, over 1,000 feet, are in Austria, but these are in several stories separated by terraces; the longest in one drop, is that of Jean Nouveau, (Vaucluse, France) a perpendicular shaft of 535 feet, the bottom of which is full of loose rocks through which it proved impossible to pass except by risking a complete and crushing collapse of the entire mass. Two other pits, one in the French Alps and one in the Venetian Alps are reported to measure at least 1,500 feet, but these have not yet been visited. Further, concerning other abysses, many scores of them are over 600 feet, one of the deepest being in France – the Chourun-Martin, in the Alps. I discovered and fathomed this in 1899 to 1,000 feet, and think it probably still 500 feet deeper. We could penetrate it only to a depth of 250 feet on account of the appalling amounts of stone and snow giving way and plunging down the terrible chasm at every motion of the ropes and descending apparatus.

Of course it is no very pleasant sensation to let one’s self be lowered, at the end of a rope, down a very long, quite vertical rope-ladder, as in the 535-foot single-drop shaft of Jean Nouveau, or through several stories of the more usual superimposed and bottle-shaped pits; or, as at the bottom of the 300-foot subterranean waterfall of Gaping Ghyll, very often to find a pool, blocked with huge stones or choked with clay, or perhaps an accumulation of fatal carbonic acid gas, and under a continuous bombardment of pebbles detached from the side of the shaft by the motion of the rope. But what of all these risks and difficulties when such a first descent discloses to the eyes, at the bottom of an abîme, a gigantic reservoir like that of Rabanel (Herault, France), 700 feet deep, or a cavern like that of the above named Gaping Ghyll, or a 4-mile avenue of first rate geological interest such as Bramabiau (Gard, France), or the refreshing grottoes, rivers, and lakes of Padirac, Dargilan, Aven-Armand, in France, or Cueva del Drach (Balearic Islands), the whole gleaming gloriously under the flashing magnesium light, weird to the tourist, exciting to the explorer. These four caves are, with Adelsberg (Austria), Agtelek (Hungary) and St. Canzian (Austria), the most glorious of all known caves, on, account of their ornamental stalactites and stalagmites. Aven Armand (680 feet deep) is the most magnificent of its kind, with its real forest of 400 stone trees varying from 3 to 100 feet in height, the latter the highest stalagmite in the world. Next come the Astronomical Tower, in Agtelek, 80 feet high, the Spires of Dargilan, 60 feet high (all correctly measured with air-balloons),the glories of Calvanen-berg in Adelsberg and the millions of thin needles reflected in the sea-caves of Cueva del Drach. Padirac is perhaps the most charming and majestic of all grottoes, with its underground river a mile-and-a-half long, numerous lakes, vaults up to 300 feet high, most splendid stalagmites and dozens of waterfalls, all now very easy of access by means of staircases, rowing boats and footpaths, and visited by 8,000 tourists a year. Less charmingly ornamental but still grander, with a dreadful subterranean torrent and vaults – also 300 feet high, is the Recca cave at St. Canzian a mile-and-a-half long, whose exploration required sixty-five years (1839-1904) and is perhaps not yet finished.

In England especially, before my own underground researches began, only two pot-holes of known importance, Eldon Hole (Derbyshire) and Alum Pot (Yorkshire) to which I have already referred, appear to have been descended. Many unsuccessful attempts were made in Gaping Ghyll and Rowten Pot (Yorkshire), but since my own lucky first descent of Gaping Ghyll (1st August, 1895) these explorations have taken a most regular, exciting and profitable course in Great Britain. I will not venture to summarise the valuable underground work so well and thoroughly reported in this Journal, of Messrs. Calvert, Gray, Green, Booth, Parsons, Cuttriss, Constantine, Slingsby, Moore, Barran, and others in Yorkshire; Baker and his friends in Derbyshire; Balch, Bamforth in the Mendip Hills (Somerset); Dr. Scharff, Plunkett and Lyster Jameson in Ireland, etc. I will only compliment them on their many courageous undertakings and in wish that they may carry them on with ever increasing success. In the British Isles, certainly, most interesting cave discoveries still remain to be made.

One word more about the gigantic American caverns – Mammoth, Colossal, Wyandotte and others. Certainly they are the largest, though not the finest, existing. For instance, the real dimensions of these caves have been very much over estimated, because no accurate topographical surveys have ever been allowed by their owners, who fear that careful investigation may result in the discovery of new entrances to the caves and thus deprive them, of the annual benefits brought by visitors, It was recently made clear by the enquiries of Dr. Hovey[2], Messrs. Ellsworth Call, Le Couppey, De la Forrest[3] that Mammoth Cave is far from containing the 220 miles of galleries stated in some books of geography, or even the 150 miles estimated by D. D. Owen (Geological Survey of Kentucky, 1856) to which the number was afterwards reduced, and that it is much more likely the whole extent of its known and penetrable corridors and avenues does not exceed a total length of 30 miles, which still leaves Mammoth Cave the longest cave in the world[4]. Wyandotte Cave, reputed to be nearly 24 miles long, appears not to exceed 9 miles. The “bottomless pit” in Mammoth Cave, formerly said to be 200 to 300 feet deep was only 105 feet by Hovey’s measuring line.

In conclusion, for other particulars concerning the special aims and desired extension of scientific cave hunting I would only refer you to the publications of the French Société de Spéléologie[5], founded by myself, at Paris ten years ago, to collect all the information on the subject that was formerly scattered among various publications. The sixty papers already issued by this society under the name of Spelunca (a review of speleology) show plainly that it deals with something more than mere sport, and not only with the matters considered above, but also with the other sciences, palaeontology, and Zoology, thus making it an interesting study and a useful thing in its self.[6]

[1] Berthon was an English clergyman who lived at Romsey in Hants.

[2] “Celebrated American Caverns,” 1882, re-edited 1896.

[3] Quelques grottes des Etats-Unis d’Amerique,” Spelunca, No 35, Novembre, 1903.

[4] The largest cave in Europe (Adelsberg in Austria) is only a little more than 6 miles (10 Kilometers) long; second to it comes the newly discovered Holl Loch (Switzerland) with nearly 6 miles, which may prove the first European cave when the present explorations have been finished; and third, the Agtelek Cave (Hungarian) with 5 ½ miles (8,700 meters.)

[5] 34, Rue de Lille, Paris. Fee for membership 12 shillings a year. Further information may be obtained from the treasurer, M. Lucien Briet, Charly (Aisne), France.

[6] See also E. A. Martel “Les Cevennes” 1890, “Les Abime” 1894,” lrlande et Cavernes Anglaises” 1897, “Padirac” 1899, all published by Delagrave, Paris. “Le Spéléologie,” 1900. “La photographie souterraine,” 1900, both published by Gauthier Velars, Paris. “Le Spéléologie au 20° Siecle,” 1905-6 (Spelunca, Memoires 41-46, 812 pages) “The Descent of Gaping Ghyll,” Alpine Journal, 1895.