Dents Des Bouquetins Central Peak By The E. Face

By The Rev. L. S. Calvert

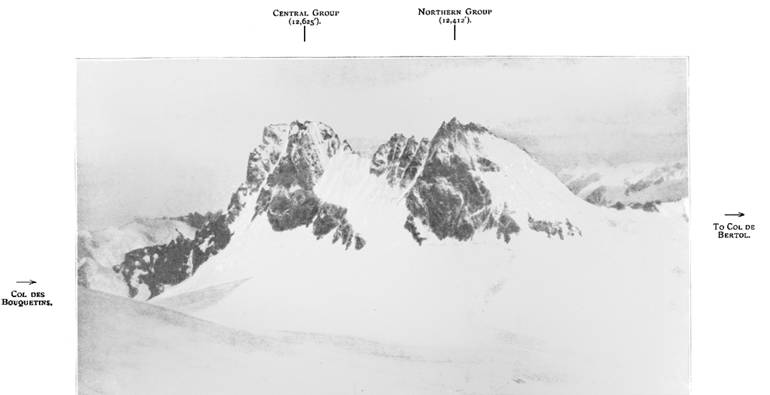

“This wall of peaks may be conveniently divided into three parts,” remarks the Climbers’ Guide!

Somehow this division of things material seems not unfamiliar. A vision of dreamy repose on a warm Sunday afternoon rises before us when we recall early days. Feelings of an opposite nature occur when the triple division of Gaul was explained sub ferula . But to business! Our party, that is the climbing section, at Arolla may also be conveniently divided into three parts, of which, so far as this expedition is concerned, two remained at the base of operations, the third being despatched to feel the enemy’s pulse.

It was the summer of 1897. Loyalty at home in the air: everywhere and everybody en fête. A week’s volunteer camp in Scarborough prior to starting for the Alps had put the coping stone on to the patriotic edifice. We had entertained the Colonial troops right royally; battalion had vied with battalion in honouring the occasion. But alas! Nemesis came, the fly in the pot of ointment, to all these rejoicings. Paucity of breath was the obvious penalty for indiscretion, of which truth the first climb gave internal evidence. There was no chamois-like skipping over boulders and moraine, it was puff and dart to the first stream handy. An unsympathetic allusion to this physical infirmity was, in the end, responsible for the subject of the present paper.

Ten days on the Arolla peaks improved matters, then there came heavy snow. The Za, Mont Collon, and other surrounding peaks were clad in the garb of innocence – part of which, later in the day, the sun cleared off. Tubby, one of the three men on a rope, had damaged his ankle two days previously on the central peak of the Aiguilles Rouges, Withers had only recently come out and desired a few days’ more training, so it was arranged for me to take the guides an expedition. The atmosphere and surroundings of the guides’ room were thought to be detrimental to the morale of our two men, Adolphe Andenmatten and Elias Burgener, of Saas. The self-abnegation of the two aforesaid was touching and obvious. The next thing was to decide upon the peak.

Suggestions were discarded. In the smoke-room was kept a wonderful manuscript guide-book of the district by Mr. Larden. In looking through this my eye caught a foot-note by someone who had made an ascent as follows:- “I think this the most difficult of the excursions from here.” There was an element of attraction in these words which induced me to read the description. It was an ascent of the middle peak of the Dents des Bouquetins. Every man gets his chance some time – here was mine to wipe out the slur on camp life in general. Dents des Bouquetins it shall be. The guides were interviewed, and fell at once to the proposal; the other two were not so sanguine. So far good. After dinner, details were discussed, and here the enervating atmosphere of the guides’ room was apparent. Adolphe and Elias were less keen, not to say doubtful, of success. The Arolla guides, for some reason, had assured them it could not be done on account of the fresh snow, but an appeal to their armour propre had the desired effect, and provisioning then took place.

The summons came at 1 a.m., and going into the dining room I found five other men bent on storming the Aiguilles Rouges – Messrs. Compton, Collier, Valentine-Richards, Brushfield, and Owen. There was a good deal of pleasant chaff about sportsman-like attempts when my little plan was unfolded; it was asserted that one man and two guides could go anywhere, and replied to that two men and two guides could go nowhere. Good fellows all of them, and with the true bonhomie of the mountains – and there is nothing like it. The merry party, with whispered bon voyage , stepped out into the moonlight – they up the mountain for the Rouges, we down to the moraine by the side of the Arolla glacier en route for the Col de Bertol and the Bouquetins.

In order to warm the proceedings up a little, I asked the usual “What do you think of the weather?” Oh! it was going to be bad. It being about the most faultlessly perfect morning it has been my lot to experience, this reply indicated that the mercury in the guides’ barometer needed raising – raised accordingly. Little by little the depressing influence of the salle des guides was evaporating like a mist before the November sun. Allusions to the reputation of Saas Thal men tore away any latent shreds of doubt, and as the moon began to wane and the day to spring, life came to the party and all looked hopeful. But an hour before, as I looked back at the Kurhaus nestling in the pines, bathed in moonlight, and thought of my sleeping companions snugly tucked up under its roof, ” O! terque quaterque beati,” I exclaimed.

Now that is all over – the pace improves – it is distinctly warm. I am carrying a camera. Adolphe says either leave the machinen or peak. In a spirit of conciliation the machinen is temporarily entombed. The steep zig-zag towards the foot of the Col seems easier in the early morning, and we are at the bottom of the moraine in no time. Here five minutes must be spent in gazing on the most glorious of morning effects, almost unearthly in its beauty. The moon was just about full, a cloudless sky, the morning star itself like a moon. The great white Collon, the Pigne, and all the glorious array to left and right were bathed in the soft, sheeny, mysterious light which one can see but not describe. Then, silently, imperceptibly, a deep violet colour steals over the sky which shades off to purple, a blush rose light strikes Mont Collon, and passes over the circle of mountains, then a golden flash and day has come.

Pounding away up the slopes of the Col de Bertol – which the weather of the two previous days had made very bad going, the crust being not strong enough to bear – with much floundering we reached the Col at 5.55. A few minutes to explore and we started across the long snow-fields to the right. This snow was perfect; hard and sparkling in the brilliant sunshine like a held covered with diamonds. Passing round the north peak, the pace still improving in the warm sunshine, we came to a point at the foot of the eastern face which was immediately below what appeared to be the highest peak, and facing midway between the Dent Blanche and the Matterhorn.

Here we unlimber on the snow, and get the breakfast ready – not quite a banquet, but selected for the special tastes of the three by Tubby, that prince of caterers. How I wish he were here! There is all the pleasurable uncertainty of the unknown, and we discuss possible routes between mouthfuls. Which is the highest peak? We are too near to decide the point; all look high enough to satisfy the greatest climbing gourmand.

Adolphe suddenly lights up after exploring fore and aft for a short time. “‘There is the Spitze,” he says, “and we can do it – straight up here.” Waistcoats, sacks, provisions, and all impedimenta are left on the snow. The rope is adjusted and the storming begins. Past a hanging glacier on the right, across a narrow steep couloir, where the fresh snow when disturbed comes hissing down, then bearing to the right until the Matterhorn was immediately in the rear, Adolphe led straight up the face to – what appeared from below – the true summit. No hesitation now – the instinct of the guide was unerring – he stood the god of the mountains revealed. There was good foot and hand hold; for two hours and a half it was real climbing, and we gained the top at 9.30, only to find it was not the top, and separated from us by a deep depression rose the real central peak. “We are done, Adolphe,” I said. “Oh, nein!” he exclaimed, and letting me down part of the tower we all got safely to the bottom and commenced the final ascent. This was not so easy, as the rocks sloped the wrong way; but with this exception, and a little trouble from the fresh snow, there was no serious difficulty, and at 9.50 we stood on the highest peak of the Bouquetins.

Who shall describe that glorious forty minutes? Where are the forebodings of the Arolla men, now? Bravo, Saas Thal! Bravo, my two good men! Elias produces the flask of whisky; the Queen’s health is drunk, and the route christened the Jubilee route. One pipe each as we bask in the sunshine and gaze on the scene too magnificent for words, for are we not in the very centre of all the well-known Alpine giants? The S. Peak, first ascended by Mr. Slingsby, our President, lies below us, the N. Peak behind, and just a few clouds to enhance the effect. A strip of paper with the three names is enclosed, and all-reluctantly the descent is commenced at 10.30. What need to dwell on the return? There was a good deal of “Sind Sie fest?” “Warten Sie,” and involuntary glissades, but no mistakes until the bivouac was reached at 12.50. The fragments were consumed, and a bottle of claret which had been warmed in the sun. A comely sardine, left as a bon bouche, was unfortunately not improved by the sun; a hasty inquest was held upon him, and he was buried in the snow. If you seek his monument, look around. We “took up our carriages,” raced back to the Col de Bertol, disinterred the machinen , and reached the hotel at 4.30. Needless to say the two small photographs which are here given are not mine. I am indebted to my friend, Mr. O. K. Williamson, who made the Bouquetins last August, for his kindness in lending them.

So ends my story of a day never more perfect and never more enjoyed, and never was expedition better led than by my two well-tried friends from Saas Grund.