Slogen

A Day On The Seaward Face

By Harold Raeburn

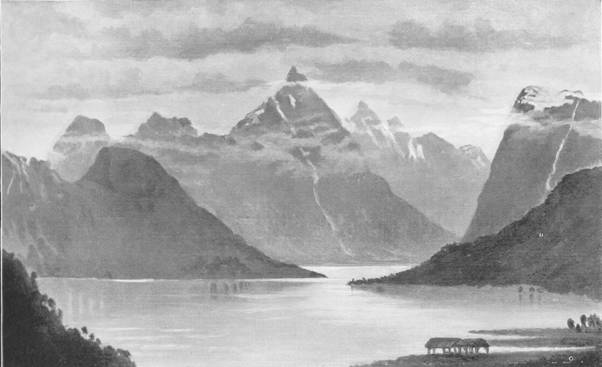

Away up at the head of one of old Norway’s grandest fjords lies the splendid mountain called Slogen. Beautiful it is; does not our English father of Norse mountaineering, Mr. W. C. Slingsby, call Slogen “the most beautiful peak in Norway,” and who has a better authority to speak of its beauties than the man whose foot has first been planted on so many of the highest pinnacles of the “Northern Playground ?” Slingsby says of it, – “From the pass we saw the top 2,000 feet of Slogen, a pyramid so sharp that I have rarely, if ever, seen its equal, either amongst the Chamouni Aiguilles or in the Dolomites.” The sight of Slogen, from whatever point one gets his first view of its soaring horn, is an inspiring spectacle to the mountaineer’s heart. As his eyes follow its noble concave curves, ever steepening as they sweep upwards, his spirits are lifted with those lines, and he resolves that before long his feet must tread the apex of that airy spire.

Slogen is situated at the very head of the Norangsfjord, a branch of the Hjörundfjord. It is one of the highest of the ‘Sondmore Alps,’ a district of sharp peaks and jagged ridges, very different from the monotonous, huge humpy ‘Fjelde’ of the principal Fjords. Here is a district of ‘Tinder’ and ‘Horner,’ of saw-toothed ridges, whereon – as Herr Randers, the author of “Sondmore” has it – “Selv en liniedanser kunde balancere” – only a tightrope walker could balance. Here is also a region of steep glaciers and deep snow-filled gullies, for though relatively low (few of the peaks rising much above 5,000 ft.), yet we are here at 62° N. latitude and the snow line lies at a comparatively low level.

Priestman, Ling and the writer had wandered through the Western Peninsula of Sondmére, and had been lucky enough to annex one or two of those scarce articles now-a-days, even in Norway, – virgin peaks. We had settled for a few days in the extremely comfortable Hotel Union, at Öie, and had done some good climbing, mostly novel, from there. It would never do to leave Öie without ascending Slogen. Unfortunately from our point of view, Slogen, though an impossible looking peak from all sides but one, was on that one side entirely devoid of difficulty. Indeed, as some – people have even been known to speak disrespectfully of the equator – that “menagery lion running round the earth,” as the school child said – so is it with Slogen. The ordinary ascent has been described in the classic phrase of Mr. Mantalini as “one ‘i demn’d horrid grind.” We however, had come to Sondmore in search of novel climbs, and therefore, as we certainly wished to get to the top of Slogen, it was necessary that an entirely new route be selected.

The climbing history of Slogen is not extensive. The first ascent was apparently made by a Norseman, Jon A Klok, and his brother a few years previous to 1884. In that year Slingsby made the second ascent along with his brother-in-law and Jon Klok, and wrote of the peak, “Slogen has one possible route and one only.” No one appeared to care about disproving this till 1899. In August of that year Mr. Armstrong made with Vigdal, the famous Norse guide, a grand though futile eleven hours struggle in the great gully that sweeps up to Klokseggen below the S.W. face. A few weeks later Slingsby, with G. Hastings and A. and E. Todd, had the pleasure, as he says, of “eating his own words,” and did a splendid climb up the grand N. aréte.

This as far as I know has not been repeated, nor had any other attempts been made to get out of the rut of the ordinary way till our visit in July, 1903.

Some hours of idleness on Sunday had been spent by Ling and I in quietly floating on the calm waters of the Norangsfjord.

“Saa Baaden syntes let ophaengt at svaeve

Mid i et Lufthav hvor der ej var bund

Men lige dybt foroven og forneden

Som Jordens Kugle mid i Evigheden”. [1]

“We had studied from thence the tremendous wall of the south west face of the mountain. Given perfect conditions, as now, we came to the conclusion that it might be forced. If that were so it would be the biggest thing in the way of a rock-climb that either of us had set eyes on. On Tuesday, ]uly 28th, the conditions were A. P. -absolutely perfect. Eight days of blazing sun for almost twenty hours a day had removed all traces of ice from the rocks, and the face was for 4,000 feet far too steep to allow of any quantity of snow lodging. Both of us were in good condition after a weeks’ splendid scrambling and climbing. We were prepared if necessary to pass a night, upon the rocks, and last, but not least, we had with us a pair of kletterschuhe, such as are used on the magnesian limestone peaks of S. Tyrol. We resolved to make an attempt, at any rate, to traverse Slogen direct from the sea.

The morning was a lovely one, and already it was hot as Ling and I left the hotel at 7. We walked down the road to the steamer pier and from there turned straight up hill to the foot of the huge series of slabs that here girdle the base of Slogen. These slabs are here and there covered with earth and moss, and were brilliant with the tall, delicate pink flower spikes of saxifrage. We put on the rope at 950 feet and started up the face. At 1,200 feet however it was considered inadvisable to persevere, as the earthy turf on these holdless slabs had thinned out to nothing. A descent was therefore made down to the screes again. Our first objective was to gain the foot of the great buttress which walls in the Armstrong-Vigdal gully on the S. The drainage from this gully pours over these lower slabs in a series of slides and falls about 1,000 feet high. We therefore traversed along below the falls to their west side and restarted the climb at 9.10 a.m., – height by aneroid 900 feet.

We had a hot, stiff fight up here, by steep grassy ledges and through bushes and trees, having often to haul ourselves up overhanging places by the roots and stems of the latter. At 11 o’clock we crossed some slabs on our right and entered the bed of the gully, just above the waterfalls. Here we rested for half-an-hour and had lunch and admired the view, somewhat restricted by the narrowness of the Fjord and the steepness of its containing walls of Slogen and Staalberget; the aneroid gave here 1,900 feet. At 11.30 we crossed the gully and got onto the ridge by a steep chimney. Here the Wall is only about 40 feet in height. Higher up the height of this above the gully rapidly increases, by reason of the ridge’s angle being much greater than that of the gully, till it is nearly 1,000 feet above the gully bed. This wall is nearly vertical on the gully side (indeed in many places it overhangs) all the way up. The next 2,000 feet of climbing, though full of the most interesting and varied rock work, presented nothing of very special difficulty. We were twice forced off the ridge into a gully or chimney on our right and had a little step-cutting occasionally in the masses of hard snow in its pitches. Kletterschuhe were used on one rather awkward slabby traverse into the gully; they were of course useless in the chimney itself as there was water and, slime from the melting snow on its chockstone pitches. Great care was necessary here on the part of the leader, as immense quantities of loose stones lay at the top of each pitch and emphasized very strongly. the advantage of there being only two men on the rope. Somewhat before being driven off the ridge for the first time we made an interesting find. A mountain finch flew out of a crevice – height by aneroid 2,650 feet – from a nest containing five fresh eggs. We took one egg, which was carried safely to Öie but unfortunately went amissing on our long tramp South over Horningdalsrokken and the Justedalsbrae. After four hours’ work (at 3.10 p.m.) we halted a second time and had a second lunch, afternoon tea, or whatever it might be called. The aneroid now registered 3,550 feet.

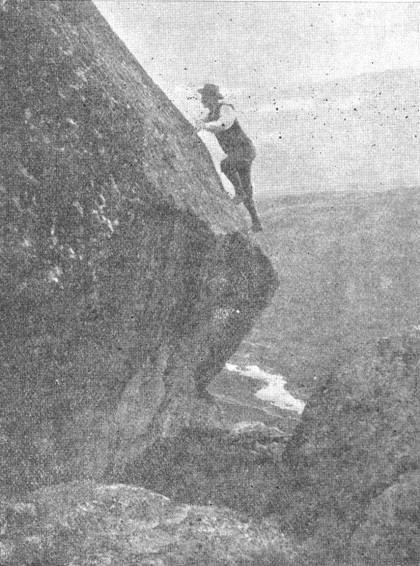

At about 4,000 feet the great ridge began to merge in the almost vertical W. face of the steepest side of Slogen. The climbing became now so crowded with interest and incidents that it is impossible to recall them all. Several times were we almost ‘pounded,’ and without kletterschuhe I do not think we could have gone on. At only one place, however, Ling told me afterwards, did he think we must give up. My opinion, I may state, fully coincided with his, though neither of us hinted as much to each other at the time. Ling was at this time seated astride a spike of rock projecting from the vertical face, the snow of the gully being fully 1,200 feet below, while I vainly endeavoured to drag myself up an overhanging bulge above. No use! even kletterschuhe could find no hold here. The difficulty was finally overcome by a traverse round a crazy corner, where the mining out of half-a-ton of rock alone allowed of a passage being effected. The rock at this part of the climb was decidedly rotten. On the face to our left a great yellow mark 80 feet high by 40 broad showed where a huge rock-fall had recently taken place. The great gully must always be, as Slingsby has rightly pointed out, exceedingly dangerous on account of falling stones. Those we sent down here went whizzing into its snows with the terrific velocity gained in a fall of 1,500 feet.

At length, towards 8 p.m., we reached a slanting ledge where a little snow was able to lodge, and victory appeared in sight. The final line of cliffs however appeared vertical, or overhanging, but we found a chimney, which, higher, thinned out into a deep crack splitting off a huge block from the face. This climbed, we gained a ledge from which another vertical crack sprang upwards, and at last, at 8.30 p.m., we reached the top of the cliffs 50 feet lower than and 100 yards to the E. of the cairn, the aneroid making 5,200 feet. Binding up the rope, we hastened to the cairn. There we spent a glorious half-hour in admiring the magnificent panorama spread before us. The black shadows were creeping up the narrow fjords and dales, filling them with dusky haze; but still a good height above the jagged spears of the N.W. mountain ridges the glorious sun shone in hardly diminished radiance, and even at this height and at this hour the air was warm. From our feet fell down, almost into the laving waters of the Norangsfjord, the vast wall up which we had toiled throughout this long summer day.

The darkening chasm of the Hjörundfjord led the eye westward between range after range of jagged rock-peaks and dazzling snow-ridges to the islands round Aalesund and, further, to the dim blueness of the open Atlantic. Close at hand on the north appeared our peaks of yesterday, the Brekketin and Gjeithorn, with their connecting ridge of fantastic aiguilles soaring above the white folds of the glaciers. To the south west we looked across the fjord on the peaks of the western division of the Sondmore Alps and could clearly distinguish our new mountains of last week.

But how impossible is it to convey an idea of all we saw and felt during the heavenly half-hour we spent that summer evening on the airy spire of Slogen. Suffice it to say we were happy, with the perfect and utter mountaineering happiness “born of the long struggle finally ending in victory, though swaying at times in the balance towards defeat”. All things, both evil and good, must however come to an end, and at 9 p.m. we were struck by the thought that our friends below might be getting a little anxious, so it was time we were off. Getting on the glacier which lies on the north side of Slogen we had some fine standing glissades, which gave us so much assistance that the 5,000 feet it had taken over 11 hours to climb were disposed of in one-and-a-quarter. The road in Norangsdal was reached at 10.20, and the Hotel Union at I0.35 p.m., in spite of halts on the way down to admire the magnificent sunset behind the mountain ridge called Saksa, or ‘The Scissors’

Our reception at Öie was so public and cordial that, as modest men, we were grateful for the gathering dusk, the more especially as certain essential garments had suffered considerably during our long wrestle with the rocks. We sat down at 11 p.m. to the excellent dinner provided, even at this late hour, by Frau Stub. Our day on the seaward face of Slogen will ever remain the brightest memory of that gloriously fine fortnight we spent in the Sondmore Alps of ‘Gamle Norge’.

[1] “It seemed to me as though that I did glide,

Not upon water, but in thinnest air

Boundless and measureless as is the ether rare,

Where, from Time’s earliest to latest tide

Amidst Eternity our old Earth rolls.”