The Keswick Brothers’ Climb Scafell

By J. W. Puttrell

“Cave Canem” indeed! rather should the Pompeiian adage be modernised into “Cave Editorem!”

As a humble, albeit loyal, member of the “Y.R.C.,” one scarcely dared refuse the Editor’s invitation, though the last paragraph in the Editorial Notes

of the Club’s Journal, anent the disinclination of the average member to put pen to paper, applies in very truth to the writer. However, it is a pleasant duty to tell how the Keswick Brothers’ Climb on Scafell was accomplished.

Mr. Haskett Smith, in his slight, yet most useful and interesting book, “Climbing in England,” gives high place to the Scafell Crags, west of Mickledore, for their grandeur, both to look at and to climb, and “in consequence,” he says, “the ground has been gone over very closely by climbers of exceptional skill, and climbing of a somewhat desperate character has occasionally been indulged in.” The truth of these remarks is apparent to all who know the locality and the stupendous crags referred to. There are, however, even yet, in my opinion, openings and opportunities there sufficient to satisfy the most desperate of desperadoes in the climbing fraternity. From 1893 until July, 1897, the four noted climbs on these Crags, namely, North Climb, Collier’s Climb, Moss Ghyll, and Deep Ghyll, held indisputably the “right of way” to the summit level, although many and varied were the assaults made to force a new route. It may not be out of place here to briefly detail the story of an attempt made by a party of four in July, 1896, which yielded fruit the following year.

After a few scrambles on Dow Crag (Coniston) and elsewhere, the writer with a friend, set out for ” pastures new,” to wit, Scafell, and as we looked from a distance at its great north face I said to my friend, “Carter, surely yon front will go?”‘ He gave me to understand, however, that his opinion was quite the reverse. This negative reply really acted as a tonic, and made me doubly determined to overcome the difficulties of an ascent. Nothing further was said for a time, but as we neared the Crags we espied two tourists, apparently climbers, approaching us. Ever ready to cultivate new friendships, we made it our pleasure to exchange greetings, finally inquiring of each other as to our respective programmes for the day. “We have nothing particular on,” said our new acquaintance, Mr. H. Walker, of Whitehaven, who, with his companion, Mr. Gare, had recently returned from the Alps, “so we will follow you.” “All right, come along,” said I, “let us find a way up the Crags here. Are you game?” The cheery response came, “We are triers, anyway.” The writer having accepted the responsibility of leadership, and roping operations being complete, we at once began ‘breaking ground,’ using the Rake’s Progress, the natural terrace along the base of the Crags, from which to commence the attack.

After several desperate and futile attempts to make even a start, a rocky ledge was luckily found above the ‘Progress’ some 24 feet west of what we afterwards learnt was the foot of Collier’s Climb. To the end of this ledge we crawled and climbed. Here we were brought face-on to the second longest of the numerous inclined cracks which are so striking a feature in the Crags. This crack opens out at its broadest here, being at the very least 18 feet wide, and is practically useless as a means of ascent owing to its clean-cut, steeply-slanting walls. Apparently the only alternative to an undignified retreat was for the leader to swing out and up on his arms to the left, and trust to luck for footholds on the wall face. This exciting operation over, and the next 30 or 40 feet safely climbed, the leader arrived at the grassy platform called Collier’s Ledge, connecting our crack with the top of the lower half of Collier’s Climb, several yards away to the left, The remainder of the party followed with tolerable ease. We here came across the late Mr. O. G. Jones’ card, with the record of his descent inscribed thereon. I little thought at the time it would be my privilege during the ensuing brief two or three years to rank him as one of the closest of friends. The route up the face directly from the Moss Ghyll end of the ledge, appeared to the party far from inviting, especially the take-off from this platform. So after careful consideration, and feeling fully conscious of our weakness in attack, we deemed it advisable to turn left and give our attention to the upper part of Collier’s Climb, this to us appearing to be the easiest and most natural way. There were, perhaps, a few soul stirring events en route which one might record, but over these the veil of secrecy shall be drawn. Sufficient is it to mention that we duly arrived at the top, thus successfully completing our first encounter with Scafell Crags. Mention should be made of the able way Mr. Walker seconded the leader’s efforts throughout.

Click on the list items below to highlight the route

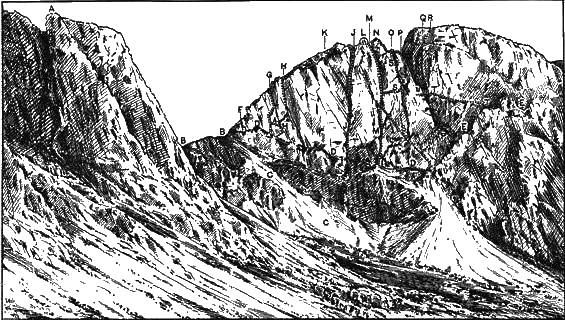

| A – Pulpit Rock (Pike’s Crag). BB – CC – DDD – EE – G – ? – |

L – Pisgah . MM – Steep Ghyll . N – Scafell Pinnacle . n – Haskett Smith’s First Route up Pinnacle . O – Low Man on Pinnacle . P – Deep Ghyll . Q – Great Chimney (Blake’s) . R – Robinson’s Chimney . SSS – Pinnacle Climb . s – Slingsby’s Chimney . TT – Grass Traverse, From Lord’s Rake into Deep Ghyll . U – Hopkinson’s Cairn . |

Gradually the news spread through Lake District climbing circles that new ground had been broken on these Crags below Collier’s Ledge. The first, perhaps, to hear of this were the brothers George and Ashley Abraham, of Keswick, and they naturally wished to know more about the affair. At the time, however, the writer was unaware that anything out of the ordinary had been accomplished, and replied to their queries accordingly. The Abrahams thinking otherwise, desired an early opportunity of visiting the spot with the writer, as they thought there was ‘something in it.’ They rightly surmised, as later events proved, that if the first 30 or 40 feet of this new route were feasible-and we had certainly proved it to be-the remaining 250 or so feet above would ‘go’ also.

It was not, however, until July 12th, 1897, that the matter was put to the test. Eleven a.m. was the hour and Sty Head Tarn the place mutually agreed upon as our rendezvous, and to the minute, be it said, both parties made their appearance, despite the fact that Keswick and Dungeon Ghyll were the respective starting points. This punctuality appeared to us a good omen of our coming success. As a ‘prelude’ we made tracks for the Central Gully on Great End, which climb afforded us some finger-exercise. Near the top we gave the “happy despatch” to our lunch-a conglomerate, if not dangerous mixture-of meat pies, plum tarts, and the ever acceptable, always eatable, Carlsbad plums. This important affair over it did not take us long to reach Mickledore, viá the Ordnance Cairn on Scafell Pike. Before making our way along the Rake’s Progress we carefully scanned the face of the Crags from Mickledore, and discussed our intended new route to the sky line.

Arriving at the foot of our climb, we promptly roped in the following order-George Abraham, Ashley, and the writer. Being eager for the fray, we quickly ascended the first 35 or 40 feet, our leader conquering the difficulties in fine style. This brought us to Collier’s Ledge, the most westerly point reached by the party of the previous year. We anticipated meeting difficulties hereabouts, and certainly were not disappointed, for we found it required some degree of nerve to leave the spacious ledge and tackle the small crack running up the precipitous face of rock above. Trouble we certainly had, but it was trouble which, perforce, must and did yield to the cautious skill of our leader. After this, first by a series of sloping grass patches, then by interesting ledges of rock, we traversed along the face in a generally rising zigzag fashion towards the right, and arrived on the top of an upright oblong pinnacle of rock, where we erected a small cairn over a card recording the event. In order, however, to more clearly indicate the spot from below, we tied a white handkerchief to a stone, allowing the ends to flap in the breeze. Believing that the main difficulties of the climb had been overcome, “half time” was now called and promptly responded to.

The few minutes of leisure were spent in taking stock of the scenery round and about us; rock scenery which, for grandeur, is probably unequalled on any other part of Scafell. One should not forget to mention the impromptu concert arranged on the spot. We certainly made the “hills resound with song,” perhaps more loud than sweet. It gave rise to the following incident. During a brief break in our revelry we were startled to hear voices from across the screes calling out, “Where are you? Do you require help? Can we do anything for you?” We gazed and wondered, and then stared at each other. “Who are those kind inquiring friends over yonder,” remarked one, “who evidently imagine we are stranded and require assistance?” Another took upon himself the responsibility of answering the strangers, and jokingly replied, “Yes; bring us a cup of tea!” Our would-be friends at this, probably realising the situation, turned tail towards Eskdale, we bidding them “Good-bye” as they departed.

“Time” having been called, we recommenced the ascent over good ground, bearing still more to the right, until the long and prominent crack half way between Mickledore and Moss Ghyll was reached. We were now about half way up the crags, and our obvious further course was to leave the face and make use of the crack for the grande finale. The great rock chimney which we entered, and which my companions did me the honour of naming the “Puttrell Chimney,” needed care and finesse of touch – especially on the leader’s part – to make progress possible without damaging the parietals of those immediately beneath, but it provided a splendid finish to a splendid climb.

A good variation for the last 120 feet, and one which avoids all risk of falling stones, may be made after leaving the chimney part, by keeping to the right (looking up) of the bed of the gully, and hugging the right wall closely until the summit level of the crags is reached. This adds a very interesting though not easy bit of climbing, and was made upon the occasion of the second ascent the following Christmas, when Mr. O. G. Jones was one of the party. In these few paragraphs l have given an account of the opening up of the latest route to the summit of Scafell Crags. When, and where, the next one will be found the writer cares not to prophesy. Suffice it to say, it will certainly be a feather in the climbing cap of whoever brings it off.