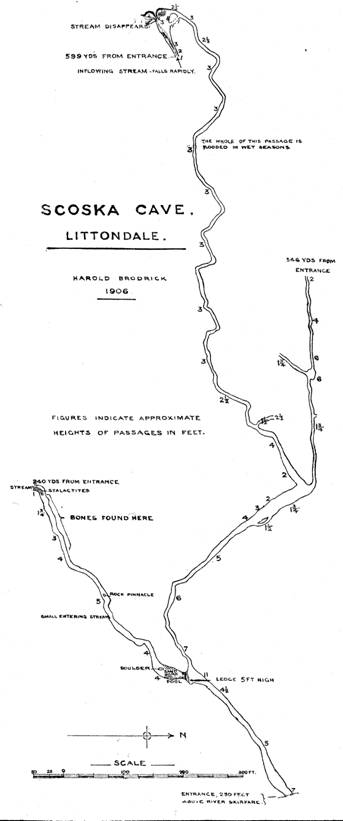

Scoska Cave, Littondale

By Charles A. Hill.

Scoska Cave lies about a mile above the village of Arncliffe, on the S.W. side of the valley, at a height of 250 feet above the river Skirfare. It was until recently practically unknown even to the inhabitants of the district, though the entrance is a conspicuous object on the hillside. The cave mouth opens on the side of a steep rocky slope composed of Carboniferous Limestone thinly covered with stunted trees, and at a height of about 1,000 feet above sea level. It faces N.E., and is 7 feet high x 15 feet broad. In wet seasons a stream trickles out of the cave and falls in a series of small cascades over the cliff face.

Entering the cave one can walk upright for a distance of 75 yards until a point is reached where the passage divides into two; the way to the right is the larger and is the more obvious one to follow, being lofty and quite dry; it continues for something like a quarter of a mile, and seems to go on indefinitely, the roof and the floor gradually coming together until further progress becomes arduous. That to the left from which the stream flows is entered by creeping under an arch about 18 inches high. Then the roof rises and the passage alternates in height from 3 to 5 feet for a distance of about 100 yards; further on it gradually gets lower and lower until the only method of progression is by crawling flat in the stream. Here it was on the first exploration that innumerable stalactites of all sizes had to be broken through to afford a passage; a fact which goes to prove that this portion of the cave had remained undisturbed for many centuries.

The first exploration of the cave was made at the Autumn Meet of the Club in 1905, during which time the first human remains were found at a spot distant some 240 yards from the entrance. These consisted of a Radius, a Vertebra and a portion of a Rib, all lying on the surface.

This interesting discovery naturally stimulated further research, which has been undertaken since on several occasions, and has resulted in the finding of a considerable number of the long bones, but the whole skeleton is as yet far from complete. Most of the bones were scattered along the floor of the cave over a distance of 20 feet, some being almost entirely buried in stalagmite and therefore requiring very careful extraction. They are all of a dark brown colour, more particularly those portions which were exposed; this is probably due to the action of the peaty water flowing through the cave. The stream, which now exists only in times of wet weather, would be responsible for the scattering of the bones.

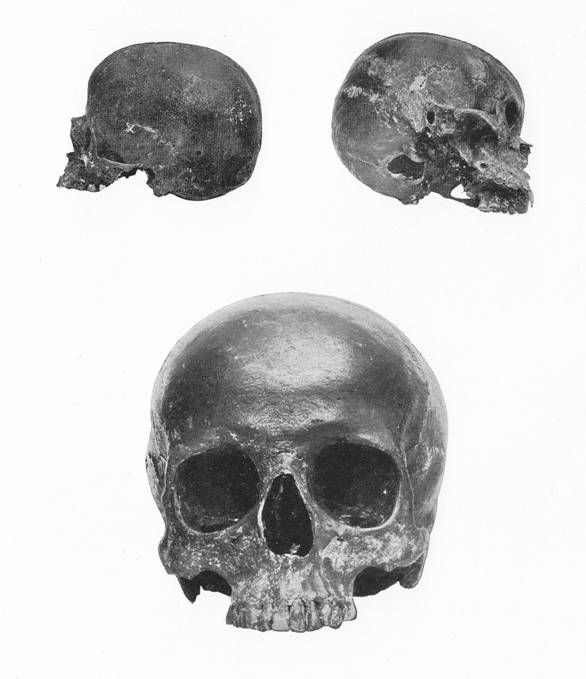

The skull when found was practically imbedded in stalagmite, the cranium being full of sand and grit, so that great care was needed to extract it without damage. It lay at the bottom of a hollow about 18 inches deep, and was covered by a few inches of water.

The most interesting part of the find has undoubtedly been the discovery of the skull, since this affords a ready means of determining the race, sex, and age of the skeleton.

The racial characteristics of any skull are determined from a consideration of its various measurements, these being taken between certain fixed points which it is unnecessary here to enumerate. If the length be divided into the breadth and the result multiplied by 100 a certain figure is obtained which is known as the “Cephalic Index.” Skulls whose Cephalic Index is over 80 are termed “Brachycephalic” or broad-headed, as opposed to the “Dolicocephalic” or long-headed, whose index is under 80.

The Cephalic Index of this skull is 82, whilst the cubical capacity is 1420 cc.; it is, therefore, almost without question that of a Celt of the Bronze Age.

The sex can be ascertained from the conformation of the skull as well as that of the other bones, but for the present we will consider the former only.

On examination of the forehead just above the eyes we find it flattened, the superciliary ridges and frontal sinuses diminutive and not projecting; further, at the base of the skull the mastoid processes are small and the lines of muscular attachment poorly marked. In the male all these are prominent in that they afford a place of adherence for muscles of greater strength. The sex, therefore, is undoubtedly female.

The age can be determined within two definite limits from the following observations. Every skull at birth is made up of a number of separate bones which, as age advances, grow together and coalesce. The jagged line where their adjoining margins fit closely into one another is called a “Suture.” These sutures become obliterated, as the bones unite, at certain definite periods of life. Thus at the base of the skull the junction between the bones known as the Basi-Occipital and the Sphenoid become obliterated at about the age of 24. In the skull found there is no suture, therefore her age was over 24. Obliteration of the junction between the Occipital and the two Parietal bones – known as the Sagittal or InterParietal suture – commences at about the age of 45. In this skull there is no sign of obliteration, therefore her age was under 45.

So far then we can definitely state that her age was over 24 and under 45. To fix it more accurately we must examine the condition of the teeth. With the exception of the two back molars, which have dropped out since death, all the teeth in the upper jaw are preserved (the lower jaw has not yet been found). These are perfect, showing no signs of decay, but are much worn down and exhibit marks of considerable attrition, their enamel being ground away, evidently from the use of hard and gritty food. This condition is especially noticeable in the back teeth (bicuspids and molars), which are concerned wholly with mastication. This clue justifies the conclusion that her age was rather towards the later than the earlier period of life, and therefore somewhere about 40.

The skull, therefore, is that of a female about 40 years of age.

It is known that the Celts persisted in Craven up to the end of the Roman occupation of Britain, so that the age of the skeleton may be anything from 1,500 to 2,000 years.

When originally found the skull was thickly encrusted with stalagmite. On removing this a most interesting discovery was made, and one which throws considerable light on the probable cause of death as well as providing reason for the present situation of the remains, so remote from the cave mouth. Just above the right mastoid process is a small irregularly shaped hole, produced probably by a blow from some blunt weapon such as a flint axe, spear, or arrow, which has caused destruction of the outer table of the skull and perforation of the inner. Such a wound might not bring about immediate death but would ultimately do so from compression of the brain, either by depression of the fragments or by haemorrhage.

The possible history is as follows:- This woman after receiving a wound on the head made her way up the cave under the stress of some strong emotion such as fear, and taking to the passage which is the less obvious of the two crawled to its uttermost extremity and there died. The idea of burial may, I think, be excluded for many reasons.

Another point of interest, which appeals perhaps more particularly to the student of medicine, is the shape of the hard palate. Its arch is abnormally high, whilst the dental margin is greatly contracted at its hinder end. This condition is brought about by nasal obstruction in infancy, due to the disease known as “Adenoid growths of the Naso-Pharynx.” As a result of this abnormal arching of the hard palate the septum, or central division of the nose, becomes deflected or bent to one or other side. ln this instance the nasal septum is bent to the right, hence the left nostril is larger than the right. To fill up the gap so caused the turbinal bone (one of the bones forming the outer wall of the nostril) becomes enlarged or hypertrophied, and is so found in this instance.

With the nasal bone set almost at right angles to the face, and the teeth of the upper jaw projecting forwards this woman could hardly be termed “a thing of beauty” according to our present ideas.

The next point of interest to be determined is her height. This can be ascertained from the measurement of several of the long bones, viz:- the Tibia or shin bone, the Humerus or arm bone, and the Radius or fore-arm bone. The proportion which these several bones bear to the average stature of a woman is as follows:-

| Tibia | 22.1 per cent.of the stature. |

| Humerus | 19.9 ,, ,, ,, |

| Radius | 14.3 ,, ,, ,, |

Calculating from these data the height as determined from the measurements of the several bones is as follows:-

| Name of Bone. | Length in inches. | Height. |

| Tibia | 14 | 63.3 |

| Humerus | 12.5 | 62.8 |

| Radius | 9 | 62.9 |

Average height … 63 inches.

We can state therefore that her height was about 5 feet 3 inches. The Tibiæ or shin bones exhibit in a marked degree the condition known as “Platycnemism.” This condition is frequently met with in prehistoric Tibia, though not in those of civilised nations of the present day. It occurs however in the bush tribes of South Africa as well as in other primitive races, and may be described thus[1]:-

The oblique ridge, a point of muscular attachment which runs down the back of the bone about its upper third, is unduly prominent, so that at this point it has a two-edged appearance instead of being roughly triangular in section. In other words the bone is thin, measured sideways, while from back to front it measures more than that of a modern Tibia.

There are various indications in the long bones which point to the sex being female. Thus in the Femur, the neck is set at a lower angle than in the male, averaging 118° ; the degree of obliquity of the shaft is greater so as to allow for the increased breadth of the Pelvis. For the same reason the shaft of the Tibia has a slightly oblique direction downwards and outwards.

The length of the Humerus is 318 mm. The average length of the adult male Humerus is 355 mm. whilst that of the female is 320 mm, to which figure it will be seen it approximates closely.

The following is a complete list of the bones found up to the present, together with the measurements of the skull.

| SKULL. | Length 168 mm | Cephalic Index 82. |

| Breadth 138 mm. | Vertical Index 76. | |

| Height 129 mm. | Cubical Capacity 1420 cc. |

The lower jaw has not been found.

| RIGHT SIDE. | LEFT SIDE. |

| Clavicle. Radius. Ulna. 12th Rib. Tibia. Fibula. Astragalus. 1st Metatarsal. 3rd Metatarsal. |

Humerus. Radius (4in. of the shaft). Ulna. 1st Rib. Os Innominatum Fibula. (A portion only.) Femur. Tibia. Fibula. |

Several other portions of Ribs.

| SIX VERTEBRӔ. | Cervical, 4th or 5th. Dorsal, 5th or 6th. Dorsal, 11th. Dorsal, 12th. Lumbar, 5th. Another Lumbar in fragments. |

[The search for the bones extended over a lengthy period and was carried on by Messrs. Barnes, Botterill, Brodrick, Buckley and myself during a number of short visits. Mr. Barnes was the fortunate finder of the skull. C.A.H]