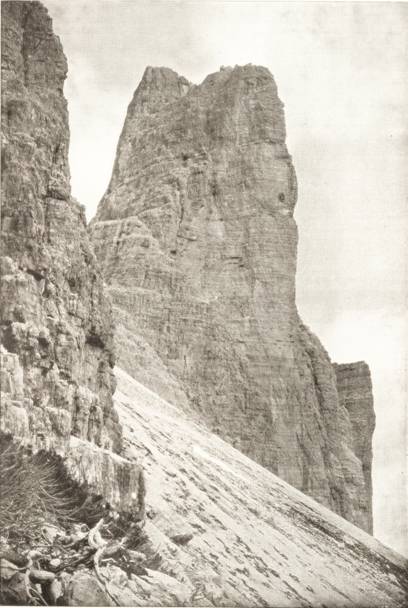

The Kleine Zinne From Cortina

By L. S. Calvert

In July 1899, two of us, sitting on the steps of a jetty beside the Thames, discussed routes and plans for our summer holiday a fortnight hence. On either side rose blocks of dingy warehouses; the heat was stifling in the streets above; the perfume not of Araby the blest.

“Hic in reducta valle Caniculae Vitabis aestus:”

Beyond these sombre walls and muddy waters arose a vision of sunny peaks and clear streams.

Changes are lightsome. This was to be new country – Cortina and the Dolomites, instead of Switzerland. In due course then my wife and myself on the front seat of the royal mail started for the eighteen mile drive from Toblach to Cortina – a drive since familiar, but of undiminished charm; past the little lake embedded in greenery, till Cristallo with the Durren See comes in sight; then on either hand a succession of Dolomite peaks. There is little if any snow on them in August; they have a wealth of colour all their own – jewels in an emerald setting. The road winds round, and below lies Cortina where our two friends await us.

A clear three weeks in hand relieves us from the necessity of an early start and permits of an “Übermorgens Arbeit.” The Dolomite peaks too, appeal to another frailty. No midnight starts are involved. Dinner and breakfast with mutual advantage are less intimately acquainted. Our earliest start was for Popena, at 2 o’clock, the latest at 6.30 a.m. The luxurious huts of the Italian Alpine Club allow one to start even later.

After sixteen days of rock-climbing, beginning with Croda da Lago and relieved by a run down to Venice, our friends’ visit came to an end, and we regretfully saw them off in the early morning.

Left alone with four days’ unexpired leave, the demon of unrest turned my thoughts to the S. face of Col Rosa. Zachariah Pompanin was reported to be quite first rate on rocks and in chimneys; so securing his services, and those of Guiseppe Menardi, we started next morning at 4.0, and had a very sporting time up long chimneys and on traverses. Zachariah maintained his reputation; his acrobatic feats were successful and picturesque. As an understudy I might have done better, but we reached the top at 9.30.

Whilst enjoying that rest which our labours merited, we cast about for the final climb of the season. Zachariah extolled the virtues of the Kleine Zinne. The three peaks were seen in the distance, as they had been from other summits in the past fortnight, and they had a kind of fascination for me. Is there a personality in peaks, that some attract more than others? Why do the Dom, the Weisshorn and other giants mesmerise and invite us more strongly to explore their fastnesses? It is not that they are more difficult or fashionable. Does the spirit of the mountains more especially reign there? I don’t know; but the three spires of this particular set of peaks had for some days thrown their spell over me, and so before we had got back to Cortina at one o’clock it was settled that the last climb should be the Kleine Zinne.

For reasons, doubtless other than professional, Zachariah thought it wise to take his friend as second guide. The next afternoon, then, the two guides, my wife and I, with the instruments of torture, strolled up to Tre Croce, where she left us, and we pushed on to Misurina, through lovely glades and park-like scenery to the little inn at the end of the lake. After dinner, leaving the two guides, I took a boat, with sculls of a sort, and pulled down to the far end. What a weird scene! Overhead the stars; on the mountains the mysterious light; in the water their dark shadows. The Drei Zinnen look down on the lake, and as the boat turns the whole range of Marmolata, Antelao and Sorapis with gleaming patches of snow close in the scene. What a contrast to the gondolas of Venice a week before. But we must turn in – 9 o’clock, lights out – and at 4.30 a.m. we are well on the way for the attack. A hard frost; the last climb of the season; and one’s legs responding to the demands made on them. At a swinging pace we go through woods; past two crosses, through level pasture; then up rather steep slopes, along a shale path, past the Club hut (a better sleeping place than Misurina) until we come under the peak – the Kleine Zinne. A relative term surely, for it is a huge, straight looking tower; to the casual observer impregnable. The day however is young; the inner man is urgent; the weather perfect; so breakfast and a pipe. Then in half-an-hour we reached the N. side. My impression of the ascent is that it is a zig-zag chimney from bottom to top. The first length is comparatively easy. The second takes off from a little ledge without much hand-hold. Zachariah says the next few yards are schwere. I agree with him; even with the help of the rope style is neglected, and for a few seconds I seem to be practising the breast stroke on a rounded face devoid of knobs; but once in the chimney there is excellent climbing, with firm holds. Then a pause, for a small stone with loud humming cuts through the crown of my hat, and I find it well to crawl into a recess, and examine the damage. There was considerable hemorrhage; but the rocks being good I soon reached the guides at the other end of the rope, when they began to rub the wound with Kummel. It seemed a pity this should be used for outward application only. Another start was made. Sometimes we were on the face, sometimes in the cleft, then over a long smooth slab, and with an easy scramble in a few more seconds we were on the summit – a narrow ridge perched in mid-air.

The view is striking: – the Ortler group and the purple haze over Italy; the Dolomites with peaks close around. Ten minutes rest and a pipe; then down the other side. This is sheer enough, but easier than the ascent. Chimney after chimney. About two-thirds of the way down there is a rather long traverse on a ledge. However, finger hold can be found, and remembering the centre of gravity falls, within the base, one inclines to the solid side. That past, we make pace to the shale and snow below, where klettershoes are exchanged for boots, the axes are picked up, and we run down to Misurina and pay the bill – more appalling than the climb. The guides made themselves comfortable at Tre Croce, and I got down to Cortina at 6.30, in time for dinner.

A novel climb, well worth the effort. As a guide once said of the Matterhorn: “you can glissade einmals,” but this is not essential.