A New Mountain Aneroid Barometer

(Reprinted from “The Times,” Dec. 17th, 1898. Corrected.)

29, Ludgate Hill, London, December 9th, 1898.

Sir,

Mr. Murray published in 1891 a pamphlet [“How to use the Aneroid Barometer,” 8vo., pp. 61, John Murray, Albemarle St., London], which gave some of the results that had been obtained from numerous comparisons of the Aneroid against the Mercurial Barometer, made by me between the years 1879 and 1890. The earlier of these comparisons were made out of doors up to a height exceeding 20,000 feet; and the later ones were made in the workshop down to a pressure of 14 inches, which is about what one may expect to experience at the height of 20,770 feet above the sea.

These comparisons, or experiments, brought out certain facts. It was found that all aneroids which were tested, ‘upon being submitted to diminution in atmospheric pressure, lost upon the mercurial barometer. It was found, if an aneroid was placed under the receiver of an air-pump (having a mercurial barometer attached, in such a way that one could cause simultaneous reduction in pressure for both barometers), that, although the aneroid might for a moment read truly against the mercurial when pressure was reduced, say, to 20 inches, it would in a very short time read lower than it. It was found that this loss augmented constantly, and that in a single day, under a constant pressure of 20 inches, it might grow to half an inch and even more; and that the loss always continued to augment for several weeks, sometimes so long as seven or eight weeks. The lower the pressure, and the greater the length of time the diminution in pressure was experienced, the greater was the loss in any individual aneroid.

It was found also that aneroids commenced to recover this loss immediately pressure was restored; no matter whether it was restored entirely and suddenly, or gradually and partially, as it is when a traveller is coming down-hill; and that in course of time after return to the level of the sea (or if kept artificially at a pressure of 30 inches or thereabouts) an aneroid might recover all its previous loss, even although it might have experienced very low pressures, and been kept at such pressures for months at a time. Hence, in consequence of the

loss, Travellers or Surveyors may be led to very much exaggerate their altitudes (unless they carry some standard for comparison which will enable them to determine the errors of their aneroids on the spot); and in consequence of the recovery they may be led to believe, on return to the level of the sea, that their aneroids have been working well and truly, although they may have, as a matter of fact, been doing quite the reverse.

The publication of these results led to improvements in the manufacture of the aneroid, and some instruments of the best class which have been constructed in late years show a distinct advance in accuracy; but it is clear, from references which have been made quite recently by Travellers to their aneroids, that there are others which are still a long way from perfection. Mr. E. A. Fitzgerald, for example, says in the “Geographical Journal”, Nov., 1897, “Our aneroids played us some very curious tricks. One of them, on being taken to the height of 19,000 feet, registered 12 inches” – that is to say, it indicated an altitude of about 25,000 feet, and was about 30 per cent. in error. This is several degrees worse than the behaviour of the instrument which was employed by Mr. J. Thomson during his journey in Morocco in 1388, though even his aneroid is said to have made his life a burden to him. One can well believe it did all that was imputed to it; for after Mr. Thomson’s return, when it was tested under the air pump at a pressure corresponding to a little lower than the height of Mont Blanc, upon being kept a week at that pressure, it acquired an error of -1’267 inch, the value of which amount, at the altitude in question, exceeds 2,000 feet.

Manufacturers have endeavoured to tackle the difficulty in one way, and inventors have approached it in another. The former have attempted to abolish the fundamental cause of error, and the latter see that aneroids can be rendered of greater service in the measurement of altitudes by shortening the length of time that they need be exposed to the influence of the atmosphere. The most recent experimental aneroid which has been constructed with this view is the invention of Col. H. Watkin, C.B., Chief Inspector of Position-Finding in the War Department.

In introducing it, Col. Watkin said in effect, though not in these words, “You point out that all aneroids lose upon the mercurial barometer when submitted to a diminution of pressure; that this loss is large when pressure is much diminished; and that the loss continued to augment for several weeks. It is, you say, apparent that the extent of the loss which will occur in any aneroid upon the mercurial barometer on being submitted to a diminution in pressure depends (1) upon the duration of time it may be submitted to diminished pressure, and (2) upon the amount of the diminution in pressure; and that it follows that the errors which will be manifested by any particular aneroid will be greatest when it is submitted to very low pressures for long periods. Accepting this as a correct statement of facts, I propose to construct an aneroid barometer that can be put in action when required, and ‘put out of gear’ or ‘thrown out of action’ when it is not wanted for use; and I propose to construct it in such a way that it shall not be exposed to the influence of variations in atmospheric pressure when it is out of action – in short, that no variations in atmospheric pressure, however large they may be, shall produce any effect upon it except at the time when it is put in action for the purpose of taking a reading.” The following description, supplied by Col. Watkin, explains the manner in which this is done:-

“In order to relieve the strain on the mechanism of the aneroid, and only permit of its being put into action when a reading is required, the lower portion of the vacuum-box, instead of being a fixture (as is the case with ordinary instruments), is allowed to rise. Without entering into details of construction, this is effected generally by attaching to the lower portion of the vacuum-box a screw arrangement, actuated by a fly nut on the outside of the case. Under ordinary conditions this screw is released, and the vacuum-box put out of strain. When a reading is required, the fly nut is screwed up as far as it will go, thus bringing the instrument into the normal condition in which it was graduated.”

At first mention this idea did not appear promising, as it seemed that, however quickly an observation might be made, the aneroid would be losing upon the mercurial all the time that the reading was being taken; that when the aneroid should be thrown out of action, this loss would be shut up; and that when readings should be taken on succeeding occasions the loss which would occur during them would accumulate ; and that this would go on until at length the error would become almost or quite as serious as in an ordinary aneroid. I was, however, very urgently required to give the instrument a fair trial in the field; and after satisfying myself that, when thrown out of action, it was not affected by variations in atmospheric pressure (amongst, other ways by keeping it for six weeks under a receiver in which pressure was maintained constantly at 17 inches), I commenced to compare it against the mercurial barometer in Switzerland in last September, having intentionally refrained from taking a reading for six weeks further, after it was released from the air-pump, in order to obtain confirmation of the opinion that it was, when thrown out of action, actually impervious to the influence of variations in atmospheric pressure.

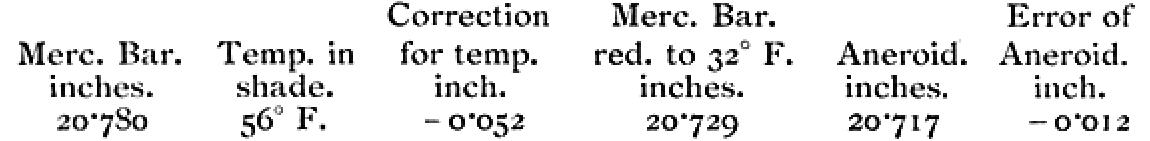

I commenced these comparisons at Zermatt on the 3rd of September [the height of Zermatt, according to the Swiss Federal Survey, is 5,315 feet], and between the 3rd and the 5th took twenty-one readings -that is to say, the aneroid was put in action and was thrown out of action twenty-one times in the above-mentioned period. I was interested to observe whether the accumulation of loss would take place. It did occur, but the total amount was small. The aneroid had a plus error of 0’122 of an inch the first time it was used, and this was reduced to + 0’069 of an inch at the last reading. Thus there was, on an average, a loss of 0’00252 (or

![]()

) of an inch on each occasion that a reading was taken.

On September 9th I carried the barometers to the top of the Gornergrat, but diverged from the way up to the summit of a minor peak called Gugel [S. F. Survey, 8,882 feet]. The error of the aneroid at Zermatt at the last reading was + 0’069 of an inch, and on the top of Gugel it was + 0’057, or

![]()

the difference of level between the stations, it will be seen, was 3,567 feet.

From the top of Gugel I came down for lunch to the hotel called the Riffelhaus [S. F. Survey, 8,429 feet], and there the error of the aneroid was +0’041 of an inch.

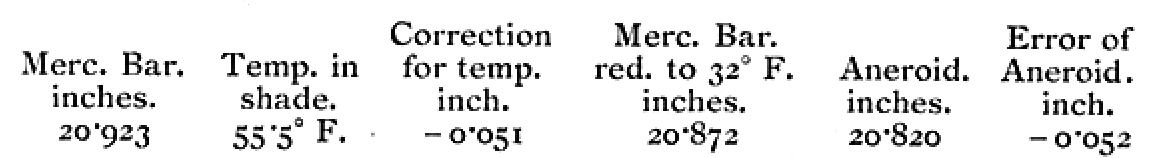

From the Riffelhaus I went to the top of the Gornergrat [S. F. Survey, 10,289 feet], and at 4.20 P.M. the error of the aneroid appeared to be 0’052 of an inch. The readings were:-

I was not satisfied with this comparison. The sun’s rays had been piercingly hot during the ascent, and the mercurial barometer had been unavoidably exposed to them. When set up in the shade, its sensitive, attached thermometer speedily took up the temperature of the air. It fell to 55.5° F., and would not fall lower. But the mercury in the barometer continued to fall long afterwards, because it was not cooled down to the temperature of the air. It is not improbable that the temperature of the mercury in the barometer was as high as 75° F. at the time it was read. Assuming that this was the case; the following would be the Correct comparison:-

On my return to Zermatt, after a descent of 4,974 feet, I was curious to observe what alteration there would be in the error of the aneroid. At the last reading prior to starting it had been + 0’069 of an inch and at the first one taken after the return it was precisely the same! More astonishing than this, the mean of eight readings taken on the four following days (Sept. 10-13) came out + 0’068 of an inch.

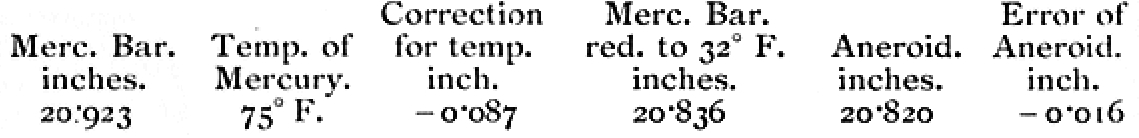

On September 13th I went again to the Gornergrat, and between 12 and 3 read the barometer three times. The following figures show the means of the three readings:

This supported the opinion that the reading on September 9th was taken too soon, and that the temperature indicated by the attached thermometer was lower than the temperature of the mercury in the barometer. The mean of two comparisons at Zermatt after this second visit to the Gornergrat gave, as the error of the aneroid, +0’030 of an inch.

I then went down the Valley of Zermatt, and stopped successively for several days at each of the three villages, Randa, St. Nicholas, and Visp. At Randa [S. F. Survey, 4,741 feet] I made six comparisons on three days, and the mean error of the aneroid came out 0’000. At St. Nicholas [S. F. Survey, 3,678 feet] I took five readings on three days, and the mean error was -0’019 of an inch; and at Visp [S. F. Survey, 2,165 feet] I took three readings on two days, and the mean error was -0’006.

I then thought it would be well to submit the aneroid to a sharp and sudden diminution in pressure, and took the train back to Zermatt to see what would happen through a rise of 3,150 feet, made in 2 hrs. 20 min. At the last reading at Visp the error was -0’002 of an inch, and at Zermatt I found it was +0’011. On return to Visp the mean error of five comparisons made on three days was +0’017 of an inch; at Sierre [S. F. Survey, 1,765 feet] five readings on four days showed a mean error of -0’010, and the mean error of the last two comparisons, made at Geneva [S. F. Survey, 1,227 feet], amounted to -0’030 of an inch. From September 9th to October 17th the aneroid was put in action forty-four times, and its loss upon the mercurial in that time amounted to 0’099 of an inch. A plus error of 0’069 of an inch at Zermatt was changed into a minus one of 0’030 of an inch at Geneva. This was equivalent to a loss of 0’00225 (or

![]()

) of an inch on each occasion that it was used.

The remarkable nature of these figures will be apparent to anyone who has acquaintance with the barometer, and especially to those who have used aneroid barometers in the field. Upon two occasions Col. Watkin’s instrument read so truly against the mercurial that I was unable to detect any discrepancy between the two instruments. At Randa, the mean of six readings gave as a result

no

error. Stress need not be laid upon these happy agreements. It is more to the purpose to draw attention to column G in the following table. If the eye is run down that column, and neglects the hundredths and thousandths of an inch, it will be seen that it reads 0’0 from first to last! Better results might have been attained, and I believe would have been attained, if the readings had been taken with greater rapidity. Attention must be paid to two points when employing this instrument. The first is to keep it constantly shut off from the influence of the atmosphere, except at the times when readings are to be taken; and the second is to take the readings as quickly as possible.

Finally, I feel confident that, in the hands of those who will give the requisite attention, extraordinary results may be obtained from Watkin’s Mountain Aneroid in observations made for altitude, and in determining differences of level.

The comparisons were made against a Mountain Mercurial Barometer, Fortin -principle, which was graduated to read on the vernier to

![]()

of an inch, and by estimation could be read to

![]()

. Before starting in July, this barometer was compared against its Maker’s Standard and it was found to have no error. On return in October it was again examined and compared, and it was found that it had not taken in any air.

The aneroid which was observed was 4½ inches in diameter, and was divided to 0’05 of an inch. Its scale ranged from 31 to 17 inches, and it weighed, when in its leather sling case, 2½ lbs. It was made by Mr. J.J. Hicks, 8, Hatton Garden. Aneroids of this type will be called Watkin’s Mountain Aneroids, as they are especially devised for mountain travellers, and for survey work amongst mountains.

I am, Sir, your obedient Servant,

Edward Whymper