The Ancient Kingdom Of Mourne

By Lewis Moore

The kingdom of Mourne is a small tract of mountain country about 15 miles by 12, occupying the southern and eastern corner of County Down. It was seized or settled in the 12th century by immigrants from Monaghan. These people of the tribe of the MacMahons, who came from Cre Mourne (Crioch Mughdoorna), thc country of the descendants of Mughdorn, son of Colla Meann, brother ,of Colla Nais, King of Ireland A.D. 323-326, were called the Mughdoorna, :mtl time has clipped the name they gave the country until it has become Mourne. The Anglo-Normans secured possession of the district shortly after their arrival, and their two chief strongholds were Dundrum Castle in the north and Green Castle in the south. But their occupation was not altogether peaceful. The mountain fastnesses were a sure refuge to the restless Irish, who several times cut up their forces and destroyed their castles. The Mourne mountains were called Beanna Boirche (Banna Borka), the mountains of Boirche, or literally the horns of Boirche, Ross Ruddy-yellow’s cowherd. Ross was King of Ulster A.D. 248, and this was his herdsman’s seat the Benn, and equally would he herd every cow from Dunseverick to the Boyne, and no beast of them would graze a bit in excess of another. So thence is Benn Boirche, Boirche’s Peak, as said (the poet):-

“Boirche, the famous cowherd,

Who belonged to very mighty Ross the Red:

The peak was the soft seat of the herdsman,

Who was not weak against sadness.”

I quote from a curious 12th century work and might explain that Dunscverick is a castle on the coast of Antrim near the Giant’s Causeway, and the Boyne is a good many miles south of Mourne, so that Boirchc was evidently a very superior person indeed, whose mobility probably exceeded even that of a Boer commando.

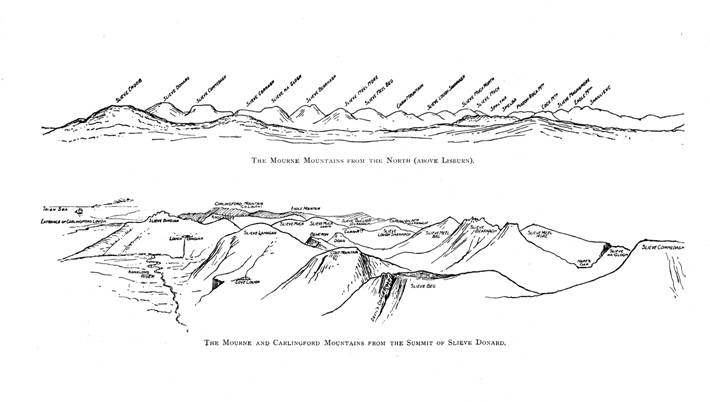

The geological memoir to the Ordnance Survey, a most interesting pamphlet even to a layman, thus describes the Mourne mountains:- “The mountains of Mourne, extending about 15 miles from east to west, form a connected group of elevations, culminating in Slieve Donard, which rises to a height of 2,796 feet at its eastern extremity. Several of the other elevations, lying in the eastern part of the group, fall but little short of the height attained by Slieve Donard. Thus Slieve Bingian attains an elevation of 2,449 feet; Slieve Bearnagh, 2,394 feet; Slieve Lamagan, 2,306 feet; and Slieve Meel More, 2,237 feet; while, in the western portion, Eagle Mountain has an elevation of 2,084 feet. Several of these elevations are isolated and dome-shaped, Slieve Donard being a conspicuous example of this form; others are in the form of ridges, some, times rocky and serrated, such as Bingian, Cove Mountain, and Ben Crom. In general, a slope of greater steepness than 45 to 50 is of rare occurrence, except for small descents. Both in its physical features and geological structure the district bears a striking resemblance to the Island of Arran.”

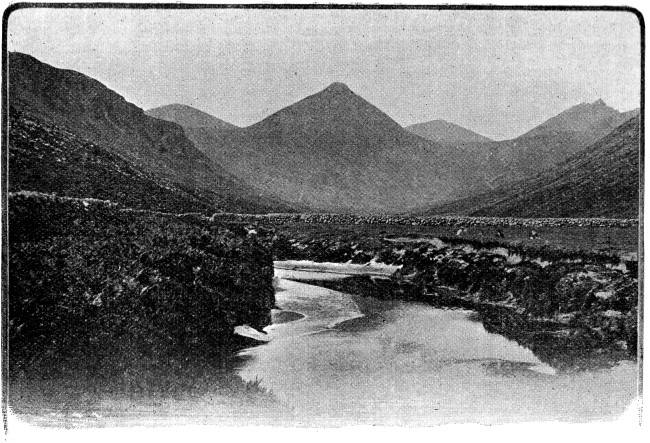

The mountains form a mighty crescent, whose steadfast horns rest silently, here, stony and stern in the sombre firs of Newcastle, there, grassy and gracious in the green oaks of Rostrevor. On its north-west face were massed the great armies of the ice-king. The glacial streams moved over the flatter plains of Iveagh, on their south and south-east march, to be arrested by this little army of mountains. Battalions were heaped on battalions; but the hills stood firm, and the ice-flow, deflected and broken, sought the sea north of east by Slievenaman and the gorges of the Shimna, or fled south down the valleys of Kilbroney, Ghann, and Moygannon, to the fiord of Carlingford.

The ice was, however, only repulsed; as reinforcements poured in the valleys were gradually filled, and higher with each fresh assault it carried some of the outlying lower hills, till at length we find the greater heights, with elevations from 1,900 to 2,200 feet, going under in the struggle. At the higher levels the ice sheet moved in its normal direction, from the north northwest, and it is probable only the highest summits remained above its surface.

The ice has disappeared, slowly, reluctantly, leaving the exposed rocks smooth and striated. Losing here and there as it retreated, trapped by the encircling hills, a straggler, a white weary glacier haunting the dark valleys it may be for centuries. Tardily melting and moving under their loads of drift and débris, the glaciers have built their own monuments out of these very burdens, and left moraines of heaped-up stones to mark the years and the house of their bondage.

This crescent of hills encloses the kingdom like a great wall, and it is traversed by only two roads, one along the coast from Newcastle to Rostrevor, the other across the mountains from Hilltown to Kilkeel.

Newcastle is the northern gate, and is the natural entry for visitors who cross the Irish Channel by any of the routes to Belfast. It is a very beautiful place, and the view of the mountains is distinctly line. Behind the village is Slieve Donard, rising out of the sea quickly to its summit, its flanks clothed by fir trees for 700 feet. To the north-west are Slieve Commedagh and Shans Slieve. The country at their bases is finely wooded, and the colouring of the foliage is always a great feature. Seen in spring, clothed in all the shades of tenderest green, or in summer brilliantly green; with the bright patches of fresh-mown grass land, it is charming, while in autumn it is gloriously brilliant, with its many hues of red and brightest brown. It boasts the possession of a line hotel built by the Co. Down Railway Company, and one of the best golf courses in the United Kingdom. I am told it is a very sporting one with fearful bunkers and the dread hazards of a Matterhorn. The bathing is also good, and, in addition to walks and climbs in the mountains, many charming cycle excursions are possible. One of the best, although the roads are by no means good – in fact, judged from an English standpoint, many miles are execrably bad – is to ride round the mountains. The route is by way of Bryansford, Lord Roden’s seat, to Hilltown and Rostrevor and then back by the coast through Kilkeel and Annalong to Newcastle. It can be done in an afternoon, but it is worth a whole day, and gives many beautiful and interesting views of the mountains.

The actual frontier of Mourne crosses the road some distance out of Newcastle on the shoulder of Donard, and as Newcastle has never been my headquarters in Mourne, I propose to take you some five Irish miles further down the coast. Across the frontier we are in the so-called funny end of this little kingdom. The adjective was applied to the strip of foreshore between this and Annalong, because the people did not earn their living by working but by smuggling and illicit distilling, and spent their spare time in fun and sport, and their earnings in pleasure. Near by is Stropatrick, where, as the old legend relates, St. Patrick making his diocesan visits, in the old style – with staff and shoon – was seized with a great thirst. The holy man thrust his staff into the ground, and there welled up a bubbling spring, which has never ceased to run cool and clear to this day. Its waters are said to have miraculous healing powers if applied before sunrise. The legend goes on to say St. Patrick having quenched , his thirst, douce man, was so refreshed and elated, that he threw his brogues into the township of Ballykeel, seven miles away, where another stream came up, and runs to this day with the name of Brogued.

On the other side of the road is Maggie’s Leap, a deep narrow chasm in the cliff. Opinions are divided about Maggie. Malicious rumour hath it she was a witch; but charity maintains her to have been a pretty Irish girl, with her eggs, on the way to market, who, to escape the kisses of two young men, safely leaped the cleft.

Yet a little distance further is Armour’s Hole, another rift in the rock, where a murder was committed. A father and son set out to Ballaghanary to find a wife for the son, and met with some success. Unfortunately, potheen was freely drunk, and a hitch arose in the negotiations. The man’s father maintained the girl’s dowry to be insufficient, and refused his consent. The son was satisfied; but the father remained obdurate, and they quarrelled on the road home, with the result that the son pitched his avaricious parent into this hole, for which he was duly hanged.

About three-quarters of a mile away, we pass the Jaws of Hell. This hole got its name, in the earlier years of the last century, in a land dispute between two claimants for some farm property here. The unpopular side won, and evicted the occupiers, but the other residents, who were chiefly smugglers and in possession of arms, in turn ejected the new tenants – three men and i a bulldog – one dark night. Two of the men made off to Newcastle in their shirts, the other was, detained by a falling stone, but not killed, and the bulldog died from acute lead poisoning. Nothing daunted, other tenants came forward, and the natives, their patience exhausted, collected their horses, cattle, and donkeys, in the darkness, and drove the poor terrified beasts headlong into this chasm.

The road now crosses what is known as the Bloody Bridge river. Looking down, some 80 feet below us, are the ivy-grown remains of the bridge that carried the old road across the ravine. The place is raggedly picturesque, with its wealth of bracken, bramble, and heather. The mountain stream rippling over its stony bed, in time of flood becomes a raging torrent, leaping its short course from the flanks of Donard to the sea in a succession of roaring cataracts. Across the bridge are the clustered houses of a tiny hamlet, whitewashed cottages with stacks of peat, the inevitable fuchsia, thickly stained with blood-red blossoms, usurping the sovereignty of their hedgerows, and the mountain ash, in the glory of its green livery and scarlet facings, throwing its light shadows across their lintels. The family spends its time according to its age. The parents work, as a rule, hard. The children drive in the cows, tent pigs, or load the donkey creels with wrack on the shore.

The road we are driving on was made in 1845 during the potato famine, as a relief work. At this point it cuts through an old graveyard. When the cutting was opened bones protruded in places, and all the workmen but four gave up work. The day after, curiously enough, a slip took place, burying these four men, of whom two were killed outright, and the survivors died shortly after from injuries and shock.

The ruins among the graves are all that is left of St. Mary’s Abbey. About it are numerous forths, or clusters of old white thorn bushes. These forths are the objects of superstitious regard even in these days. The white thorn is sacred to the “wee-people” or fairies, and though often in the way, and specially adapted for some parts of boat-building, is never used, or disturbed. No fisherman would go to sea in a boat so built; and the peasant farmer believes either he or his cattle would die. When an offence against the white thorn had been committed, and the curse lay upon its perpetrators, it was customary to burn a living chicken as an offering to the “wee-people.”

My informant assures me that there are old people still living who maintain, as they look back through the glamour of the years that are gone, they danced to fairy music under these forths, in the summer twilight of their golden age.

Between St. Mary’s and the Crooked Bridge existed at hotbed of smuggling. The coast was well suited for the work, steep low cliffs grown up with splendid cover, very little if any beach, with deep water up to the rocks. The smugglers could lay their vessels, in calm weather, under the very shadow of the cliffs, and many a cargo of brandy and tobacco was run successfully by the “Ballagh boys.”

It is a long lane that has no turning, and here we are rattling down the hill of Dunmore with Glassdrummond (the green ridge), our destination, before us. If I have made too much of the road, forgive me. It is the great artery of the country. Over its dusty surface are carried all the land-born imports and exports, whether they be tourists or goods and chattels. Along it go the child to school, the youth a-wooing. In tasteful finery the wedding party picks a smiling way through its loose pebbles, or the doleful funeral crawls mournfully over its wet surface. Round about it, naturally, as it slips through the inhabited and cultivated strip of land, ‘twixt sea and mountain, has sprung up tale and legend, history and fable, and though often a tourist’s only vision of Mourne is over its walls and hedges, yet, wittingly or unwittingly, he has had his thumb on the pulse of the Kingdom.

In this little hamlet of Glassdrummond I have spent many happy days. It is always beautiful to me. Rain or shine, as the Yankees say, hot or cold, it is ever kindly Mourne. The Irish are not the English, but different. Different in the charm of their speech, in their happy hospitality, in the picturesqueness of their habit of thought, in the knack they have of making you think what a very fine fellow you are, in spite of that uncomfortable consciousness that won’t be convinced, and that gives one so many unpleasant quarter-hours. I stay in a wooden bungalow, which stands in a small garden on the banks of a mountain stream. The building is somewhat squat, and cannot be called artistic; but it has this merit, it hides itself as much as possible, and its low-pitched roof can hardly be seen anywhere, except from its own garden. I sometimes wonder that more buildings of a similar nature do not exist in this country. Inexpensive to build, comfortable to live in, they are infinitely superior to the proverbial lodgings of our pleasure resorts. No stairs to climb, no back yards, no fellow-lodgers to annoy, no landlady to bully you if you don’t go to bed when you ought. Your bedroom is a little kingdom, self-supporting and independent. Do you wish to go out, you go through the window. Would you eat or drink, you raid the pantry without fear of disturbing your sleeping neighbours. You do absolutely as you like. If you care for breakfast or dinner, you turn up at the appointed time; if you don’t, so much the worse for you; but there is no waiting and no worry. This bungalow is the headquarters of a family; the children sleep in bunks; so do I, and jolly comfortable they are. But save for sleeping and eating, the life is lived absolutely out of doors. What can a man want more? There is no band, no promenade, but there is the music of running water, the ceaseless rustling of the leaves, and for the rest, the pure air and light of heaven, the mountains and the sea.

The Mourne Mountains are, after all, the most important and attractive of the ancient kingdom’s natural charms, and an attempt must be made to see some of the hill summits, among which so many of one’s best holidays have been spent, postponed from day today by varying causes: lack of resolve, other things to do, or perhaps, most of all, by the sweet idleness of the Mourne shore, it is at last accomplished.

The morning is cloudless and breezy, without a suspicion of wet, so stuffing as much cheese and as many biscuits into my pockets as they will hold, I make a solitary start: solid walking failing to tempt the somewhat jaded palates of any of my sporting friends. Scrambling out of the corner of the kitchen garden, it is hot walking that first mile and a half in the shelter of the glen, with a gradual rise of some 700 feet. Clothed with short, sweet grass, embroidered with countless flowers, yellow ladies’ fingers and tormentilla, pale lilac scabious, and long stems of globe heath, clustered thick with crimson cups of great size and beauty; with frills and furbelows of graceful bracken; gloriously patched, where its tiny river and the weather have worn holes in its gay apparel, with tufts of purple ling and clumps of yellow gorse, the little valley sorely tempts one to smoke and dream by the glistening stream rippling over its sands and boulders.

Then the thought of coming home empty-handed crosses one’s mind, and the charms of the valley are left for the more stimulating pleasures of the mountain and moorland.

Calling at the most advanced outpost of cultivation for my companion and guide, Skilling, I am fortunate enough to find him at home, fit and willing.

Can I interest you in him, I wonder? A little fair man, 5 feet 5 or 6 high, lean and wiry, the expression of his face, from long habit, unconsciously keen and observant, but with no trace of hardness, his manner kindly, and ‘modest to shyness, he is a typical hill man, reminding one of the photographs one so often sees of other, European guides. He is a noted traveller on his own ground. To see him traverse with a hop, skip, and a jump some of the rough, stony places on the hill sides, or come, with never a stumble, in the same way down a steep slope, with its stones and boulders covered with heather, is a lesson. For years he has herded the flocks in these common grazing lands, until every yard of the ground is familiar. The paths are infinitely better known to him than the lines in his own hands, and if he does not look at the hills from a mountaineering standpoint, taking probably from choice the easier ways, he knows where to find the scarce plants, the quartz crystals, or, most lucky thing of all, the white heather. Though a non-smoker, and a nearly total abstainer, he reverses the common maxim, lives high and thinks plainly with happy results, and you will find him at the end of the day, as he started, cool and grey, like one of his own granite boulders.

Leaving the house, we cross the valley to the Rocky Mountain road. The sight of a big stone on the road side recalls to both of us a day’s shooting a year ago. A stormy, blustering day, we sheltered under this very stone as completely as we could. Our feet we were unable to conceal, so while we ate our lunch to save time, the rain filled our boots with water. The Rocky Mountain has been described to me as the, goldfield of the district. It is deeply scarred with quarries, from which granite of fine texture and quality is obtained, and largely exported to England. Once over the pass between Rocky and Chimney Rock Mountains, we turn northward along the eastern side of the Annalong River Valley. We stop to admire the view, facing our day’s intended Work, the inner ring of the mountains.

In front, between Lamagan to our left, and the Devil’s Coach-road to our right, is the Cove Mountain, with a fine buttress of rock springing out of the valley. Near the bottom of this buttress, and in about the middle of its southern front, is a lofty natural tunnel, which I take this opportunity to describe.

The first step into this tunnel is a little long, and wet by reason of the small stream trickling down it; but this once passed there is no further difficulty. The passage in its lower part is thickly grown with long lush grass, and we were surprised to find some half-dozen very fine foxgloves growing, probably from bird-borne seed, within its shelter. The tunnel has an upward inclination of perhaps 30 degrees, and its higher exit is nearly blocked with big boulders. These boulders look somewhat unsafe, but are tightly jammed, and a very easy scramble brings one to the little man-hole in the left-hand corner of the pile. It is a very tight squeeze for me, and the aggravating absence of foothold, just when a good shove would be useful, lengthens the fun for a minute or two. Once out you find yourself in a cup-shaped hollow, not unlike a Yorkshire pothole. Climbing out of this, a scramble round the corner of a little cliff brings you to the Cove Lough. The Lough is very tiny, and has shrunk greatly in recent years. It is probably a coomb hollowed by ice.

In the meantime we have been steadily going north. I am particularly anxious to see the Devil’s Coach-road, and we propose to turn the flanks of the opposing peaks, by a passage up this gully.

Nearly opposite, we take a diagonal course across the valley, and are quickly at the foot of the fine granite cliffs that guard its entrance. Rising a height of probably 100 feet, these cliffs are, save for the joints one would find in a stone wall, as vertical and smooth as if’ they had been mason-built with plumb and chisel. The gully, at this its lower end, strewn with granite scree and boulders, will be about 12 yards wide, and leads upwards at an angle varying from 40 to 45 degrees, estimated. It is not difficult, but catches my wind a bit, a matter not troubling Skilling, who takes things leisurely, showing one now a rare grass growing at its side, or indicating with his stick the desirability of a traverse. As we get higher it narrows, the boulders disappear, a smooth outcrop of rock splits it up the middle, and passing this on the left, we find ourselves on a steep slope of fine granitic sand. This sand has its peculiarities: it is very hard but inclined to slip, and does not give very good foothold. Following instructions I traverse it, to find myself ingloriously spread-eagled in the middle. Taking things quietly, I am soon moving again in the right direction, and quickly joining Skilling at the top, none the worse, we take five minutes’ rest, and enjoy the magnificent panorama. Opposite are the twin peaks of Slieve Bearnagh, a beautiful mountain, the Castor and Pollux of Mourne, and as the eye follows the valley of the Kilkeel river southward, Slieve Mweel. Beg, Slieve Lough Shannagh, the Carn Mountain, the north and south peaks of Slieve Muck, and Ben Crom stand brown and desolate, but grand and glorious, backed by ridge upon ridge, until Slieve Ban and Slieve Dermot are lost in the haze hovering above the blue waters of Carlingford.

Pushing on, we are soon on the top of the Cove mountain, and keeping along the ridge over the intersecting valley, reach the summit of Larnagan (2,301 feet). Lamagan, on its south-east slopes, is one of the steepest of these hills; but we had approached it from the north, and had no exciting scrambles over the slabs of rock at awkward angles, or up the precipices with which those slopes are scarred.

Sitting on the summit in the sun, it is difficult to realise a glacier sweeping round the mountain base. Without doubt one did so in the prehistoric past, and the deep cutting in which the river flows far below us is waterworn, through a moraine once damming this valley and making a lake whose bed of naked rock-strewn sand still rejects the advances of grass and heather. The little lake at the foot of the southern face is the Blue Lake.

Now, once more, we turn our faces northward, and over the backs of the mountains we have just climbed, reach the pass between the cliffs of the Devil’s Coach-road and Commedagh.

Turning eastward in this pass, we get on to the once famous Brandy Paths. Indebted to their smuggling associations for their name, they were the roads by which, on the backs of sturdy ponies, many a cask of brandy and bale of tobacco found their way into the markets of Hilltown, Rathriland, and Lurgan.

Moving as the smugglers did at night, the journey was not without risk in bad weather. Fights were not unusual. A keg was generally on tap to quench the thirst or stimulate the courage of the drivers. No accident ever seems to have happened on which to found a legend; but Borcha, the ghostly herdsman of Ulster, still gathers and drives his cattle through the moaning night wind, or the creeping fog.

Above us are the Castles of Kivittar, clothing the steep slope like the ruins of a great temple. These castles more resemble pillars, with their clean vertical and horizontal joints. The more weathered ones lose this clearness of joint, and gradually assume a spheroidal form, until at last they become the familiar rounded blocks lying in the scree below.

After wandering among them a few minutes we climb Slieve Commedagh, the second peak of the range (2,512 feet), by its western shoulder. This mountain is also known as the Meadow Mountain, on account of its greenness, and the sweetness of its pasture. My guide, more shepherd than mountaineer, spoke tenderly of it as a “kindly mountain.” It gives, perhaps, the finest view in the district. It commands the valleys of the Kilkeel and Annalong rivers, in it meet the two converging lines of hills, and it looks south and west over the peaks and passes of this brown silent land. North and north-west, over the lesser heights of Shanslieve, and Luke’s Mountain, across the valley of the Shimna, are the dark green woods of Tollymore and Bryansford, the waters of Lough Island Reary, Hunshigo, and Castlewellan Lakes, and away in the distance the granite mass of Slieve Croob. The fertile plains of Lecale, thickly dotted with house and cabin, the spotless whitewash and roofs of blue-grey slate or brown thatch relieving the gold and green of their patches of corn and eddish, complete the landscape. Eastward is the dome of Donard, and below us the great ravine of the Glen River, with the crags and precipices of the Eagle Rock. It is only four o’clock, so a “wee cut” is proposed to the top of Donard.

Leaving the summit in a south-easterly direction, we jog-trot to the Col at the head of the ravine. Baddeley compares this ravine with Glen Sannox in Arran, and Glen Sligachan in Skye. The col is about 1,000 feet below the summit of Donard, and once over it we take a north-east slant across the granite-littered slopes.

I must confess the sun and my guide, between them, make me very hot. Skilling, with his long ash stick across his back to expand the lungs, and his cool canny face, had plenty of breath for conversation. He looks round and sees me flushed and blowing, turns a bit out of his way, and stops before a spring of most delicious water, gushing out, forceful and bright, beneath a granite boulder. A drink, three minutes breathing time, and the assurance of “only another ten minutes to the top,” send me forward with renewed vigour after the little man, who moves over the hillside like “Sam’le Tamson,” as if he could not help it, and would never stop. There is nothing, after all, like plodding perseverance, and finally we stand on the summit, our fifth to-day.

The bay beneath us, with its beautiful sweeping curve, and calm waters breaking with white-tipped waves on the golden sands, is green in its shallows and in its deeper places blue; part of the blue sea stretching eastward as far as the eye can see, with the purple hills of Manxland alone breaking its surface 50 miles away. Over the spires and roofs of Newcastle, nearly 3,000 feet below, my guide points out the castles of Dundrum.and Ardglass, Downpatrick, Strangford Lough, and the Narrows of Strangford and Portaferry, and far away in the distance the Cave Hill beyond Belfast. Reluctantly leaving it all behind us we make for home, and in 50 minutes are on the threshold of Skilling’s cottage. I required no pressing to accept his invitation to enter. The good wife came forward with a hospitable smile, that augured well for afternoon tea, and sent us through the kitchen – with its peat fire clear and red, the incense sweetening the house – into the parlour beyond. These open hearths are the sacred altars of domestic husbandry, the sanctum sanctorum; the glow of the sacrificial peat is the soul of the house, and something more than mortal. This one has been burning continuously for 30 years, and there are fires in the country side that have entered their second century. Mrs. Skilling’s parlour is pleasantly cool. Its low open ceiling, white walls, and bright pictures from the illustrated journals are a pleasant relief after a day in the sunshine; and through the window, with its small panes of glass, one gets little peeps of the world of rock and heather without. The kettle was on the fire when we arrived, and tea is ready almost at once. It was delicious.

I have attempted to describe only one day among many spent on the mountain slopes and summits of Mourne, but I must not conclude without some mention of Slieve Bingian and Slieve Bearnagh, the two most beautiful peaks in the range.

Their beauty is mainly due to the crags upon their summits, locally called Castles. These do not offer much in the way of climbing, although there is a crack on Bearnagh which looks as though it would go. Bingian is a rather extensive mountain, and it has another rocky summit known as the Giant’s Face, upon which I remember making rather an ass of myself. I was tempted to try a very easy looking sort of gully as a way down, and started gaily to descend it. It was a rather curious place, formed by an opening between two great granite blocks, with a considerable downward inclination. The sides, nearly smooth, approached so closely together that I had to back or wriggle down without going right to the bottom. I got down all right to a jammed stone that filled the lower end, and then, to my disgust, found it was too far, to drop from the stone to the ground below, and that it was too smooth and undercut to permit me to climb down it. So I had to turn back, and the next ten minutes were very hot and unpleasant. Eventually I got out again minus some skin off my knees, hands, and elbows, and some dignity. The view from the top of Bingian is very fine. You have a wonderful panorama to the south, and in clear weather can see Howth and the distant mountains of Wicklow. Nearer to you are the Carlingford mountains, the bright waters of Carlingford Lough, and the ruins of Greencastle.

Between Slieve Bingian and Slieve Bearnagh is the Happy Valley, along which runs the Kilkeel River. Belfast is completing a great engineering undertaking which will enable her to draw her water supply from Mourne, and the head of the pipe tunnel is in an old moraine in the valley bottom, shown in the accompanying illustration.

Seventy-five years ago Mourne was a wild, barren country, without roads or bridges. Carts were non-existant. Agricultural implements were of the most primitive kind. Reading and writing were unknown to the people. The kingdom was practically isolated and self supporting. Its inhabitants spun their own wool and flax, weaved their own clothes and only bought boots when they could afford luxury. The principal articles of food were oatmeal and potatoes, and the men were proverbial for their fine physique.

Time has changes all this, but superstitions die hard and there still linger in the minds of the people many quaint beliefs in signs and omens.

Their traditional courtesy and hospitality also remain, and the pleasure of hearing them talk is full of charm and interest. The rambler in Mourne should try to know both the place and the people.