On Camping Out

By Charles Scriven

CAMPING out as an aid to sport or a method of recreation might well be more seriously considered by the Yorkshire Ramblers.

There are no doubt members of the Club who look back with pleasure on weeks under canvas with their regiments by the sea, at Strensall or Aldershot, their pleasure increased by pardonable pride in work well done and duties smartly performed. There are great differences, however, between regimental camp life and that experienced by men who go into camp because they like, or hope to like it. The pleasures they enjoy are different. They probably arise from a sense of well-being, a closer acquaintance with nature, and the complete change in one’s daily life, but their enjoyment will also be enhanced if the inevitable daily work and duties are ungrudgingly undertaken.

Under the most easy conditions there are days of stress and storm as of peace and sunshine. The word camp suggests to the mind the camp fire, the smoking of pipes, the swapping of yarns, and the singing of songs; but it will also remind old hands of bad weather, bad cooking, and bad tempers. Men who camp together must soon become good companions and friends, or disagree more or less violently. They learn more of one another in a week than in years of acquaintanceship. The life is so intimate. Therefore consider well the men you join camp with, their tastes, and their capacity and inclination for work. The freedom of camp life is not entirely absolute. It is only to a less extent hampered by the mutual considerations which govern all communal living. The pleasures of grumbling will surely be indulged in, but they are quite as deep and satisfying if the grumbler can find the right man, and choose the right time and the right thing to grumble about. If these slight indications alarm the reader, he should only go away with men he knows well enough to quarrel with. The writer has had some experience of camps and campers. Fine-weather camps, bad weather camps, men who worked, men who shirked, have fallen to his lot. The result encourages him to go on and to try and persuade others to share his experience.

Although the Editor of the Journal expects a technical article rather than an essay upon the ethics Of Camping, it is not the writer’s intention to go closely into matters of detail. He wishes rather to convey a general idea of the possibilities a camp offers to a city dweller by a brief account of his camp at Appletreewick during’ the last three summers.

The camp was suggested by a week-end spent under canvas at Well four years’ ago. On that occasion, a tent, twelve feet by ten feet, was hired, a stack’ cover borrowed for the floor, and straw to lie on. A kind-hearted inhabitant lent the knives, forks, plates, and other needful equipage. The tent was pitched on a hill overlooking the Vale of Mowbray, with the village of Well nestling in the trees below, and the Hambleton Hills in the distance. The situation was charming, the weather fine, and the writer was enamoured of his experience. A week later at Appletreewick, walking along the right bank of the Wharfe towards the fine ravine near Off Wood, the thought crossed his mind, what a grand place for a summer camp if one could make a level platform on the hillside. The thought was acted upon without delay. The tenant agreed to make the platform at once. The following week a bell-tent and board floor were fortunately bought at an auction, and were with some trouble got up to Appletreewick and pitched upon the desired spot.

It would, perhaps, be well to point out that in pitching a tent it is wise to consider the wind, and it is specially desirable in choosing the site for a more or less permanent camp to notice the prevailing local winds. lt is extremely unpleasant to sit in a room with a smoky chimney, and it is quite as unpleasant in camp when the wind brings back the smoke of your fire upon you or is generally blowing in at your tent door. Trenching is another necessary precaution, and it is wise to insist that all rubbish, tins, broken glass, etc., should be buried. At Appletreewick an ash pit has been provided.

The curiosity of cattle is well known. They were rather a nuisance, and created an amusing incident. One night, when all were sound asleep, a terrific yell startled everyone into the fearfulness of sudden awakening. “Help! the hair is being pulled off my head.” First aid was followed by investigation. It appeared the victim was sleeping close to the curtain of the tent and his protruding hair aroused either the curiosity or cupidity of a grazing cow. Fortunately, we were in time to save both hair and cow. My landlord took an active interest in the camp, and rendered every possible assistance. He was good enough in the following spring to enlarge the ground and surround it with a post and wire fence. This second year, an oblong tent, 12 feet by 10 feet, with board floor, was added and used mainly for sleeping in. It was also most comfortable for eating or sitting in during bad weather, and has passed through many severe tests satisfactorily An iron tripod for the camp fire, enamelled pots, pans, jugs and basins, and knives, forks, and spoons, lamps, additional blankets and mattress covers, and hampers to pack them in, were also bought and the camp became almost luxurious. A word in season about lamps would be well. An unfortunate experience in the regimental camp at Whitby, when the oil lamp in my tent exploded and burnt part of my kit, decided me to only admit candle lamps, and they answered very well.

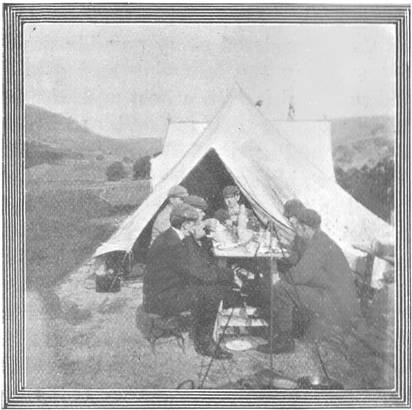

The third year, another bell-tent with board floor appeared in the camp, making three in all. This tent had been used for sleeping out in the orchard at home during hot weather-a proceeding which at first considerably astonished my neighbours, provoked the jeers and gibes of my friends, and aroused the suspicion of the policeman. Camp chairs were a source of some trouble and expense, but a suitable chair was found at last. It is made entirely of wood. When not in use it can be folded flat, is easily stored away, and does not suffer from exposure to the weather. Water is one of the prime necessities, and as there is none quite close an iron tank on wheels was provided to hold all required for washing purposes. Drinking-water has to be fetched from a spring near the river. The spring has never failed to give all the beautiful, cool, clear water required. Water suggests fire. At first wood was procured, more or less casually, but later from Hartlington Saw Mill. Most men seem to have an enthusiasm for chopping and sawing wood. Alas! it is generally evanescent and quickly evaporates in perspiration. Yet it is grand exercise and a great provoker of appetite when practised in the open air. Butter, eggs, milk, bread, sugar, etc., were always obtainable from the village, but meat and the many little luxuries dear to the hearts of most Ramblers were taken from town. For beds and pillows, bags made of linen tick were provided and filled with straw.

Having thus sketched some of the details, the picture can be best filled in by a brief account of life in camp. Perhaps a confession, that in later more luxurious days my landlord pitches the tents on Saturday ready for our coming, to preface the story, will, by its frankness, disarm the criticisms of the stern, self-reliant Rambler who talks of “Whymper” tents pitched in inaccessible rocky fastnesses, of stony beds and stone pillows, and howling tempests, who, in the midst of nature’s horrid turmoil is composed enough to take snapshots of swaying tent and struggling men, or to produce realistic sketches of his I thrilling experiences. Peace and indulgence for his friends and himself to dwell in their Capua, and permission to reverently recount the tales that Rambler has told us over the evening pipe is all the writer asks.

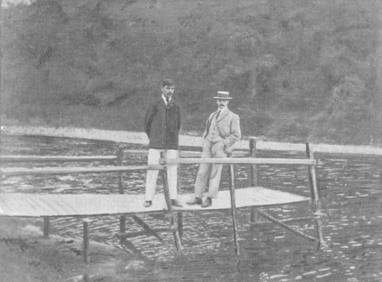

Finding the tents pitched, my first care is to hoist the flags to show one is in residence. Then the chores are arranged. Water is fetched; the fire started; mattresses and pillows filled and blankets aired; supper is got ready and eaten; and all settle down round the camp fire to smoke, to talk, and sing. How good it all is! The river murmuring below, the wind whispering through the trees, the darkness slowly creeping over the valley, and the stars shining out one by one until full night has come and we turn in. Sleep does not, however, always come easily the first night. There are strange noises, and often the cry of the corncrake keeps one waking. Insomnia, however, has no real place in camp life and soon vanishes. After night the dawn, and after dawn the day calls us to be up and doing. People who have never spent a night out can hardly realise the joy and glory of a fine English summer morning. Its exquisite freshness, the singing birds, the dewy grass, the opening flowers, the glittering river, make one resolve never to miss it. A resolution, alas, so easily made, so badly kept! First we bathe. The Wharfe below the camp widens out into a large pool over 200 feet wide, with deep water in the middle, and a firm sandy bottom sloping gently into it on our side. Swimming suggested diving, so procuring some spars and chesses from the Saw Mills, an engineering friend and I erected a diving platform, which is greatly appreciated by the campers and the boys of the village. The platform has, of course, to be removed at the end of the summer, or the autumn floods would make short work of it.

An occurrence, both unpleasant and amusing, happened one morning. My Irish terrier had accompanied me to the river, and I called upon him to follow me into the water. Unfortunately, when half way across he seemed to lose heart and tried to climb upon my back. I turned over quickly and caught him with my left hand, and turned him to the bank. He had managed to scratch me severely, and the marks of his claws remained on my back for some time after. One of the bathers – an indifferent swimmer – was so amused with this little pantomime that he laughed heartily. Unfortunately, he had forgotten he was out of his depth, and as the breath went out of him he disappeared, and when he again reached the surface considerably flustered and with more water in him than he cared for, he was very glad to make the best of his way waterlogged to shallow water. After all, “he laughs best who laughs last.”

After bathing, the tents are turned out and breakfast prepared, eaten and cleared away, and the day is before us.

As many men have camped with me, many and varied have been the ways in which they have spent the days. Some have fished, and camp fare has been the pleasanter for fresh trout and watercress. Many have walked up Simon’s Seat, famous for the bleaberries which grow most plentifully at the base of the summit-rocks, upon which some of us have climbed. Others have traversed Troller’s Gill and visited Hell Hole, whose name recalls the discomfort of its narrow ways, sharp rocks, and the unpleasantly hard work of its first descent. There are many other excursions within easy distance. Wharfedale is so familiar to Ramblers that one need hardly recall its riverside paths, its woods with their ferns and flowers, and its quaint villages, but may safely leave them to imagine for themselves, how not one, but many happy days can be spent from such a base as the camp. As an aid to a form of sport specially favoured by the Club, namely, pot-holing, camping out is specially valuable, and I was fortunately able to lend the necessary equipment for the party who descended Alum Pot in 1900. In many cases the Pot-Holes to be explored are some distance from the nearest possible accommodation. It is notorious that no day is too long for the exploration of a first-class Pot. The advantages of camping on the spot and getting to work in the early morning are sufficiently obvious to need no recounting. It is equally advantageous to climbers. Even cyclists are taking it up seriously, and one reads of men who are enthusiastic enough to carry on their machines a tent and the cooking and sleeping necessaries.

My repeated advice to you is, if you decide to camp, be prepared to take your share of the inevitable work, and consider the men you camp with. You may then rely upon enjoying present pleasures beyond expectation, and you will provide yourself with more permanent pleasures – the pleasures of memory.